Open Science Repository Business Administration

doi: 10.7392/Research.70081930

Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm

Alma Lilia Sapién Aguilar, Laura Cristina Piñón Howlet, María del Carmen Gutiérrez Diez, Marisela Sáenz Flores

Faculty of Accounting and Administration of the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Mexico

Abstract

Training is currently not understood by medium-sized Mexican firms as an investment that helps businesses to succeed. The aim of this study was to analyze training in such firms. The methodological approach was non-experimental, or ex post facto, and exploratory and descriptive. The Mexican Business Information System was consulted and medium-sized industrial companies were randomly selected. The results indicate that decisive actions need to be taken so that training to be no longer viewed by medium-sized Mexican firms as a needless expense, but rather as the best investment made in Human Resources. Therefore, training must become part of the work culture for all organizations.

Keywords: training, medium-sized companies, work culture.

Citation: Sapién-Aguilar, A. L., Piñón-Howlet, L. C., Gutiérrez-Diez, M. del C., & Sáenz-Flores, M. (2013). Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm. Open Science Repository Business Administration, Online(open-access), e70081930. doi:10.7392/Research.70081930

Received: January 22, 2013

Published: February 18, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Aguilar, A. L. S., Howlet, L. C. P., Diez, M. del C. G., & Flores, M. S. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Contact: [email protected]

Introduction

Training is a form of education through which individuals acquire knowledge, abilities and skills that are necessary to achieve efficacy and excellence in carrying out tasks, functions and responsibilities. Specifically, training is an educational process, strategic in character and applied in an organized and systematic manner, that modifies attitudes (William, 1993). The new work culture seeks to encourage ongoing training of workers and entrepreneurs (Amitabh and Manjari, 2004) to improve the level of life of individuals and at the same time optimize the performance quality of organizations, bringing benefits to both in the process (Vázquez, 1997). Yang and Yang (2010) noted that the majority of private firms in China give little attention to providing training programs, which is a common problem for almost all firms.

Development should consider the person integrally (Rubio, 2004), that is, it should consider the full formation of the personality, character, habits, education on civic participation, cultivation of intelligence, sensitivity toward human problems and the capacity to lead. In other words, it is a process to accentuate or acquire values, styles, teamwork and other facets of the personality (Arias and Heredia, 2010). To use the terminology of traditional logic, if we consider the genus to be education, then the species would be training. The outcome being sought and envisaged is the psychological, social, technological and economic development of individuals, groups, organizations and countries (Rodríguez and Ramírez, 1991).

Despite the great importance of small and medium-sized firms in Mexico, these firms barely have up-to-date and dynamic training programs. Also, it should be noted that, in general, training programs have not been a central demand of unions (Sánchez-Castañeda, 2010). It is clear that training should be considered as a fundamental instrument of the public policies of a country to ensure the workers can gain and maintain employment and adapt themselves to activities in the event of losing employment. As well as being a support to worker employability, training is an economic instrument that improves the productivity-competitiveness of firms (Sánchez-Castañeda, 2010).

The current tendencies that determine the behavior of firms are being configured in the context of globalization and technological advances. A significant part of the competitive economic advantages lies in the knowledge, skills, abilities and capacities of the labor force (Vázquez, 1997). Nevertheless, there are few training and staff development programs in Mexico. One of the tasks of human resource management is to provide the training required by the job position or by the organization. Given the above, the objective of this study was to analyze training in 17 medium-sized firms in the industrial sector in the city of Chihuahua, Chihuahua State, Mexico, to identify the way in which training needs are determined. A second objective was to determine if training is systematic and conducted in a timely manner and in appropriate circumstances and specifying the targets of these programs. Recognizing the relevance of training and development to introduce a change in attitudes and conducts that promote the creation of a working culture can result in increase in productivity and competitiveness of workers and firms.

Materials and methods

This study is in the field of social science is of an exploratory type, given that the objective was to examine a theme that has not been well studied. It can be classified as descriptive because it involves the description, recording, analysis and interpretation of the current nature, composition and processes related to training in medium-sized Mexican firms (Sampieri, et al, 2003). According to the control over the variable, this investigative study corresponds to a non-experimental or ex post facto design, since it observes the situation or phenomenon as it is, in a natural context for subsequent analysis. This research independently measures concepts or variables related to training in firms in the area of study. The universe of the present study is composed of the directors or managers of medium-sized companies in the city of Chihuahua, Chihuahua State, Mexico, in the period from June 2009 to August 2011. As a first step in carrying out this research, the webpage of Mexican Business Information System (Sistema de Información Empresarial Mexicano - SIEM) was consulted and 38 medium-sized firms were identified from the industrial sector in the city of Chihuahua. The 38 companies have between 51 and 250 employees. From among these 38 medium-sized firms, a random sampling of 17 was selected. The selected firms are engaged in providing professional and administrative services, construction in general, roadway construction, preparing concrete, processing corn meal, pasteurization, packaging and distribution of diary products, dealing in and servicing communication equipment, coffee processing, manufacturing metallic dies, metallurgy, the sale and distribution of LP gas, marketing meat products, and the fabrication of doors and moldings. A structured questionnaire, previously validated by experts, was used to gather data. The first contact with the firms was made by telephone with the purpose of giving information about the project and requesting cooperation. Once a firm agreed to participate in the study, we sent the firm the questionnaire by email. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions. Questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 10 and 15 were binomial and the rest were multiple-choice. Before presenting the questions, additional information was sought regarding: the date, the name of the firm, the person completing the questionnaire, his/her position, email and telephone number. Following the application of the questionnaire, a database was developed for subsequent graphing and analysis using descriptive statistics.

Results

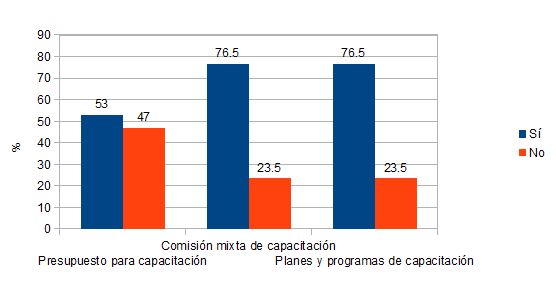

The first question in the questionnaire was: Is there a budget assigned to training? Some 47% of firms indicated that they do not have a budget assigned to this area (Figure 1). This does not mean that firms do not conduct staff training, but rather, according to the training needs, that emerging courses are programmed and the necessary budget is assigned. It is important to note that 53% of the firms do budget for costs associated with training.

Figure 1: Budget, Management-Labor Committee, plans and programs and training areas

The second question in the questionnaire was: Is there a management-labor training committee in the firm that is legally constituted and registered with the Secretary of Labor and Social Security? The middle part of Figure 1 shows that 76.5% of the firms stated that they have management-labor training committees that are legally constituted and registered with the Secretary of Labor and Social Security (STPS). The remaining 23.5% of the firms can be considered high, as it represents nearly a quarter of the interviewed firms.

The third question in the questionnaire was: Does the firm have training plans and programs duly registered with the Secretary of Labor and Social Security? The last two bars in Figure 1 show that 76.5% of the firms stated that they have such plans, while the remaining 23.5% stated that they did not, a high percentage given that it represents a quarter of the interviewed firms.

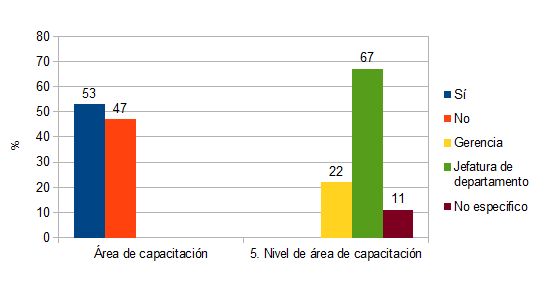

The fourth question was: Is there an area responsible for training in this firm? Some 53% of the firms declared having a specific area responsible for training, while 47% stated that they did not (Figure 2), which could be due to the small size of the firms and the lack of departmentalizing of specific tasks.

Figure 2: Areas and levels of training

The fifth question in the questionnaire was: At what level is the training area located in this firm? The last three bars in Figure 2 show that, in 22% of the interviewed firms, responsibility for training is located at the management level, in 67% at the department chief level and 11% of the firms did not specify.

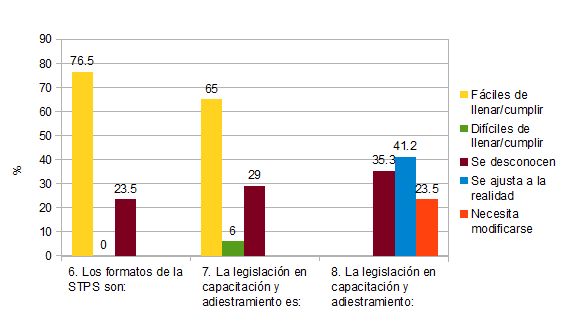

Question six posed the following: The forms required by the Secretariat of Labor and Social Security (STPS) are: easy to complete; difficult to complete; or the firm is not familiar with the forms. Figure 3 shows that 23.5% of the interviewed firms were not familiar with the forms. This percentage is high given it means that these firms have never provided systematic training.

Question seven of the questionnaire asked if the legislation in relation to training is easy to comply with or if the legislation in its details is unknown. The results are shown in the middle part of Figure 3, where it is evident that 32% of the firms are unfamiliar with the legislation on training in its details. This percentage is high given the importance, in particular for those responsible for the human resources area, of being well informed and up-to-date with this legislation.

Figure 3: Forms and legislation on training

Question eight asked if the legislation on training is adjusted to the reality of the country, if it needs to be modified, or if the details of legislation on training are unknown. The last three bars in Figure 3 show that 41.2% of the interviewed firms expressed the view that training-related legislation is adjusted to the reality of the country; 23.5% thought legislation needs to be modified and 35.3% was not familiar with the legislation in this area. This last percentage is alarmingly high, given that it represents more than a third of the interviewed firms.

The ninth question in the questionnaire was: How do you consider training activities? The following possible responses were offered: as a generator of increased productivity; as a generator of increased competitiveness; only to meet legal requirements because non-compliance results in having to pay fines; or as a means to favor personal growth and avoid the obsolescence of the organization. Figure 4 shows that these results were highly positive, given that 53% considered training as a generator of increased productivity, 59% as a generator of increased competitiveness and only 12% as simply a way to comply with legal requirements and avoid paying fines. Some 65% of the firms considered training as a means to favor personal growth and avoid the obsolescence of the firm, while only 6% of the interviewed firms have never engaged in training.

The tenth question was: Is a needs assessment conducted prior to initiating training activities? The great majority of the firms, 76.5%, carries out a needs assessment before initiating training activities (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Incidence of training and the identification of training needs

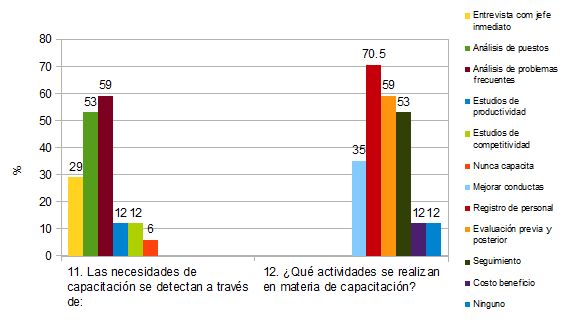

Question eleven asked the following: The assessment of training needs is conducted through: interviews with the respective immediate chiefs; an analysis of the job positions; an analysis of the most common problems; productivity studies; or competitiveness studies. Figure 5 shows that 53% of the firms use analysis of positions and 59% use analysis of the most common problems to plan training programs, while only 12% use productivity studies and 12% competitively studies. This indicates that contents of these plans and programs responds to classic activities and trades.

Question twelve was: Which of these training activities does the firm carry out? The following options were offered: behavior objectives are established to be achieved through training; staff records are established indicating the level of knowledge and abilities of each worker; staff evaluations are made before and after training; follow-up to training is conducted; and cost-benefit indices of training are registered. The last six bars in Figure 5 show that 70.5% of the firms have records of trained staff, 59% conduct evaluations before and after training, 53% do follow-up to training. Nevertheless, two of the most important activities had low percentages: establishing behavioral objectives, with 35.3% (which should be viewed as very low considering that one of the purposes of training is to modify conduct), and making a record of the costs-benefits of training, with only 12% of the interviewed firms. It should be noted that this is one of the main reasons that firms do not carry out systematic training.

Figure 5. Needs assessment and training activities

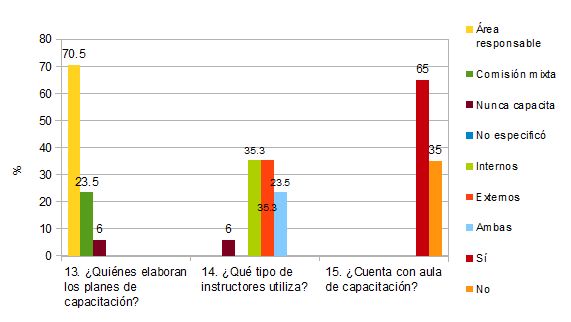

Question thirteen was: Who develops training plans? Two options were given: the area responsible and the area involved or the management-labor training committee. Figure 6 shows that in 70.5% of the firms the area responsible and the area involved develop training plans, followed by the staff that make up the Management-Labor Training Committee with 23.5%. This result can be described as positive, suggesting that the courses that are provided are appropriate, although it does not imply that training is integral to the firm.

Question fourteen was: What kind of instructors do you use more often, internal or external? As shown in the middle part of Figure 6, internal and external instructors are used with the same frequency.

Figure 6: Training plans, instructors and training spaces and classrooms

Question fifteen asked: Does the firm have its own training classrooms? The fact that 65% of the firms have their own classroom spaces indicates the level of good intention. The preceding brings important benefits such as reducing training costs and avoiding that staff have to leave the workplace, which would involve, among other things, a saving in staff time (Figure 6).

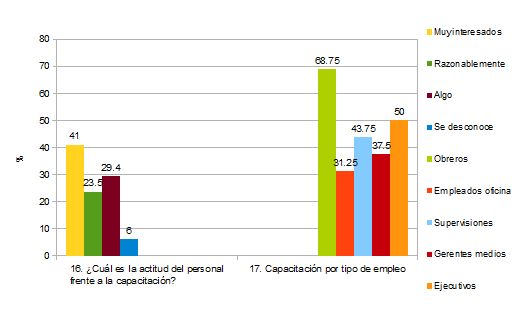

Question sixteen was: What is the attitude of your employees towards training, reasonably interested or somewhat interested? The results from this question are not very positive, given that at 50% of staff should be very interested in receiving training. In 6%, nothing was known about employee attitudes toward training, which is because these firms have never provided training (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Attitude of staff toward training and training by the type of employment

Question 17 asked respondents to indicate the employment types that training is directed at, using a descending scale from five to one, representing the most common target for training to the least, using the categories: laborers, office workers, supervisors, middle-level managers and executives. Figure 7 shows that 68.75% of the interviewed firms responded that the main target of training is at the laborer level, and 31.25% and 43.75%, respectively, at the levels of office workers and supervisors. Some 37.5% of the firms direct training at middle-level managers after giving priority to three aforementioned groups. Finally, 50% of the firms responded that the group that is targeted least for training is executives.

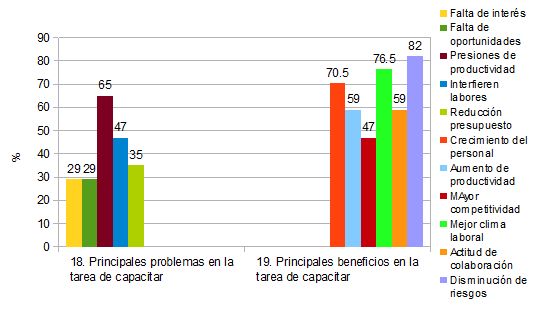

Question 18 in the questionnaire was: What are the main problems faced in this firm in the task of staff training? The following options were offered as responses: lack of interest by the staff; productive pressures that impede dedicating time; training is viewed as interfering daily work; sufficient opportunities for improvement are not offered to staff that have already received training; courses are often not adjusted to the real needs of the firm; lack of effective trainers; lack of adaptation of the courses to the Mexican content; the paperwork that must be done with government authorities represent the investment of much staff time; difficulties to complete application formats; and reduction of the budget assigned to training. Figure 8 shows that the lack of interest on the part of the staff as one of the main problems in conducting training, which coincides with the problem of lack of opportunities for improvement for staff that have already received training, both with 29%, the pressures of productivity 65%, and seeing training as an interference with daily work 47%, representing the highest percentages, which is paradoxical. The 35% that identified the budget reduction assigned to training shows that this is one of the main activities affected by the decreased resources.

Figure 8: Main problems and benefits associated with training

Question 19 was: What have been the main benefits from staff training? The following options were presented: personal growth; increased productivity; greater competitiveness; improved working climate; cooperative attitude generated; and decreased risks of injury in the workplace. The main achievements or benefits obtained from training appear to be more ideal than real, with 82% identifying reducing workplace risks, which may be due to the industrial nature of the sector, where workplace risks imply high costs. The percentage that referred to increased productivity is closely related to the attitude of collaboration generated, both with 59%, and finally, achieving greater productivity with 47% (Figure 8).

Finally, question 20 of the questionnaire was: What do you consider the determining factor for the competitiveness of the firm: capital, technology or human resources? Although it was hoped that the percentage would be higher, it was encouraging that the great majority of firms interviewed considered human resources as the determining factor for the competitiveness of the firm, with 70.5%; another 23.5% identified both human resources and technology, and only 6% responded that capital is as important as the human and technological factors.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, we can say that, while it is certain that there are firms that are making important efforts to train their employees, there is still much to be done. The panorama has not changed significantly in decades. Private sector firms still need to be more conscious of the importance of having systematic training plans and programs in accordance with the demands of this epoch of continuous change.

Currently, what the country requires for the labor sector is to carry out urgent actions to encourage the productivity of labor relations, and boost the economic competitiveness of the country in general. Training is one of the ways in which the right to education is updated within a system of standards that protects work and workers.

The effective use of the human resources of an organization depends on the correct application of the phases of training: to determine training needs; identify the resources for training; design the training plan; execution of the training programs; and evaluation and follow-up.

References

1. Amitabh, K., y Manjari, S. 2004. Towards Effective Training and Development in Indian Public Sector Enterprises: A Case-based Analysis. South Asian Journal of Management. AMDISA Secretariat. 2004. FIND ONLINE

2. Arias Galicia, Fernando

(2010), Administración de Recursos Humanos, 13ª. Reimpresión,

México, Trillas.

3. Arias Galicia, Fernando y

Heredia Espinosa, Víctor (2006, reimp. 2010), Administración de

Recursos Humanos para el alto desempeño, México, Trillas.

4. Ayala Villegas, Sabino

(2004), Texto Universitario, primera edición, Universidad Nacional

de San Martín-Tarapoto, Facultad de Ciencias Administrativas,

Financieras y Contables, Ciudad Universitaria-Morales-San Martín.

5. CEPAL. (2002). Las pequeñas y medianas empresas industriales en América Latina y el Caribe. FIND ONLINE

6. Granell, E. (1994).

Recursos humanos y competitividad en organizaciones Venezolanas.

Ediciones IESCA, C.A. Venezolana.

7. Rodríguez Estrada, Mauro

y Ramírez Buendía, Patricia (1991), Administración de la

Capacitación, serie Capacitación efectiva, México, McGraw Hill.

8. Rubio, A.H. 2003.

Filosofía y Ciencia; desarrollo tecnológico. Chihuahua, México.

9. Sánchez-Castañeda, Alfredo (2010), La Capacitación y el adiestramiento en México, regulación, realidad y retos. Revista Latinoamericana de Derecho Social, Número 5. FIND ONLINE

10. Sampieri, R.; Fernandez,

C.; Baptista, P. (2003). Metodología de la investigación. Tercera

Edición. Editorial Mc Graw Hill/Interamericana Editores, S.A. de C.V

México.

11. Siliceo Aguilar Alfonso

(2004), Capacitación y Desarrollo de Personal, México, Cuarta

Edición, Editoral Limusa S.A de C.V.

12. Vázquez Garatachea, Enrique (1997), Propuesta de instauración de un sistema de capacitación al interior de la empresa en México. Revista Gestión y Estrategia. No. 11-12 número doble, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Unidad Azcapotzalco, pp. 157-164.FIND ONLINE

13. William, B.R. 1993. Enterprise support systems: training and aiding people to plan and manage. Industrial Management. Institute of Industrial Engineers, Inc. (IIE). 1993. FIND ONLINE

14. Yang, H., Yang, X. 2010. Research on enhancing the effectiveness of staff-training in private enterprise. Report. Business. Scientific Research Publishing, Inc. 2010. FIND ONLINE

Cite this paper

APA

Sapién-Aguilar, A. L., Piñón-Howlet, L. C., Gutiérrez-Diez, M. del C., & Sáenz-Flores, M. (2013). Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm. Open Science Repository Business Administration, Online(open-access), e70081930. doi:10.7392/Research.70081930

MLA

Sapién-Aguilar, Alma Lilia et al. “Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm.” Open Science Repository Business Administration Online.open-access (2013): e70081930. Web. 18 Feb. 2013.

Chicago

Sapién-Aguilar, Alma Lilia, Laura Cristina Piñón-Howlet, María del Carmen Gutiérrez-Diez, and Marisela Sáenz-Flores. “Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm.” Open Science Repository Business Administration Online, no. open-access (February 18, 2013): e70081930. http://www.open-science-repository.com/training-in-the-medium-sized-mexican-firm.html.

Harvard

Sapién-Aguilar, A.L. et al., 2013. Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm. Open Science Repository Business Administration, Online(open-access), p.e70081930. Available at: http://www.open-science-repository.com/training-in-the-medium-sized-mexican-firm.html.

Science

1. A. L. Sapién-Aguilar, L. C. Piñón-Howlet, M. del C. Gutiérrez-Diez, M. Sáenz-Flores, Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm, Open Science Repository Business Administration Online, e70081930 (2013).

Nature

1. Sapién-Aguilar, A. L., Piñón-Howlet, L. C., Gutiérrez-Diez, M. del C. & Sáenz-Flores, M. Training in the Medium-Sized Mexican Firm. Open Science Repository Business Administration Online, e70081930 (2013).

doi

Research registered in the DOI resolution system as: 10.7392/Research.70081930.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.