Open Science Repository Architecture

doi: 10.7392/Architecture.70081915

Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences

Messaoud Aiche, Mohammed Derradji

Department of Architecture of the University of Constantine, Algeria

Abstract

The present paper debates the "communication" aspect in the apprenticeship of the architectural project. Firstly, we explain the meaning of the term "competence" that we borrow from education sciences. Then we expose the communication competences necessary for the practice of the project according to the points of view of the authors interested by the matter. These competences should be the object of apprenticeship in architectural education, though that is not the case in several schools of architecture. In a second part, we present the results of the investigation analysis of teaching practices implemented for the teaching of the fifth year projects (final project) at the department of architecture of the University of Constantine, Algeria. This analysis has confirmed that these practices do not permit to develop all communication competences of students and, consequently, do not prepare enough the future architect to impose himself as a proposal force facing different actors of the project. This confirms in fact our concerns about the apprenticeship of the project of architecture regarding communication aspects.

Keywords: pedagogy, architectural project, competence, communication, actor.

Citation: Aiche, M., & Derradji, M. (2012). Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences. Open Science Repository Architecture, Online(open-access), e70081915. doi:10.7392/Architecture.70081915

Received: November 30, 2012

Published: December 28, 2012

Copyright: © 2012 M. Aiche & M. Derrradji. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Contact: [email protected]

Introduction

The interest that we confer to teaching competences of the project of architecture in its communication aspect is motivated by a preoccupation concerning the efficiency of the educational practices, which do not seem to achieve the expected effects. In the practice of architecture, the authors agree on the necessity of communication competences of the architect in the design process. Paradoxically, these competences are not enough taken as a problematical object of apprenticeship in architectural education, despite their importance. This leads to ask questions on the educational practices implemented with respect to the apprenticeship of communication and the capacity of these practices to forge communicative competences, allowing the architect to impose himself as a proposal force facing different actors.

In fact, if the term project is complex and combine, at the same time, the process, the competences (of conception and of communication) and the result (real or simulated), it is remarkable to note that its teaching seems to be nowadays predominated by ambiguous and arbitrary methods of teaching and evaluation criteria [1]. Although the present work does not have the intention of exploring the complexity of the project, it has, on the other hand, the ambition to put in epigraph the "communication" aspect in practice and apprenticeship practices. (The project here is undertaken as an educational exercise and not as a real project). Before we enter into the lively of the subject, it is worthy first of all to define the term competence. What is then a competence?

The usage of the term competence is very frequent in the objectives of teaching methods of disciplines that prepare to some practice. The principal goal is "to forge necessary competences to the exercise and go forward and unstop to carry out a job, […]. Theses achievements recover all knowledge, know-how and interpersonal skills of which an individual can hold in a professional, social or formation activity" [2]. In education, a competence represents "The position identifiable, reparable and measurable that corresponds to a task that the student will be able to resolve in an effective way" [3]. In the accomplishment of this task, the student has, therefore, to manifest a knowledge, skill and knowledge to be.

Seeking competences is the principal object of the apprenticeship in the active methods of learning. Such approaches intend to surpass a theory by strictly behaviorist objectives, which stipulates that the specific and observable production of a behavior is the indicator of apprenticeship, by a theory which puts questions on the object of apprenticeship, i.e. what the learner has to develop or acquire: competences. This is as in architecture, for example, we must distinguish between to learn to draw (a behavior) and to learn to communicate the characteristics of a space by the drawing (a competence). In the latter case, it is a matter of accomplishing a task.

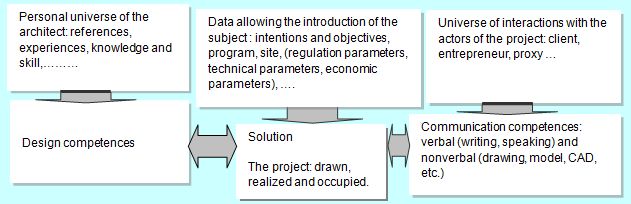

The communication, an essential competence in the apprenticeship and practice of design

In the tradition of teaching architecture, the student is invited, during the different steps of apprenticeship, to elucidate his project through different means of communication. No matter if the communication is verbal: wording of the problematical situation, compilation of the memory, reports of research, oral bill-posting etc.; no matter if it is nonverbal: the render consisting of the different representation graphics (drawings in two and three dimensions, models, photos, pictures, etc.). The student is called, therefore, to make use of the verbal and nonverbal communication throughout the different steps of apprenticeship. Paradoxically, the educational reality tells us that there are no lessons or criteria of evaluation previously given to the students on the question of communication (especially in the matter of the verbal aspects), despite its importance. This knowledge is considered as a matter which the student is strained to learn by himself. In practice (professional life), the project must satisfy not only the designer (the architect), but all parties concerned (customer, corporation in a general way, contractor, decision-maker, mandatory etc.). The project takes forms in a sort of complex negotiations between different actors, from the decision of the customer to construct a project until its realization. The activity of the architectural project integrates, therefore, the personal universe of the architect and the universe of interactions with other actors, acquired by the architect communicative competences. Figure 1 shows the importance of communication in the design process.

Fig. 1: Architect activity taking place in two universes

J.P. Boutinet asserts that "any project following the example of any drawing accomplishes… two functions: it materializes the idea…, it communicates the idea to others" [4]. J.P. Epron, puts in epigraph the communicative dimension of the project and testifies that "The architectural project is a social act, a fact which concerns lot of actors, this is a shared act and it must not be reduced at the only work of the architect and his team" [5]. A. Bendeddouch, after studying the different interpretations of the notion of the project by different authors, through the extension of the museum of Montreal, glimpses the term "project" in a triple dimension: the design, the drawing that she considers also as means of communication and the real building [6]. Communication between different actors takes place according to several forms: verbal (records, correspondences, reports of visits to work-sites, meetings, exchange of correspondences…) and nonverbal (sketches, drawings, outlines, study models, pictures, films, etc.). Therefore, to every phase corresponds a type of representation.

Communication competences in the apprenticeship of the design process

Before that the design of the project and its coming into being were considered as two distinct operations, communication between the architect and other actors was undertaken on the work-site with a process of "attempts and errors" following progressively the realization steps of the project [7]. The usage of the project to communicate the characteristics of the construction climbs back up to the end of the fifteenth century. The projects were, therefore, stimulating hypothetical exercises in reference to the reality of the practice and of what will be the future building. In the practice of the architecture, the usage of the project as an imagined edifice once for all, in replacement of a progressively transformed construction, constitutes a redefinition of the role of the architect. The latter is considered as an artist that will have the art and the manner to imagine the building in its least details before its realization. These details are communicable to those that will execute it (contractors) through drawings (plans, cut elevations…). They allow at the same time the architect to carry out an a posteriori checking of the accordance of the realizations with the established plans. Meanwhile, the act of conception (design) has become complex and then it is has been noticed that between the design of the project and its realization there is a very complex system of information and points of view exchange (discussions, negotiations, meetings, expositions, information exchange, etc.) from and to the architect and different actors. This situation leads to a reconsideration of communication in the apprenticeship of architecture, taking into account verbal aspects (written and spoken) and nonverbal aspects (drawings, pictures, models, etc.).

In teaching design process, we have always given little importance to theses aspects. They are rarely the explicit, methodical and progressive object of apprenticeship. Nevertheless, to every moment of the apprenticeship of the project, we invite students to explain their projects by the usage of different means (writing and speaking). The usage of the verb in the project is not to be discussed for the reasons that we have just evoked and should be acquired with drawing skills [8]. This lack of the verbal communication skill is clearly felt through the written documents and during the presentation of diploma projects, where we can note that the majority of the students express themselves with unclear expressions. In fact, speeches undertaken (written and spoken) are not presented in a clear way, as the ideas and intellectual fundamentals having guided their works. Therefore, many presented projects lose a bigger party of their fuel and substance. In practice, this can lead inevitably to failure. Nevertheless, the architecture is a shared language with which apprenticeship goes through, and failing in the acquisition of this language condemns the student to stammer eternally.

It is, therefore, remarkable to note that little interest is attributed to the teaching of these aspects in architectural studies, either in the form of a support subjects to the project or being part of its apprenticeship. This situation has lead for a long time to the consideration of drawing as the unique mean of communication in the teaching design process (between student and teacher) or in practice (between the architect and other actors) [9]. Despite all the reforms of architectural studies, we realize that very few interest is allocated to the communication as an object of apprenticeship, in spite of its presence through the design process and all exchanges between teachers and their students, between architects and other actors of the project. The question is to know if we continue to consider it as implicit knowledge that the learner acquire by his own effort. The absence of a true description of the problem hides an essential part of the apprenticeship of the project and contributes to the weakening of the competences of the future architect facing other actors. It is certain that taking in charge the verbal communication is to be looked for in teachings support courses to the project and in the teaching of the project itself. In the latter case, the problematical elaboration can be done at three levels:

1. The wording of the problem

The wording of the problem, that consists of putting right questions around the subject that we want to deal with, goes through taking into account actual data about the problem (intention, program, economical factors, statutory parameters, etc.). The information collected can be done by the investigation organized in situ in the form of direct discussions with the actors of the project (customers, users, decision-makers, etc.), or by the questionnaire, visits to the sites, etc. These activities allow the students to express, argue, listen and understand the representations that have other actors on the question treated. The importance of this first phase is the comprehension and the construction of the subject that allows apprehending the purpose of the project, before passing to its drawing. It allows the student to develop its relational competences. At the end, the student is able to produce a sort of document in the form of a notebook consisting of: the questions that he asks about the subject and to which he will find responses, the objectives aimed by the project (which he wants to attain through the project), as well as the analysis of the whole data of the project (programs, site, parameters - economical, technical, statutory), that is to say, the conditions in which the project will takes form.

2. Written wording of the speech accompanying the solution

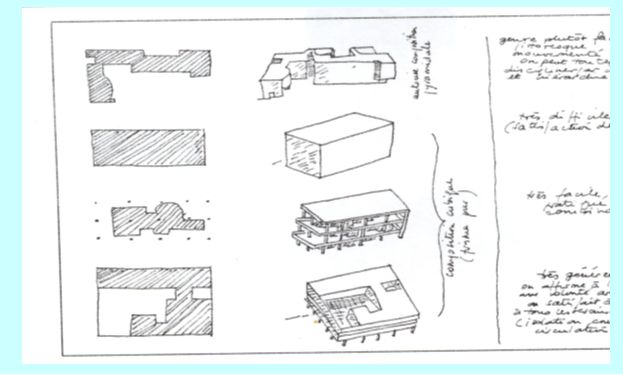

The speech that accompanies the work is developed alongside the drawing output. During the reflection, the architect produces drawings that he comments on with small sentences. This can be noted throw sketches of celebrate architects (figure 2), such as C.J. Le Corbusier, quoted by P. Boudon (1994) [10].

Fig. 2: The speech accompanying sketches. La villa Garches de Le Corbusier

At the end of apprenticeship, the drawn project should be accompanied by a document consisting of the architectural speech. In this document, the student must be able to explain and to properly argue the ideas that have founded his project. He expresses his point of view by words to link up the thinking to the production [11] and unveil what the drawings cannot reveal. If the architect produces speeches during the whole process of the design, the apprenticeship has, therefore, to allow the student to obtain necessary competences to the production of these speeches. The teacher must then make sure that any presented document is capable to do the faithful interpretation of ideas contained in the different drawings.

3. The wording of the oral speech accompanying the solution

During the research of the solution, and at different corrections, teachers must observe whether the student uses in his expression (explanation) a fitted technical language. Part of the corrections will concern these aspects. At the end of apprenticeship, the student should be able to plead for his project. It is obvious to note that taking into account the verbal communication aspect goes through its problematical elaboration, during the different moments of the design process. This is possible by:

- The organization of apprenticeship situations inciting students to build their works in the form of a written document, accompanying the graphic documents, during and at the end of every moment of apprenticeship

- The organization of debates allowing the members of the group to express themselves and to exchange their point of view

- The exhortation for the students to establish by themselves questionnaires, observations, letters for visits, etc.

- The effective evaluation of these activities as competences to acquire.

The means allowing the achievement of these competences are numerous. They can be elaborated as apprenticeship positions or as part of the exercise of the project. Nevertheless, they must lead to measurable and assessable productions (documents, etc.).

The nonverbal communication in the apprenticeship of the project

This aspect of communication is the most emphasized as a problem in the apprenticeship of the project, often in the form of representation of space. This allows the designer to communicate first with himself (design thinking), that is to say, to externalize the solution contained in his imaginary and to make it perceptible and intelligible [12], and after that with the other actors. The principal objective of the nonverbal communication is the simulation of the real space, i.e. the communication with much precision and fidelity of the characteristics (plastic, technical, etc.) of the space, so as to give rise to a reaction (positive or negative) from the customer concerning the space where he wishes to organize his activities. In architectural education, the nonverbal communication constitutes the main support of the relationship between students and teachers. In practice, it is the main support of interactions with the actors of the project. The nonverbal communication in the apprenticeship process should, therefore, be taught, in order to produce feedback (the reaction of other actors). It can be achieved by different means: the drawing in all its forms (outlines, sketches, technical drawing in two and three dimensions), the model (the model), and the computer-assisted drawing (DAO).

1. The drawing

The tradition of the drawing in architecture appears during the nineteenth century as specificity of the work of architects [13]. It was considered the means to learn architectural design, which will be perfected during that century by the school of “beaux arts” (France). The specificity of the drawing of architecture, compared to other drawings, comes from the fact that it includes the human being (which penetrates, walks, lives…), in contrast to painting or sculpture, whose representations ignore the real human being [14]. Several studies underline the importance of drawings as means of communication and support of mediation and negotiation between architects and other actors. These studies showed that to every moment of the process corresponds a drawing type, i.e. to a communication technique. In this context, M. Conan [15], referring to William Kirby Lokard, assimilates the design process to an obstacle journey. To every step of the journey corresponds a drawing type that filled a function in the design process. He thus distinguishes:

- Drawings for exploration of the problem such as diagrams, outlines, matrix, etc. The goal of these drawings is to transform the problem in graphic representations

- Drawings used to clarify the different points of view of the actors after consultation, which allows the architect to modify his point of view and establishes synthesis of the different aspects of the treated problem (outlines, sketches …)

- Elaboration drawings, of which the goal is to explore partial solutions and specific parts of the problem

- Perlaboration drawings that allow following the examination of the problem from several alternatives; this allows making obvious all aspects of the problem (technical drawings, details to fitting scales)

- Execution drawings intended for different actors (administrations, contractors, engineers…)

- Exposition drawings as simulation of the space after achievement of the building.

Inspired by cognitive studies of J. Piaget, while observing the activity of the architect during the design process, Lebahar C. concludes that the drawing is a mean of expression of the intelligence of the architect during the design process [16]. He argues that, in the design process, the architect is involved in a process of elimination of the uncertainties, while wearing that to every phase of the process corresponds a type of drawing. The final drawing corresponds to the elimination of the uncertainties and to the maturation of the solution. This process is composed of three phases corresponding to three forms of representation [17]:

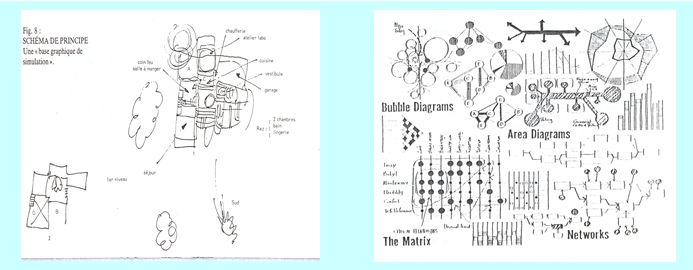

- Drawings allowing representation of the problem and of establishment of the graphic basis of simulation: it is a matter of a representation of the problem and of a selection of information, spatially being able to be represented (the non-spatial descriptors, like the number of persons, and spatial, like a terrace in a precise place). The used means are photographs, sketches, etc. This allows to establish the graphic basis of simulation (the reduction of the space to the drawing table) and constitutes, in fact, a first response (uncertainty reduction) for the representation of the problem

- Graphic simulation drawings (research of the object phase), the designer is deeply implicated in the research of the solution (reduction and elimination of uncertainty to attain the degree zero). The architect "builds and destroys places, moves partitions… lengthens and shrinks terraces" [18]. Sketches clarify all the parts of the project with drawings in two and three dimensions

- Model construction drawings (establishment of the documents to execute the project); this constitutes the precise graphic documents, drawn to a precise scale and allowing the realization of the project

We can conclude that the quest of the solution to a problem is achieved through different moments where the architect is invited to produce different types of drawings. To every moment corresponds a drawing type, this includes:

a) Drawings used to explore, understand and represent the problem (outlines, sketches, diagrams, photos…); this allows the graphic construction of the subject (figure 3).

Fig. 3: Base graphic of the problem and exploration

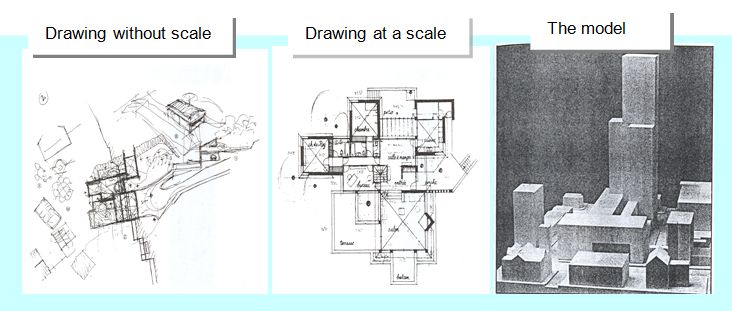

b) Drawings used to elaborate the solution (graphic simulation in 2 and 3 dimensions to fitting scale or without a scale, study model, etc…): figure 4.

Fig. 4: Drawings for solution elaboration

c) Drawings as simulation of the space in which the content depends on their destination (public consultation, expositions, publications…): figure 5.

Fig. 5: Drawing for reality simulation

The usage of the drawing in three dimensions allows a better simulation of the reality. This last one is apprehended through a multitude of points and successive movements in and around the object. This (fourth dimension) constitutes for the architect "the moment that allows the distinction between constructed and drawn space" [19].

d) Drawings used to execute the project; destined to different actors: figure 6.

Fig. 6: Executing drawing

The teaching of the project should allow the student to explore all these drawings through the different moments of the process of apprenticeship. This makes the architect capable to communicate by the most fitting means.

2. The model

The model usually represents the reduced copy of a project. It was considered as the most privileged representation method in the "Bauhaus" (Germany) teachings besides of axonometric design. For certain authors, the model plays a crucial role as means of communication between the architect and the customer during the phase of representation and comprehension of the problem, as well as during the presentation of sketches [20]. Models allow lighting up the customer on the project between an initial state and a future state, and show the relationship that can be established between existing buildings and new elements. In the apprenticeship process, the usage of the model, during the construction of the subject and during the research of the solution, is certainly important. It allows appreciating the initial state of buildings that form the context in which the new project will be inserted. They also permit to perceive the future state of the space and relationship that will be established between its different elements. Experience in teaching architecture showed that the model allows students which do not dispose of enough drawing skills to express their ideas by the possibility of moving elements of the project, adding and suppressing parts, etc. The usage of the model permits also to realize and to illuminate details of construction that are difficult to explain by drawing. It is, therefore, clear that the model is a mean of communication which the architect is called to use through the different phases of the elaboration of the project. The apprenticeship should allow students to go over the different manners of its usage.

3. The aided computer drawing (A. C. D)

The generalization of the use of the computer, since 1980, produced huge transformations in the practice and teaching of the architecture. Regarding communication, the introduction of the computer has been achieved by several manners:

- The computer-assisted drawing, as a communication tool in replacement of the conventional drawing: This represents a transposition of the table of drawing towards the screen. The students use software programs to represent their projects to produce better qualities of spaces than they conceive. This includes pictures, treatments, drawings, animated programs (3D). These new techniques of communications continue to seduce architects and their customers, and require a perfect knowledge of software programs. The usage of computer has been generalized in professional life very quickly and very excessively, tending to substitute the conventional way of representation.

- Analysis and simulation programs applied to projects: This includes all software programs in relation to lighting, acoustics, structure and energy building. These software programs are conceived to allow improvement of buildings performances.

- The virtual space exchanges through the web: They are conceived to allow the realization of the project while exchanging the news among actors through the internet (even out of the working hours). This permits good flexibility of the work and a huge saving of time.

It is, therefore, clear that the emphasis of the communication (verbal and not verbal) as a problem of apprenticeship seems to be an indisputable necessity and an essential competence to practicing architectural design. The latter depends enormously on the quality of interactions between different actors engaged in the same project.

Analysis of educational practices of communication apprenticeship

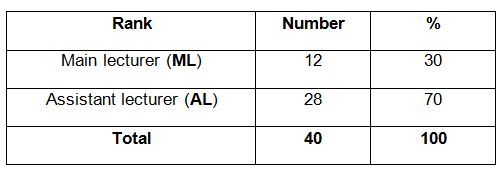

In this section we present the analysis and interpretation of the investigation results of the educational practices of communication apprenticeship aspects in the department of architecture in Constantine, Algeria. The investigation encompassed a population of 40 teachers (of which 12 main lecturers and 28 assistant lecturers) having taught the project of the fifth year students (final projects) between 5 and 19 years. Concerning the investigation process, we used the questionnaire as a technique for the collection of the primary data of the study. The exploitation of the mass of information needed the use of the statistic software called SPSS. After a coding system, the treatment of the raw data allowed establishing easily exploitable panels. The analysis level that allows these panels is the "cross tabulation", of which the objective is the correlation between two variables: a statute variable (rank, number of taught years) and a nominal variable (a question). The manipulation of the variable "rank" (main lecturer, assistant lecturer) permits to verify the effect that could have this variable on the nominal variable. For this variable, the studied population is composed of two groups of teachers as follows:

Table 1: Rank of teachers

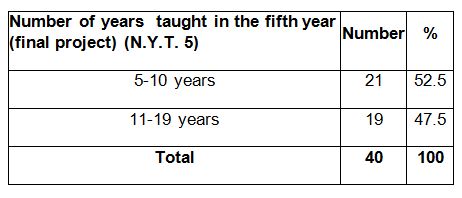

The manipulation of the variable "number of years taught in the fifth year (N.Y.T. 5) has for objective to verify the effect that could have experience in the teaching of the fifth year (final project) on the nominal variable (a question). For this variable, we have identified two groups of teachers as follows:

Table 2: Experience in teaching

To find fitting keys of interpretation to the types of the data collected, we present the most significant results through histograms in relation to the panels pre-established. This allows direct analysis and interpretations. In order to better measure the content we present, a first reading of the tendencies of all the responses to each of the questions contained in the questionnaire was performed. This certainly facilitates the comprehension of the educational practices of teachers. In a second time, the crossing of the statute and nominal variables through their corresponding indices [21] was used. Every indices (or axis of the questionnaire) is presented in the form of a graph accompanied by a list of data (criteria designated by the letters C1, C2... C9), considering the different variables (rank: ML/AL and number of years taught in fifth year: N.Y.T.5). The comparison of the different graphs allows describing and understanding the difference (if there is one) of teacher behavior regarding the rank and the number of years taught in the fifth year (i.e. the final project).

The apprenticeship of communication does not allow simulating the real space and grants little interest to the verbal aspect

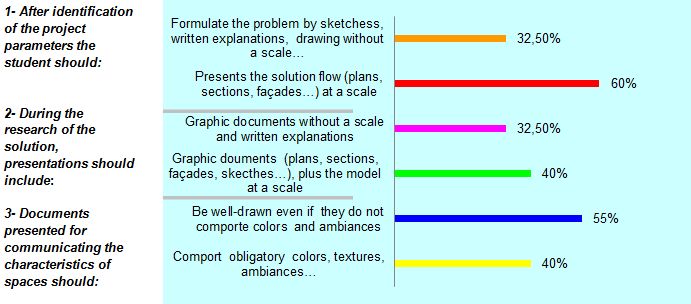

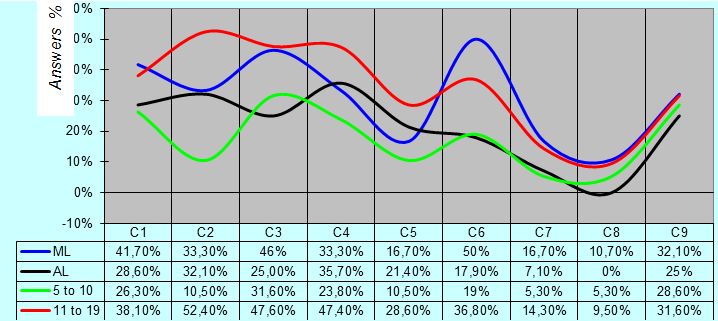

In the practice of architecture, the notion of project engages several actors. It sends back, therefore, to an exchange system between the architect and other actors, using appropriate communication codes: verbal tools (manuscripts and speeches) and nonverbal tools (drawings, models, photos..). The handling of these means, by the architect, allows the project to be accepted and executed [22]. In the apprenticeship process, it is imperative to ask the student, during the different steps of apprenticeship, to communicate his design through the different means of communication (a competence to develop). These means should evolve along with the evolution of the design process, i.e. from the exploration of the problem (outlines, explanations...) to the final presentation (drawings to a scale, images…). In this part we aim to verify if the apprenticeship practices aims the acquisition of all the competences of communication. The figure 7 shows that:

- No more than 32.5% of the teachers take into account the sketches and written matters that allow exploring and understanding the problem. The majority (60%) forces the student to present the solution throw drawings to a scale. The communication is, therefore, perceived under the angle of the drawing to a given scale.

Fig. 7: Work presentation

During the research of the solution (figure 7) few interest is given to sketches and written explanations (32,5%). Representation (plans, cut, models...) to a scale is the favorite means of communication (40%).

During the presentation of the solution (figure 7), the usage of color and moods is important to illustrate to the customer the characteristics of the space. We obviously appreciate better a space with its colors and moods. The results show that only (40%) of the teachers persuade the students to make use of colors and moods, while (55%) are satisfied with well-drawn documents without colors and moods. This last category of teachers takes into consideration only a small part of the actors, those responsible for the realization of the project.

The usage of the computer in the design process can be done by several ways. In apprenticeship it cannot be reduced to a simple improvement of the quality of drawing skills. It is a matter to explore other methods that allow improving the communication quality. On the figure 8, we paradoxically note that the majority of the teachers (65%) believe that a computer serves to improve the quality of representation. The communication aspect is far to constitute the principal preoccupation. For proof, in only (35%) of cases, the computer serves to the simulation of the reality that is related to other actors.

The usage of the model in the design process as a means of communication besides the drawing is multiple; it must not be limited to final simulation of the solution. During the phase of comprehension of the problem, it allows feeling the state of the places (site, disposals of constructions that form the context in which the new project will be inserted …). During the research of the solution, the model allows those who do not have enough skills in drawing a better possibility to express their ideas, by the offered possibilities of movement of the elements, addition and suppression of parts and elements, etc. Figure 8 indicates that the usage of the model serves especially to the intermediary presentation (the sketch, 47.5%) or final presentation (50%). Few interest is attributed to the usage of the model at the comprehension of the problem phase (7,5%) and during the research of the solution (10%), which explains the scarce consideration directed to its use during interactions with the other actors of the project. This seems to be intense [23] before even the establishment of the final solution. From the educational point of view, this approach diminishes the value of the model as alternate to the drawing and participates in the weakening of the communication competences of learners.

In the apprenticeship of the design process, the selection of the fitting tools of communication must not be decided by the teacher alone. The learner must be, as most as possible, implicated in the selection of these means. The teacher becomes advisor; he asks, orients and discusses the way tool selection has operated. It is necessary to note that in the majority of the cases (figure 8), these means are imposed by teachers for all the design steps (35%), and (or) for certain phases (25%). In only 30% of cases these means are chosen collectively between teachers and students.

Fig. 8: Work presentation

It is then clear that the apprenticeship of the communication is centered on the nonverbal aspect. It is practiced more in the way of the representation to a given scale (drawing even without color, C.A.D to improve the quality of the drawing, model for the presentations, etc.) than in a work of simulation of the characteristics of the coming space (reality). The verbal communication and the representation by sketches seem to be the least problematical of the aspects, notably at the exploration of the problem and during the research of the solution. This proves once more that apprenticeship is less interested in the development of all the competences of communication.

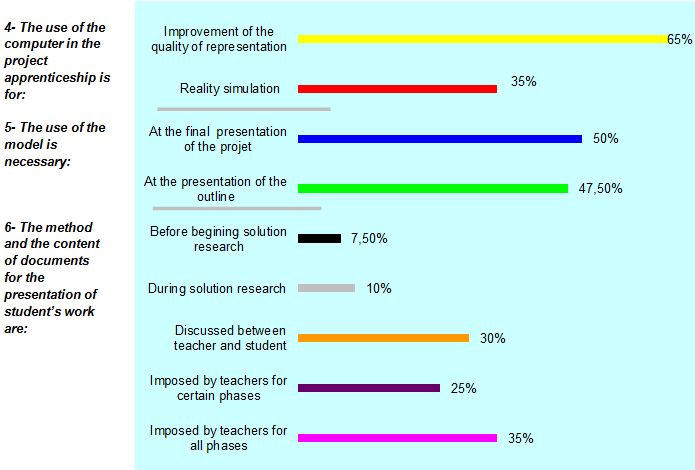

Concerning the crossing of the variables, we note that the aspect of communication constitutes the divergence point, and most notable between groups of teachers. Figure 9 shows significant differences of behavior between the main lecturers (ML) and the assistant lecturers (AL), regarding the use of color (ML, 46%, against AL, 25%) and the use of the computer for the creation of potential spaces of exchange through the web (ML, 50%, against AL, 17,9%). We note that research activities (in which the main lecturers are obligatory engaged) increase awareness about the different aspects of the project, including the question of the communication.

Fig. 9: Communication competences

Regarding the variable number of years taught in fifth year (N.Y.T.5), we note a net difference between the groups of teachers regarding the most parameters. This distinction seems to be more related to the accumulated experience and the organization of the teaching of the fifth year (final project) and the jury system. The latter constitutes a place of experimentation information and debate on all aspects of the project, including representation. Usually the constitution of the juries gathers teachers from the same department, teachers from other departments and some times exterior personalities (professionals, users, etc.) which ask students on the whole aspects of the project.

At last, we note that the verbal aspects are less taken as a problem, compared to nonverbal. This is very perceptible at the passage of the identification of the elements of the problem to the wording of the solution. The results explain that in few cases (32,5%) teachers proceed to the wording of the problem and solution by written explanations and,in the majority of cases (60%), students immediately present the solution in the form of drawings to a given scale.

The use of the drawing to a scale, as the favorite tool of communication, instead of the sketch and the model, is very noticeable during the exploration of the problem (32.5% of the cases make use of the sketch and 7.5% of the model) and in the research of the solution (32.5% of the cases make use of the sketch, against 10% of the model). This weakens the potentialities of expression skills of the architect.

Finally, we should remind that the apprenticeship of architecture prepares to a job whose practice involves the personal universe of the architect and the universe of interactions with other actors. These two universes request the architect conception and communication competences. Not attributing a lot of interests to the communication aspects means a poorly prepared architect facing the real conditions of the elaboration of the project. If, in reality, the project is a shared object between all the actors and, if during the negotiations the architect communicates by drawings and verbs (writing and speaking), apprenticeship must prepare him enough to master all the communication tools (speech, outlines, drawings, color...).

Conclusion

To conclude, we can say that we confirmed some theses advanced by different authors about the necessity of the "communication" aspects in apprenticeship and practice of the project. What is necessary, therefore, to teach to students is the need to communicate well by all means (verbal and nonverbal) and to perceive that no mean can replace the other. These means should allow anticipation and correct visualization of an absent space. The apprenticeship situations should prepare students to express themselves by the most appropriate means to every phase of learning. At last, although the present investigation relates only to the case of the project of the fifth year (final project) of the department of architecture of Constantine, Algeria, it can constitute a first idea that to foster the widening of the debate on the question of teaching the architectural project, considered as a difficult and rarely treated the subject in this country. The analysis and the interpretation of the results of the case study population allowed revealing several lacks in the educational practices of apprenticeship of the communication. It is under the light of these culminations that it is possible to confirm our hypothesis. We therefore assert that the educational practices of apprenticeship of the architectural project at the department of architecture of Constantine do not aim to develop all communicative competences of students. Concern about the aspect of teaching competences remains low and, thus, it is urgent to debate it and inject a good dose of it into the educational process. Nevertheless, the improvement of the communication competences can be achieved at two levels: in teaching the project and in teaching support courses to the project. This requires an engagement of deep thinking onto the contents, the methods and objectives of the apprenticeship. We believe that it is to this perspective that the reformation of architectural studies must be directed.

References

[1] Boudon, Philippe. Décentrer le projet. In l’Enseignement du projet d’architecture. Propos recueillis par Jean-François Mabardi, Ministère de l’aménagement du territoire, de l’équipement et des transports, direction de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme. October 1995, pp.19-29.

[2] Encyclopédie Encarta, 2005.

[3] Gillet, Pierre. Construire la formation. Editions ESF, Paris 1991. p.45.

[4] Boutinet, Jean Pierre. Psychologie des conduites à projet. Presses Universitaires de France, n. 2770, Paris, 1993, p.5.

[5] Epron, Jean Pierre. Le travail de projet, la théorie de la correction. In Les architectes et le projet, tome II, Pierre Mardaga Editeur, Liége, 1992, pp.143-246.

[6] Bendeddouch, Assia. Le processus d’élaboration d’un projet d’architecture: l’agrandissement du musée des beaux arts de Montréal. L’harmattan, Paris, 1998.

[7] Kirby Lokard, William. The recent history of design communication. In key note presentation at the design communication association, conference held in January 6/8/2000, at the University of Arizona, Tucson, spring 2000. Journal of Design Communication, Joan McLain-Kark Editor’s 2002.

[8] Chaslin, Olivier. École de Nantes, objectifs et méthodes. Document de coordination, Nantes, 2002.

[9] Kirby Lokard, William. The recent history of design communication. In key note presentation at the design communication association, conference held in January 6/8/2000, at the University of Arizona, Tucson, spring 2000. Journal of Design Communication, Joan McLain-Kark Editor’s 2002.

[10] Boudon Philippe et al. Enseigner la conception architecturale: cours d’architecturologie. Les Éditions de la Villette, Paris, 1994.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Lebahar, Jean Charles. Le dessin d’architecte: simulation graphique et réduction d’incertitude. Éditions Parenthèses, Roquevaire, France, 1983.

[13] Epron, Jean Pierre. Architecture, une anthologie. In Les architectes et le projet, tome II, sous la direction de Jean Pierre Epron, Liége Mardaga, 1992, pp.17-19.

[14] Zevi, Bruno. Apprendre à voir l’architecture. Les Editions Minuit, 1959.

[15] Conan, M. and Daniel-Lacombe, E. Concevoir un projet d’architecture. L’harmattan, 1990.

[16] Lebahar, Jean Charles. Le dessin d’architecte: simulation graphique et réduction d’incertitude. Éditions Parenthèses, Roquevaire, France, 1983, p.6.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid. p.19-20.

[19] Zevi, Bruno. Apprendre à voir l’architecture. Les Editions Minuit, 1959, p.13.

[20] Bendeddouch, Assia. Le processus d’élaboration d’un projet d’architecture: l’agrandissement du musée des beaux arts de Montréal. L’harmattan, Paris, 1998.

[21] Angers, Maurice. Initiation pratique à la méthodologie des sciences humaines. Casbah Université, Alger, 1997.

[22] Conan, M. and Daniel-Lacombe, E. Concevoir un projet d’architecture. L’Harmattan, 1990.

[23] Bendeddouch, Assia. Le processus d’élaboration d’un projet d’architecture: l’agrandissement du musée des beaux arts de Montréal. L’harmattan, Paris, 1998.

Cite this paper

APA

Aiche, M., & Derradji, M. (2012). Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences. Open Science Repository Architecture, Online(open-access), e70081915. doi:10.7392/Architecture.70081915

MLA

Aiche, Messaoud, and Mohammed Derradji. “Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences.” Open Science Repository Architecture Online.open-access (2012): e70081915.

Chicago

Aiche, Messaoud, and Mohammed Derradji. “Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences.” Open Science Repository Architecture Online, no. open-access (December 28, 2012): e70081915. http://www.open-science-repository.com/teaching-the-architecture-project-educational-practices-and-communication-competences.html.

Harvard

Aiche, M. & Derradji, M., 2012. Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences. Open Science Repository Architecture, Online(open-access), p.e70081915. Available at: http://www.open-science-repository.com/teaching-the-architecture-project-educational-practices-and-communication-competences.html.

Nature

1. Aiche, M. & Derradji, M. Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences. Open Science Repository Architecture Online, e70081915 (2012).

Science

1. M. Aiche, M. Derradji, Teaching the Architecture Project: Educational Practices and Communication Competences, Open Science Repository Architecture Online, e70081915 (2012).

doi

Research registered in the DOI resolution system as: 10.7392/Architecture.70081915.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.