Open Science Repository Sociology

doi: 10.7392/Sociology.70081921

Evidence of promoting the use of condom as a public health intervention to prevent HIV transmission in East African Community region

Kigali Institute of Science and Technology (KIST)

Abstract

EAC is an intergovernmental organization comprising the five east African countries: Rwanda, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Burundi. East African Community is now hosting a total population approaching 13 Millions. EAC launched the common market regarding capital, goods, labor and services within the region in July 2010. This could cause different interactions including social activities such as unprotected sex that often result in the transmission of HIV within the community members. Due to the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS status in East African Community (EAC), the promotion of condom use through different campaigns would be a key to combat against the transmission of that particular infectious disease within the EAC. According to the US center for disease control and prevention, without use of condoms, other HIV preventive measures lose their effectiveness. In addition to sexually transmitted diseases prevention, condom can serve also as both a family planning and unwanted pregnancies prevention tool. In Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda, there is a low level of modern contraceptive use among young women; for example, about 35-40% of young women reported ever being sexually active in Uganda and Tanzania. Therefore, condom use promotion as a contraceptive method could enhance as well its consistence use prevent HIV/AIDS transmission in all EAC countries.

Keywords: condom use, HIV transmission, East African Community, public health.

Citation: Rutanga, J. P. (2013). Evidence of promoting the use of condom as a public health intervention to prevent HIV transmission in East African Community region. Open Science Repository Sociology, Online(open-access), e70081921. doi:10.7392/Sociology.70081921

Received: December 31, 2012

Published: April 29, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Rutanga, J. P. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Contact: [email protected]

Full text

Use of condoms or non-use of condoms has been of particular interest to public health researchers trying to describe the young people’s sexual behaviour. Condoms are of clinical interest because of their dual role in protecting against pregnancy while simultaneously reducing risk of transmission of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV (Marston, 2004). Abstinence, faithfulness and use of condom have been suggested as the main strategies to prevent the HIV/AIDS transmission; but successful prevention programmes need to contain a balanced response, it is in nobody’s interest to undermine the extremely valuable role that condoms have to play in HIV/AIDS prevention. It is naïve in the extreme to believe that entire populations of sexually active adults can abstain or be faithful. Condom use has to be promoted as the main method of prevention, to enable people to make a well informed choice and therefore protect their sexual health.

The Human Rights Watch (2004) emphasized that to promote the condom use as a way of limiting the HIV /AIDS through the campaign must be done in conjunction with local governmental leaders, non-governmental organizations, and private sectors. An educational program is necessary to make educated and non-educated people aware of the effectiveness of condoms, in spite of their usual social, religion and cultural predictions regarding condom. There are many evidences of effectiveness of condom use promotion’s intervention; Cambodia is one of the countries where condom use was promoted successfully (WHO, 2001).

Thailand, Cambodia and Uganda are the most evidencing countries where promoting condom use has been successful. In Thailand, Uganda and Cambodia, programs promoting condom use have reduced HIV transmission in both sex workers and their clients, without forgetting the whole population in general (David, 2006).

Due to the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS status in East African Community (EAC), the promotion of condom use through different campaigns would be a key to combat against the transmission of that particular infectious disease within the EAC. According to the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, without use of condoms, other HIV preventive measures lose their effectiveness (UNAIDS, 2004). In addition to sexually transmitted diseases prevention, condom can serve also as both a family planning and unwanted pregnancies prevention tool. In Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda, there is a low level of modern contraceptive use among young women; for example, about 35-40% of young women reported ever being sexually active in Uganda and Tanzania (Shane and Vinod, 2008).Therefore, condom use promotion as a contraceptive method could enhance as well its consistence use prevent HIV/AIDS transmission in all EAC countries.

EAC is an intergovernmental organization comprising the five east African countries: Rwanda, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Burundi. East African Community is now hosting a total population approaching 13 Millions (Aylward, 2004). EAC launched the common market regarding capital, goods, labor and services within the region in July 2010. This could cause different interactions including social activities such as unprotected sex that often result in the transmission of HIV within the community members.

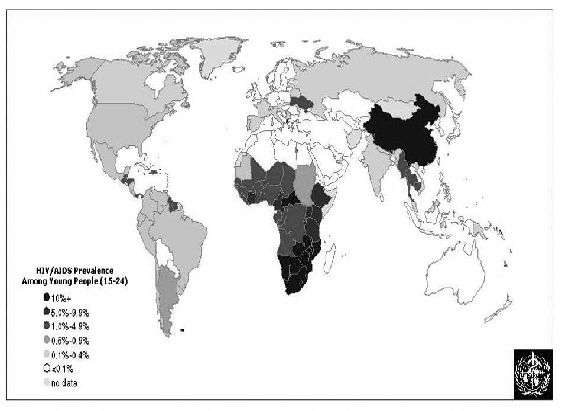

Figure 1: About 11.8 million young people (15-24) are living with HIV/AIDS (source: WHO, 2004a).

Darker shading on the above figure shows areas with greater levels of HIV infection. The highest level of HIV prevalence marked in East African countries, according to the figure, emphasizes the reason why the promotion of condom use is needed in that particular region.

Despite the effectiveness of condoms to reduce HIV/AIDS transmission, condom use consistency in EAC remains limited to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS infection. The use of condoms must be a big concern for public health practitioners within this region. Condoms, in case they are used correctly and consistently, are the only way of protection that can help people to stop the transmission of sexual infections (STIs) such as HIV (Alta, 2008). This is one of the evidences why the use of condom should be promoted in big communities with various sexual behaviours such as the East African Community. EAC leaders should think about the link between HIV and mobility of people, by establishing a common coordinating mechanism on condom use promotion to prevent HIV transmission.

Uganda is counted among the world’s successful countries to fight against HIV, due to the epidemic prevalence decline it has experienced during 15 years ago (USAID, 2002).

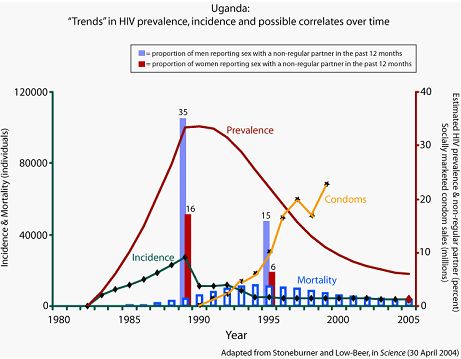

Figure 2: Trends in HIV prevalence, incidence and possible correlates over time (source: EAC, 2009).

In Uganda’s generalized epidemic, efforts to encourage people to limit their sexual partners played a central role in Uganda’s early approach to HIV prevention, and appear to have contributed to significant HIV prevalence rates in the last 1980s and early 1990s. Interestingly, there seemed to be little change in teenage pregnancy rates from 1989-1995, the period in which incidence seemed to decline most dramatically. A recent paper presented at the 2005 retrovirus conference concluded that deaths contributed a lot to declines in HIV prevalence in Rakai, in the study period of 1994-2002 following the period in which Uganda experienced its dramatic declines in HIV incidence (Gray et al., 2006).

According to this new paper, the rates of new infections remained fairly stable in Rakai after the dramatic declines of the late ’80s and early ’90s. This later period was characterized by increases in reported condom use, but also by increases in the number of individuals reporting more than one sexual partner. There also may have been slight decreases in the median age of sexual initiation among males. Some argue that the programmatic emphasis migrated away from “B” and towards “C” during this later period, and that consistent emphasis on all three of the “ABCs” of prevention might have resulted in continued declines in HIV incidence.

According to the above graph, the most recent demographic and health surveys (DHS), which included a linked HIV biomarker, found that adult prevalence in Uganda is now 7% (the UNAIDS estimate is 4.1%), and that 39% of sexually active men and 18% of sexually active women reported sex with a non-marital, non-cohabitating partner in the past year. 41% of women and 50% of men reported condom use at last sex with a non-marital, non-cohabitating partner.

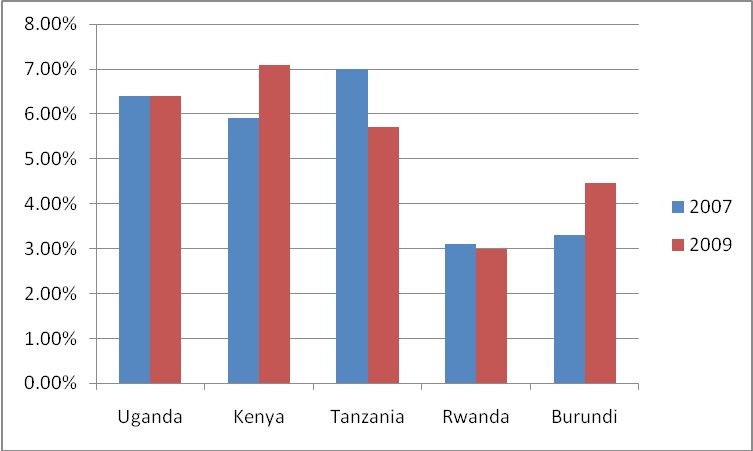

Uganda was the first of the East African Community countries region to declare HIV cases in 1982. This was followed by Kenya in 1984 (Kolipeni, 2004). n 2007, HIV prevalence among adults in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda exceeded 5% (ref. 23) .In Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, by the end of 2005, about 3.7 million were living with HIV/AIDS within a total of 107 Million people; 3.4 million positive HIV/AIDS were 15-49 years old (UNAIDS, 2006a).The HIV/AIDS prevalence between 2003 and 2006 in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi was 6.4%, 5.9%, 7%, 3.1%, 3.3%, respectively (EAC, 2007). Recent HIV/AIDS prevalence data in EAC countries show that the prevalence does not generally decrease sensibly up to 2009. The prevalence stands at 6.4%, 7.1%, 5.7%, 3%, 4.46% in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi respectively (EAC, 2009b).

Figure 3: HIV/AIDS prevalence data from East African Community Regional HIV status report (source: EAC, 2009b).

By plotting the HIV/AIDS prevalence data for both 2007 and 2009 on the above figure 1, it can well be seen that only Tanzania and Rwanda made an improvement, decreasing their HIV/AIDS prevalence from 7% to 5.7% and 3.1% to 3%, respectively, whereas prevalence has increased from 5.9% to 7.1% and 3.3% to 4.46% in Kenya and Burundi. HIV/AIDS prevalence remained constant in Uganda within those two years. This means that the whole five countries have to work hand in hand to reduce the HIV/AIDS prevalence by promoting the use of condoms within the East African Community.

Uganda should be a typical model for the rest of EAC countries to prevent HIV transmission. After getting enough information about Uganda’ successful historical background, let us see how are HIV epidemic status and condom use conceptions among the other four EAC countries.

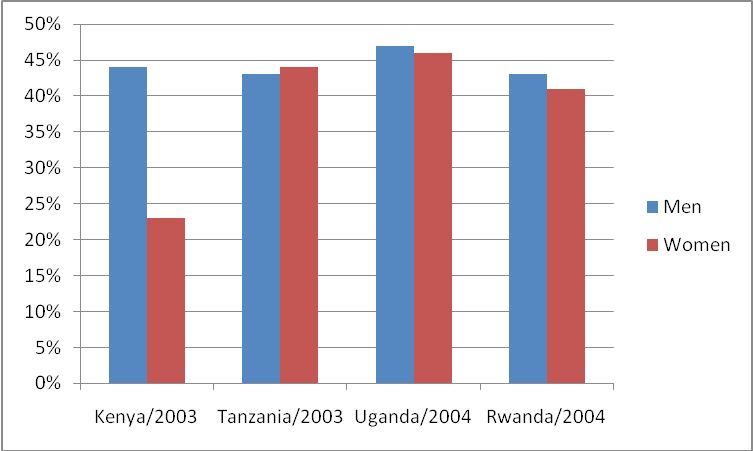

Due to the mobile population from one country to another, having different sexual behaviors, there should be serious intervention of use of condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS transmission among the population within this community. Despite the effectiveness of condoms to reduce HIV/AIDS transmission, condom use consistency in EAC remains limited to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS infection. Therefore, in EAC, we need excellent interventions to promote the condom use as a principal mean to prevent HIV/AIDS transmission. The same idea of preventing HIV/AIDS using condom promotion was argued in a research carried out in Brazil (Mariangela and Ina, 2005). A survey conducted between 2001 and 2005 indicated that young men were more to use condom during intercourse with non-regular partner, compared to young women.

Figure 4: Comparative use of condoms in percentages between young men and young women in four East African Community countries (source: UNAIDS, 2006a).

Condoms are not more popular everywhere in EAC countries. It can be well explained that the main reason to failure of using condoms may be highly associated with their social and cultural considerations about sexuality. The main reason why individuals report not using condoms is that they do trust their partners (Agha, 2002). As well as partners become committed to each other, they end up by stopping condom use (Longfield, Glick, Waithaka, Berman, 2002). Some people don’t consider as appropriate for a family to use condoms with a spouse. Van Rossem, 2001, in his research, supports the issue that spouses are less likely to use condoms than partners.

Talking openly about something related to sex within the family in Rwanda, as well as in the whole EAC, is seen as shameful. For example, in Rwanda, rural Rwandans have their own way of conceptualizing the sexual intercourse relationship. Most of them consider it as an important way of exchanging the “gifts of self” (Alta, 2008, pp.209). Thus, considering the use of condoms as a way that could block that exchange, fertility and also causing some sorts of illness, many Rwandan women fear that the condom could remain in their vagina after intercourse. Not only the problem of social and cultural mentality harms the promotion of using condom, but also its availability.

Less than 50% of the required public sector condoms are the ones which are supplied globally by UNFPA (UNAIDS, 2006b). HIV/AIDS programmes in the East African Community must take into account not only the availability of condoms, but also its quality. This can be demonstrated by the distribution of defected condoms which happened in Uganda around 2005, where they have ordered condoms with holes and bad odor (Philip, 2008). The main consequences to such incidences are the loose of confidence affecting the use of condom, because people will always think that the actual condoms could be with the same quality as the ones distributed at that time. From that, it can be realized that condom use must be advertised and publicly promoted as a successful mean to prevent HIV transmission among EAC population. This is what USAID suggested to be done at country level in Sub-Saharan countries including EAC; by encouraging private sectors to produce qualitative condoms and make them available to the population in need (GAO, 2001). UNAIDS states that the mismanagement in making condoms more available to people, by its distribution in Uganda, has led to 35%, 59%, 53% and 57% of men against 20%, 39%, 47% and 35% of women in 1995, 2000, 2004–2005 and 2006 respectively, using the condom with their non-partner (ref. 22). On the other hand, the condom availability in EAC countries does not totally mean its use!

It has been viewed that despite the number of condoms distributed in 1993, in Uganda, only 3% Ugandan men were found adequately and regularly using condoms (Alta, 2008). The condom use and its non-use may depend on the population’s thought about it; where by the experience in my home country, Rwanda, condoms are most of the time used as children entertaining items. Apart from the problem of condom availability and its use among the EAC dwellers, there are also some other cultural or social barriers common to all EAC dwellers that harm the condom promotion.

Cost has been found to be also harming condom use. Free or affordable condoms in terms of price should be distributed to promote their use by persons at risk for HIV and other type of sexually transmitted diseases (Cohen, Scribner, Bedino and Farley, 1999).

The use of condom promotion could encounter traditional sacred conceptions within the EAC. The most important one is the idea of considering the use of condom campaign as a way of tackling the African population and cut off or minimize the man’s usual dignity among the whole population.

The low level of condom use in Rwanda is mostly a result of lacking awareness and unavailability of condoms, especially in remote villages. According to the Rwandan National HIV/AIDS control commission, about 14 millions of condoms are the only that are imported to be distributed into villages. And people in villages are always claiming that condoms are not enough (ref. 5). It is estimated that, in Rwanda, the most sexually active people use about 3 condoms per year in average; this number is surprisingly low (Global HIV/AIDS news and analysis, 2010). The most challenges faced in promoting the efficiency use of condom in Rwanda are associated with the people’s sexual behaviour and the unavailability of condoms in most rural villages. One of the greatest challenges is how to overcome cultural considerations of the use of condom, common in Rwandan villages. Poor communication models, religions and lack of the government commitment are most of the time harming condom use’s campaigns. To overcome all those obstacles, serious and strong campaigns are needed.

The Rwandan National HIV/AIDS control commission should increase the number of imported condoms. Awareness of condom use must be emphasized among youth, especially those living in towns; because it has been stated that condoms are more likely used by people living in villages than in towns (ref. 5).

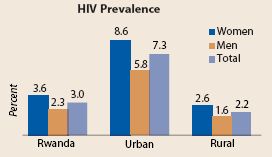

Figure 5: Rwanda has a generalized HIV epidemic (source: EAC, 2009a).

The above graph represents the HIV epidemic in Rwanda which is mostly encountered in the urban areas compared to rural areas.

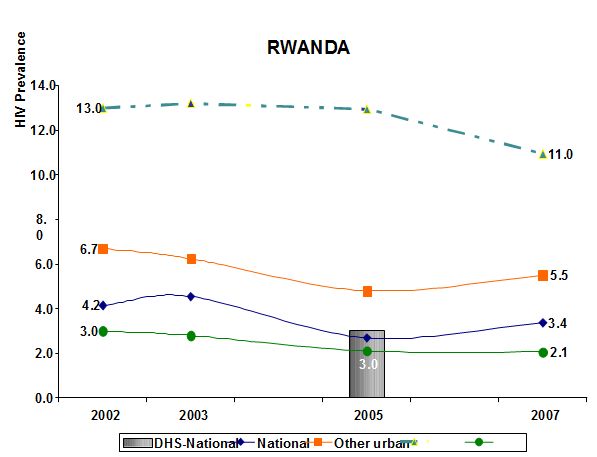

Figure 6: HIV prevalence 2002-2007 in Rwanda (source: EAC, 2009a).

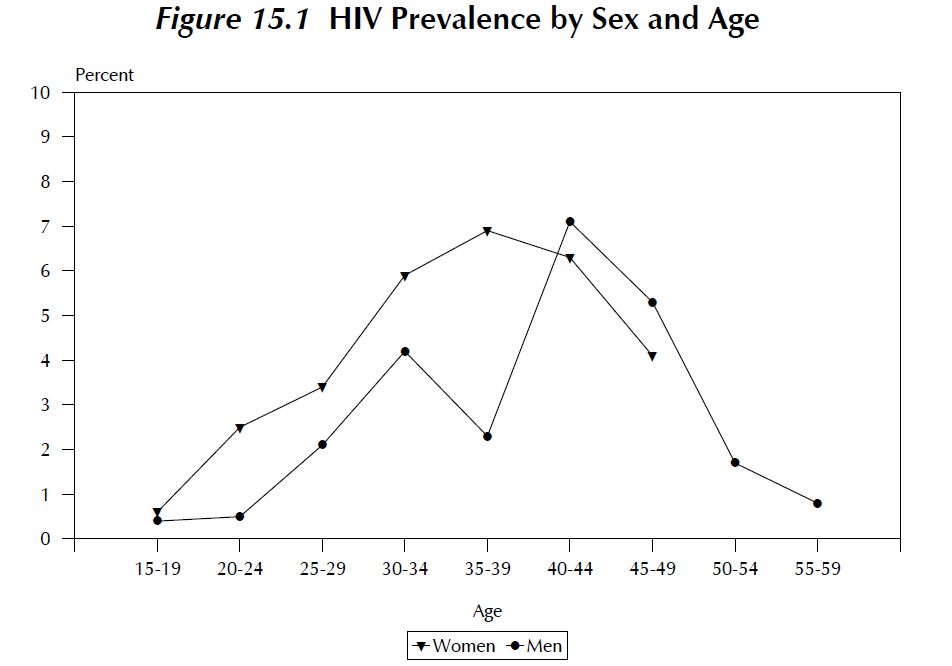

Figure 7: Disparity in age and sex HIV prevalence in Rwanda (source: EAC, 2009a).

Age/sex distribution of HIV prevalence probably suggests that younger women may be infected by older men. Younger women are infected earlier by older men, but HIV prevalence increases with age in case of men and women. However, the 35-39 ages group is the one showing the highest prevalence in women (6.9 percent); figures are different in case of men, among them is the 40-44 age group which manifest the highest prevalence (7.1 percent). The number of infected men is lowest than the number of infected women from 15-19 age group up to 35-39 age group. Afterwards, the situation shows different patterns because 4.1% of women at age of 45-49 are infected (positive) compared to 5.3% of men.

Campaigns should be done by extending programs teaching how to use a condom and its importance. This can be facilitated by using internal or local radios and billboards on all roads, in order to spread the information about the usefulness of condom use to prevent the HIV/AIDS transmission. Since about a half of Rwandan condom users is still complaining against the insufficient information on the efficient use of condom (Global HIV/AIDS News and Analysis, 2010), the promotion of “condom use” must be considered as a national strategy to prevent the HIV/AIDS transmission among the Rwandan population. The purpose of condom use campaign would be to make sure that condoms are available where they are in need, and if they are really used correctly.

Condom use campaigns must focus more on Rwandan youth, because if any one use condom for his or her first sexual relationship, he or she is more likely to continue using it even for the other subsequent sexual acts (Igham and Aggreton, 2006). Organising different sport disciplines would be also one of the best ways to meet young people and tell them about the benefits of condom use, as one of the efficient HIV/AIDS preventive methods.

For the best way of distributing condoms, health workers in each rural village would play a big role to spread condoms among the population. Both in towns and countryside, condom vending machines should be installed into bars, night-clubs, stadium and other different entertaining places. Public and private sectors should take the condom distribution into their accounts. Rwanda revenue authority could allow the importation of condoms by fixing low taxes condoms importers. Afterwards, the selling price will be low and affordable even for those people with low-income. This will generate a good contribution to the use of condoms in Rwanda, because the less expensive condom could be, the higher condom sale rates would be. Definitely, if condoms are available for everybody, the HIV/AIDS transmission will be decreased among Rwandans by this way.

To overcome Rwandan cultural sex behaviours which do not allow most of the parents to talk to their children about condom use, many encouragements are needed. Parents should start to speak to their children about the use of condoms; of course, parents are the ones to be convinced first by the idea that the use of condom is necessary in case anyone fail to abstain.

The use of condom is not simply a practical act, but also it has other social meanings. Doing sexual intercourses without using a condom is often considered as trustiness sign. If you are in relationship with someone and then later you start using condoms, it is then a sign of the relationship cessation; the same with someone who asks his/her partner to use a condom, it is a symbol of trustless among the couples. Other reasons of not using the condom in the society is that of fearing to lose an erection during sexual intercourse; and this could be one of the symbols of not being a powerful man.

If you choose to wear condom before your sexual act, you appear to have AIDS, because there would be no need to use a condom in case you normally behave well. They still consider it as a specific for prostitutes only.

The condom use frequency in Tanzania was more found in urban areas than rural villages (Kapiga, 1996). Women in one of Tanzanian rural areas, Mwanza, prefer not insisting on condom use in case their partners refuse (Plummer et al. 2006).Tanzanian students who do not use condoms consistently are mostly the ones whom their parents do not like condoms (Maswanya et al.1999).

During one particular study on condom use in Tanzania, men and women who declared one partner in their past four weeks were almost three times more likely to report condom use during their sexual intercourses (Kapiga, 1996). Nevertheless, education was found to be a factor to the use of condoms. Men with greater education level were more likely to use condoms in their last four weeks than those with lower education (Kapiga, 1996).

A study of results with 15 to 44 years old in rural Tanzania came out with results that, even if the HIV/AIDS prevalence was higher from 5.9 to 8.1% from 1994 to 2000, most people did not care about the risk for HIV/AIDS, for there was only a limited use of condom (Mwaluko,2003).

In Tanzania, the number of individuals who know where to obtain condoms are still low, with approximately 52.2% and 72.2% of young women and men respectively reporting that they may know where to get condoms (Tanzania commission for AIDS, 2005). One of the reasons to the obstacle of obtaining condoms when they are needed is that most of the youth are not assured for the providers to keep their confidentiality (Plummer, 2006). In many regions, people are ashamed to declare that they need to buy condoms. That is why many girls cannot go to the nearest pharmacies or shops to buy a condom package; because they feel shame themselves to be considered as prostitutes by going around to buy condoms. The same with men, they do not want be considered as having a lot of women.

During a Tanzanian national survey on the use of condom, knowledge about condom use as a way of preventing HIV/AIDS transmission was found still limited. About only 43% of men and 58% of women did not mention condom use as an HIV/AIDS preventive measure (Kapiga, 2003). According to the same Tanzanian national survey, condom use was found to be higher among large cities’ residents as well as among people with a higher educational level; and level of condom use among women was low compared to men.

In Kenya, the risky sexual behaviour was found to be associated with ethnicity. Lack of education was again pronounced as an essential barrier to condom use (USAID, 2008), as an increase in the differential condom use was marked between urban and rural villages. This show how there is a need to reduce condom use unbalances by applying different appropriate campaigns.

High risky sexual behaviour was reported by young women and men due to their usual multiple partners and their unprotected sexual intercourses (Akwala, Madise and Hinde , 2003).

The Kenyan diversity in culture, with about 41 different tribe cultures, causes a variation in conceptualizing the sexual behaviour. The low condom use in Kenya is mostly due to the low perception of risk for HIV/AIDS, the obstacle of stigma for buying condoms and the insufficient knowledge about the effectiveness of condoms to protect HIV/AIDS (Longfield, Glick, Waithaka, Berman, 2002).

William (1999) reports results of a study conducted on different perceptions of condom use in three sites of Kenya: Simba, Mashinari and Malaba. Most of participants in this study responded that based on their own experience, they do not think that condom could be an effective measure to prevent HIV/AIDS. The first reason for that was the condom breakage which marks its inefficacy. The low rates of condom usage were found associated with the unavailability of condoms in those three sites. The problem of insufficient condoms was raised in Malaba region, a town on the Uganda border, where many drivers look out for local commercial sex workers while they remain there for multiple nights to wait for their cargo to clear customs. In addition to condom availability, there is also the problem of quality in condom storage. Some boxes of condom were found in places where they may be rained upon, and other ones left in places where they could be damaged by the sun rays. Some participants suggested that they may prefer real sexual intercourse, which means without using condom, as their preferred enjoyable way of having sex. The use of condom was seen as a true barrier to real sex even among commercial sex workers. For them, they choose men ejaculating into them directly in order for the sex act to be pleasurable and successful. Therefore, some participants declared that some of their partners use to break intentionally the condom during sexual intercourse for the condom not to act as the barrier.

According to the USAID report, condom use in Kenya remains below 50% (USAID, 2008). In this report, it is stated that there is a significant difference in condom use between urban and rural areas, due to the fact that most participants who reported to engage in higher-risk sex live in rural areas. That is why condom use promoting campaigns are needed more in rural areas than in urban areas. Lack of education as a barrier to frequent condom use in Kenya was also reported in that report. The lower level of condom use was again reported in central regions than in eastern regions of Kenya within the same report. While condom use programmes were usually designed for youth in EAC countries, the same report confirmed that older men had lower levels of condom use compared to young men. Given the high widespread and prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Kenya, there is always a low use of condom.

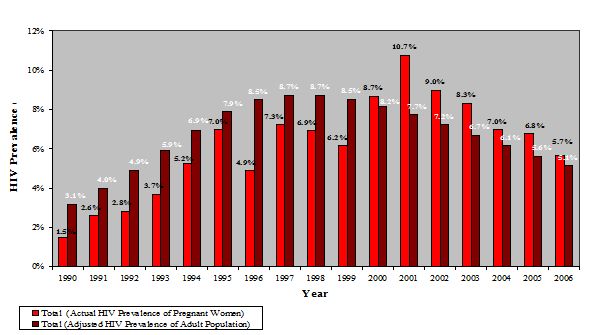

Figure 8: HIV trends in Kenya (source: EAC, 2009d).

According to the above graph, since 1990 the highest HIV prevalence among pregnant women was observed during 2001, when it has reached up to 10.7%. On the other hand, considering the whole adult population, 8.7% as the highest HIV prevalence rate was observed in 1998. The recent data of 2006 shows that the HIV prevalence on both sides, pregnant women and the adult population, has decreased up to 5.7% and 5.1% respectively.

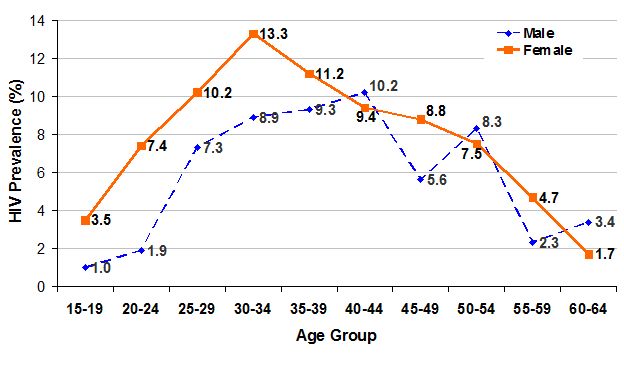

Figure 9: HIV prevalence by age and gender in Kenya (source: EAC, 2009d).

The 15-34 gender’s gap is greatest. There is still substantial infection among older adults. Men having more than 55 years have higher infections than 15-24 age group. This shows how much the condom use intervention in Kenya could focus more on young women and older men. New infections probably run the range of ages (not exclusive to youth population).

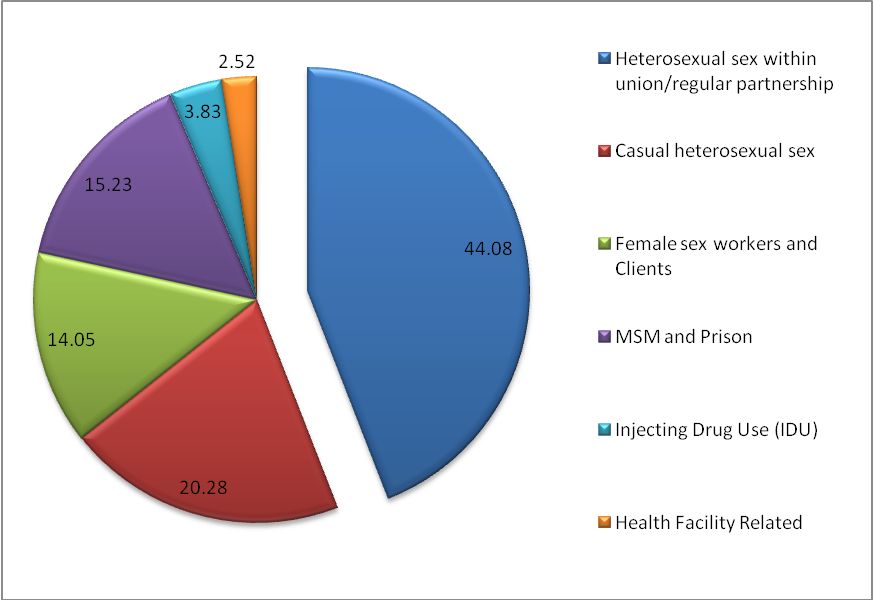

Figure 10: Where and how did HIV new infections occur in Kenya? (source: EAC, 2009d).

Men who have sex with men (MSM) and injection drug use (IDU) combined contribute up to 19% of new infections. There is evidence of increased risk of HIV transmission (44.08%) in regular partners of sex workers and regular partners of sex worker clients, which may be caused by the lack of condom use.

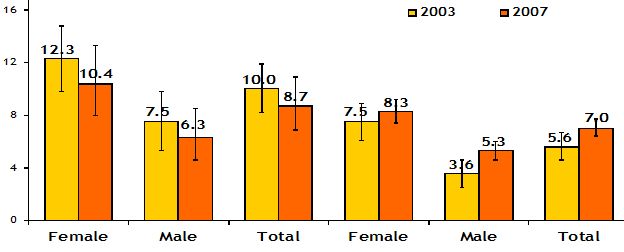

Figure 11: HIV prevalence by residence and gender in Kenya (source: EAC, 2009d).

The above figure represents the non-significant trend towards lower prevalence in urban areas and trend towards increasing prevalence in rural areas. The significant increase of HIV prevalence is marked among rural men more than women.

Figure 12: Consistent condom use in married couples by PLWH in Kenya, 2007 (source: EAC, 2009d).

This graph shows a consistent condom use in marital and cohabiting sexual partnerships by knowledge of HIV status. Respondents who knew their HIV status were more likely to use condoms consistently compared to those who did not know their HIV status. Therefore knowing the HIV status was the main reason of using condom among partners.

Almost one over five men declared to have ever used a condom during their last sexual intercourse, whereas one in ten women declared to have ever used a condom (Waithaka and Bessinger, 2001). Educational attainment level in women was found to be associated with their condom use; education provides women with a certain confidence to negotiate condom use before sexual intercourse with their partners. This shows really how the education confers a level of awareness of the risks in having unprotected sex. The same with women living in urban regions, who were more found to use condoms than women living in rural villages; this may be due to better acceptability and availability of condoms in urban villages compared to the rural villages. Even if a large number of condoms were distributed nationally in Kenya in 1998, a high number of people do not know where they could obtain a condom. This is a big problem, as the knowledge of a place where to get a condom could be associated with the frequent use of condom. Therefore, effective campaigns are needed to promote the use of condom in Kenya.

Education was found to be necessary to promote condom use in Burundi, because in that country there are still most people who think that condom may contain HIV itself and they are the uneducated ones (Hausser, 1993). So they cannot believe the effectiveness of condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS transmission. Also, insufficient number of distributed condoms in Burundi was marked in that Hausser’s article.

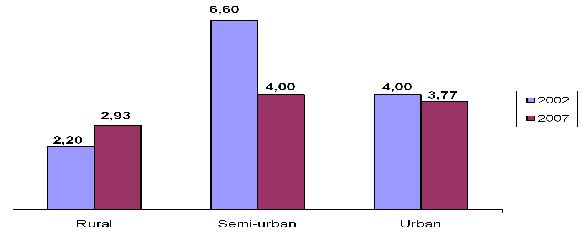

Figure 13: Prevalence rate in 2002 and 2007 among young women and men aged 15-24 years in Burundi (source: EAC, 2009c).

Higher HIV prevalence among Burundians aged from 15 to 24 years old was more encountered in semi-urban compared to rural and urban areas; during 2002, semi-urban prevalence was 6% compared to the recent rate of 4% in 2007.

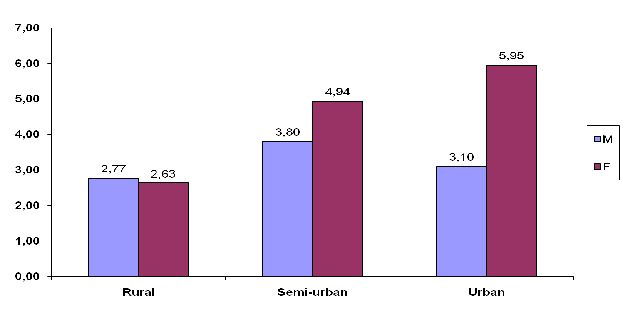

Figure 14: HIV prevalence rate by sex in 2007 among general population, 18 months and more in Burundi (source: EAC, 2009c).

The HIV infection was found to be more prevalent among females compared to males in 2007 in urban and semi-urban areas, which is different from rural areas, where the highest prevalence was found among males.

Figure 15: HIV prevalence rate by age in 2007 among general population, 18 months and more in Burundi (source: EAC, 2009c).

The 25-49 ages group was found to be more exposed to HIV infection in all urban, semi-urban and rural areas. This shows how the condom use campaigns should target this particular age group, in Burundi.

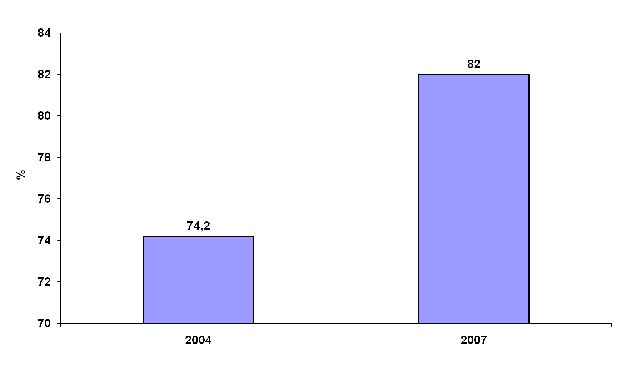

Figure 16: Percentage of sex workers reporting the use of a condom with their most recent client (source: EAC, 2009c).

The condom use rate has increased from 74.2% in 2004 to 82% in 2007 among sex workers. As there is evidence of increased risk of HIV transmission (44.08%) in regular partners of sex workers (figure 10), this should be another targeted group for condom use intervention to make the condom use rate among sex workers increased up to 100%.

It can be observed that the five countries share almost the same epidemic prevalence, condom misconceptions and barriers; therefore, the same condom use intervention can be applied everywhere in the whole community.

Obstacles to use condoms include less awareness of condom use, unavailability of condoms, people’s self-perceptions and beliefs of condoms, and their relationships with partners. Cultural environment may not be favourable to support the provision of knowledge and skills regarding condoms. Gender inequalities could be an obstacle, because some people may think that condoms are made for boys and not for girls. Condoms are not affordable for people with no income, like adolescents. Many people claim that using condoms might be equal to being promiscuous. According to some people, they think that using condoms procure loss of pleasure, and that is the main reason for them for not using a condom (WHO, 2004b). Within the same mentioned WHO report, there are people who believe that condoms might be manufactured with holes so that people using them could become infected easier. So, this intervention is designed to brush aside and explore all kind of misinformation about condom use with adolescents. A number of people is still considering condom as appropriate to western culture, thinking that it could be ineffective, unpopular or unreliable for African culture (WHO, 2004b).

Therefore, major specific objectives of the condom use intervention in EAC are:

- Changing people’ behaviours to successfully negotiate condoms use before sexual intercourse;

- To reduce HIV/AIDS transmission among EAC dwellers as much as possible;

- To increase the level of condom use over 95% both in EAC towns and rural areas;

- To strictly control HIV/AIDS among EAC population;

- Provide access to condoms for all EAC people;

- To define and suggest possible campaigns for condom use in EAC;

- To suggest possible common EAC partnership that will be required to support and accelerate the condom use intervention in EAC.

Condoms, in order to be effective in the whole EAC, must be promoted among the high risk population. The high risk population includes sexually active young people, sex workers and their daily clients and people living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2004). Condom use campaigns should target young women and men and individuals with less educational background, to increase condom use knowledge as a specific HIV/AIDS preventive measure in EAC. Condom use campaigns for HIV prevention should ensure sexually active young people to have easier access to good quality condoms and know how to use them consistently and correctly. Condoms should be taught to be used for all first-time sex and for any other subsequent sex act except for a couple looking for a baby.

For young people, condom use intervention need to be addressed for the following categories:

- All adolescents before they are sexually active;

- Adolescents who are sexually active;

- Young people who didn’t attend school;

- Young people engaged into prostitution.

Generally, adolescents need to access information about HIV transmission and its prevention; they need information much linked to their daily life, like how to prevent such sexually transmitted diseases (WHO, 2004a). They are eager to know how HIV/AIDS spreads and how it is prevented. Young people accept information when and where they gain it, which could be from friends, family relatives, teachers, posters or any kind of mass media (WHO, 2004b). They must talk to their partners about the use of condom before they start their sexual act and be able to use them correctly. Increased condom use among adolescents is most effectively achieved when accompanied by behavioural change campaigns, which is necessary to support the consistence and correct use of condoms (WHO, 2004a).

Parents, local community health leaders and other important people within the EAC society should be encouraged to support the condom use promotion, because those are the main ones who could help informing the whole community about the benefits of this intervention. This will need again support from traditional and cultural leaders, community leaders, traditional healers and the concerned population as well (WHO, 2004b).This is the only way of overcoming the people’ existing opposition and beliefs to the use of condom.

The promotion of condom use should also be done through traditional healers. Traditional healers could be effective to promote the use of condoms, for they are considered psychologists, marriage and family counselors, physicians, priests, legal and political advisers. They are the guardian of traditional morality and values. They are the one to interpret rules of contact and they have capacity and authority to change and invent rules by influencing people in matters relating to sex. They are usually considered credible as they work in treating STIs in most of EAC countries (Edward, 2003). So the aim would be to convince traditional healers to counsel their clients on the use of condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS transmission.

In spite of local taboos that surround talking openly to people about sex, an educational program about the use of condom must take place. For example, sex is rarely discussed within the population in Rwanda (Laura et.al, 1999). Peer educators could play a big role in changing people’s behaviours (UNAIDS, 2003). They will be trained to facilitate discussions about HIV risk-behaviour. Peer educators are the ones who could maintain a link between the condom use intervention and the EAC people. Providing training skills on how to use condom correctly and how to discuss about its use with individuals’ partners are more effective than providing only the condom use information.

Following will be the main contributions of trained peer educators for this particular intervention:

- Conduct discussions with people (peers) about safe sex practices;

- Training people in condom negotiation and condom use with their sexual partners;

- Motivating people to use condoms;

- Helping in condom’s social marketing.

By the way, one could ask himself why to use peer educators to promote the use of condoms in the EAC? The response would be that, according to other interventions, various where peer educators were used, it was found that: they were less costly, they were the ones to break (change) people’s behaviours and maintaining confidentiality and they were most effective by sending the correct and true message to the target population (UNAIDS, 2003). To achieve the condom promotion’s goals, peer educators have to be accessible and available to the target population at all required times, motivated by the condom use concern, be respected within the community and be able to speak the languages of the EAC targeted groups.

So, condom use intervention should work in support by those partners to provide enough information for young people regarding HIV prevention and will aim to the practice of negotiation skills for condom use among partners. As evidences show that young EAC people are engaged in sexual activity, condom use intervention could make them aware of HIV infection and its preventive measure using a condom (Mitchell et al., 2001). Young people need to develop skills to delay having their first sex and argue the use of condoms.

Young need to be informed about where exactly to get condoms at even a low price they can afford. Because young and poorer seem less to pay themselves for condom, even if they may be willing, they lack the ability to pay for it (WHO, 2004a).

Community health workers should be able and eager to offer condoms; a better and reliable condom distribution should consider and ensure the availability of condoms in these following places:

- Public clinics and hospitals;

- Pharmacies and kiosks;

- Community level distribution;

- Cinema and discos;

- Schools;

- Working places;

- Condom vending machines.

It is better to consult people about where they think it should be good for them to easily get condoms. It is good always for public and private sectors to get involved in social marketing to promote the condom use (WHO, 2004b). In order to make condom available, different condom’s distribution mechanisms can be taken into account. These may include:

- Health and social service organizations as they are closer to many people and can play an important role for the marketing and distributing condoms in rural areas;

- Public health practitioners must provide guidance on how to keep all condoms in their proper store and communicating at the same time people where to get those stored condoms. This will facilitate people’s awareness of their nearby condom’s store;

- For those who have internet facilities, an online condom ordering system can create an excellent condom distribution mean; especially in cities and towns.

There should be a way of selling condoms at low price; the main selling locations should meet sex workers and their clients. Condoms marketing should be accompanied by advertising campaigns such as mass media, without forgetting the distribution of free condom samples.

The above suggested distribution means have been recommended to be effective in New York City (Renaud et al., 2009).

In spite of the discussed significant predictors of condom use among EAC countries, different campaigns are needed to improve the condom use to reduce HIV/AIDS transmission. There are many condom use campaigns methods which could be used to promote the use of condom in EAC. However, there is no particular campaign guaranteed to successfully encourage EAC members to use condom. Therefore, condom’s promoting campaign may be effective due to the local population beliefs. To determine which campaign to use within a particular EAC country, it is necessary that representatives from that country are invited to make a comment on one of the campaign’s methods and the appropriate locations to be applied for a successful condom promotion. Use of posters, leaflets and flyers, magazines and newspapers, radio and television, calling cards, freebies, tickets, organising visits, open days and special events, all of them essential campaigns to promote the use of condom in EAC. Posters are the most popular and they should be frequently used in within the EAC community.

The poster’s design should not contain much text and information. Posters containing too much text and information are annoying, especially for people who do not have enough time to stand in front of them and read the whole information in words. Information is better to be put into pictures; in this case, condom pictures must be used to transmit the protective sexual relationship message. Apart from condom pictures, posters should include enough contact details for anyone who would like to seek for enough information regarding condom and its use. The most important aspect of the posters is to make sure that both the text is readable from an appropriate distance. Because due to the local population’s sexual behaviours, some people in EAC may prefer to be able to read the poster information without any other people know that she or he is doing so (St. Lawrence, 1996). This is always important, especially for the contact details which should be written down, as clear as possible; with a small address, it would be better for any one either to fix it or to take it with him or herself. As many people do not really want to be closer to the poster, a specific font size must be used. Therefore, condom posters have to be assigned in a way that they would be eye-catching and noticeable for everyone in at least two meters away from that poster. The condom use message in a poster should be designed in a form of humour to attract more people. Humour text and colourfulness are the most important designs that could stick in people’s heads. An attractive short title containing the world “condom” is an important item. Not only that poorly designed condom posters could not be well received by people, but also they could be defaced or removed by people themselves. The well designed condom posters have to be also well located according to the population villages.

Two types of locations must be considered when placing condom posters: general locations and specific locations within the EAC countries. Both of them have effect on the appropriateness and effectiveness of the condom poster location. General locations are places where people spend most of the time. For example, condom posters should be located in schools and colleges, youth clubs and centers, cafes and fast-food restaurants, shopping centers, bars, pubs and nightclubs, leisure and sports centers (Egger et al.2000). However, some of the mentioned locations may not agree to display condom posters. As most of youth clubs and centres in EAC are funded by religions, which could not allow condom posters, in this case the church representatives in those locations can take down condom posters.

The specific locations may include the general waiting locations like doctors’ and dentists’ waiting rooms, bus stations, bus shelters, toilets and changing rooms, hairdressers and barbers. These are mostly places where people sit and wait, which may cause them to look around (Gilmour, Gilmuor, Karim and Fourie, 2000). While people are waiting, they get enough time for just reading condom posters all around. The specific placement of the condom posters with any EAC country should fit one of these criteria: being a most popular location, being a place where people wait, generally places where people are forced to look at posters. For example, doors and room entrances of public buildings would fit those criteria. The most used corridors, like the way to dining room in school and colleges, are the best popular locations for condom posters. Most of the time it would be better to put the condom posters in a corridor that is not too busy. The key to promoting condom using posters is to place them at as many appropriate locations as possible. As it would be not inevitable for some condom posters to be destroyed or replaced, so it is better to check as many times as possible if there are some posters which need to be replaced. Sexual health professionals are needed to visit schools and colleges to talk about condom use.

Visiting speakers can help people in youth clubs and teenager schools to choose using condom, of course by the impression the visiting speaker makes. In order to transmit the full message, visiting speakers must be friendly, approachable and understandable. To be more successful, again leaflets and booklets must be given to the participants during a visit. These could include enough information about condom use and, equally important, information about price and its local availability.

Leaflets and flyers are used when people wish to get more specific information about the condom use. The language should be understandable. Both condom images and its colour should be eye-catching on leaflets. It would be useful again for leaflets to contain clear condom use illustrations. Leaflet design could even take the condom shape in order to attract more people. As with posters, the locations should be the ones where anyone can pick leaflets and flyers confidentially. There are two ways by which this can be done.

First of all, leaflets or flyers may be given to everyone. This could be achieved by:

- Giving leaflets to everyone during each class of sex education or after a talk from a visiting speaker;

- Including both leaflets and flyers in newspapers and magazines;

- Handing and distributing either flyers or leaflets at youth special events or outside the bars and clubs;

- Distributing them door to door by mail.

Secondarily, flyers and leaflets can be left and kept in an appropriate place where people can come and pick any of them secretly. Those places include schools and colleges, libraries and waiting rooms of doctors and dentists. Doctors’ and dentists’ waiting rooms could be the most suitable places as people may be waiting and more likely could therefore pick a leaflet or flyer and read it (Karahé, Abraham, Scheinberger and Olwig, 2005). After the use of leaflets and flyers as means to promote condom use, then comes the use of magazines and newspapers.

Generally, women’s magazines in EAC are an important source of information because of the adverts and articles they contain addressing sexual health promotion. The information they contain can engage people into discussion and therefore think about sexual health. Apart from women’s magazines, there are local newspapers in each community country. These could be better to advertise condom use in local villages. The local newspapers appear to be read by men than women. The importance of these newspapers to promote condom use is based on their free circulation. The best pages to place condom use advertisement are the ones after the entertainment section and the sports section, because those are the ones that mostly attract people. Music and sport magazines could also play a crucial role; they are the mostly read publications among youth population. The popularity of radio and television make them also to be very useful to transmit the condom use message (Randolph and Viswanath, 2004). This could try to influence the population environment and behaviours so that it could be more supportive for condom use.

It is true that radios are listened in homes, cars and workplaces. As condom use adverts through television and radio could be limited by available time, the transmitted message should be somehow short, sharp, humorous and accompanied by a popular music that could attract a high number of young people (Escar-Showes et.al. 2005). The chosen radio and television stations must be local and popular among the population. The suitable time periods per day or week suggested to condom use adverts include:

- In morning prior to school;

- After school time hours;

- Later in the evenings; early evenings on Friday and Saturday when people are getting ready to go out.

In addition, condom use adverts on radio or television should be transmitted before or after the most popular programmes. Other events are important to promote the condom use, like visits, open days and special annual world events.

Visits and open days are essentials to transmit the condom use messages either by leaflets and flyers or by condom talks. Special events like the world AIDS day celebration are also helpful as participants will be given leaflets and, why not, condoms. This is to be effective: those special events festivals could invite some local famous and popular people, like musicians, to help promoting condom use on that particular day (Wolf and Bond, 2002).

Tickets, calling cards, freebies like biro pens, key-rings and computer mouse pads could be designed with the name and phone number of the nearest condom promoting center. Tickets can transmit the promotional condom message already printed on their back. Cinema, music or bus tickets can be used.

Conclusively, as a formal intervention, condom use promotion in East African Community will be evaluated to ensure its successful effects.

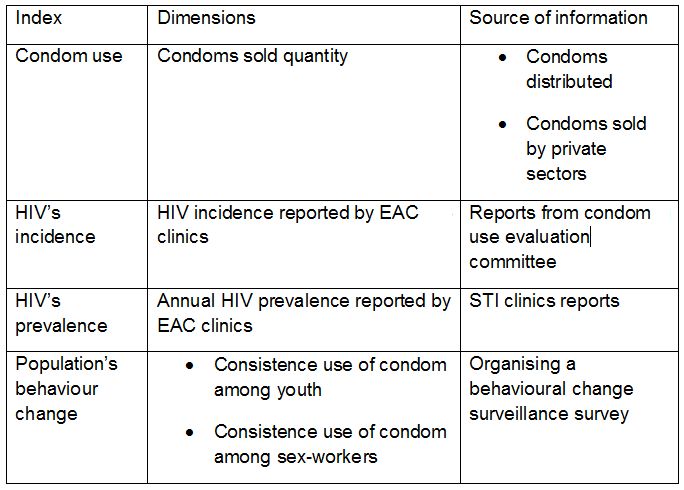

The following are several parameters which should be considered at the time of evaluating the effectiveness of the particular mentioned condom use intervention in EAC:

Table 1: Indicators to evaluate the intervention.

According to each and every EAC country’s HIV/AIDS status, HIV has been seemingly persistent, and insistence on the use of condom could be the only effective intervention against HIV/AIDS transmission in the region. This intervention should target common risk factors and most at risk population described above within all EAC countries. The fact that there are still misconceptions and myths which negatively impact condom use promotion is the reason why providing information regarding condom use is still a challenge. It is necessary that condom use intervention is not blocked by various people’ religious and cultural values. This draws evidence from a range of country level HIV status and condom use misconceptions to argue the usefulness of condom promotion in EAC to prevent HIV transmission. Condom use is a fundamental weapon to prevent HIV epidemic, as prevention is always better than treatment.

References

1. Akwala, P. Madise, N. Hinde, A. 2003. Perception of risk of HIV/Aids and Sexual behaviour in Kenya. Journal of biosocial science, 35 (3), pp.385-441.

2. Alta,

C.D. 2008. HIVAIDS Care and counseling. 4th

ed.

[E-book]

Cape Town: Pearson.

3. Brieger WR et al. (2001). West African youth initiative: outcome of a reproductive health education program.

Journal

of Adolescent Health,

29:436–446.

4. Cohen D., Scribner, R., Bedino, R. and Farley, T. 1999. Cost as a barrier to

condom use: The evidence for condom subsidies in the united states.

American journal of public health, 98(4), pp.567-568.

5. Condom Use in Rwanda Hampered By Stigma, Unavailability In Remote Areas, Officials Say. HIV/AIDS News. FIND ONLINE

6. David

W. 2006. HIV epidemiology: A review of recent trends and lessons.

World bank.USA.pp.9.

7. EAC (East African

Community), 2007.

EAC

Regional integrated multisectoral HIV and Aids strategic plan

2007-2012. Arusha, Tanzania 24th -27th

September 2007. [Pdf] Arusha: EAC Secretariat. pp. 8.

8. EAC, 2009. East Africa Community HIV Prevention Experts Think Tank Meeting Rwanda Country Presentation. Nairobi, Kenya 24th-25th February 2009.

9. EAC (East

African Community), 2009. East

African

Community Regional HIV Prevention Experts Think Tank and

Multisectoral Stakeholders Meeting. Nairobi, Kenya 24th

– 25th

February 2009. pp. 4-6.

10. EAC, 2009. Epidemic

situation and national response for prevention in Burundi, presented

during the EAC regional HIV prevention experts think tank meeting.

Nairobi, Kenya 24th-25th

February 2009.

11. EAC, 2009. HIV prevention

priorities in high prevalence epidemics: an overview. [Pdf] Arusha:

EAC secretariat.

12. EAC,

2009. Status of HIV in Kenya, presented during the EAC regional HIV

prevention experts think tank meeting. Nairobi, Kenya 24th-25th

February 2009.

13. Edward, C. 2003. Rethinking AIDS Prevention: Learning from successes in developing

countries. Praeger publishers.pp.101.

14. Egger,M.,et

al. 2002. Promotion of condom use in a high-risk setting in nicaragwa:

a randomised control trial. The lancet, 355(9221),pp 2101-2105.

15. Ezekiel,

K. Susan, C., Joseph, R.and Jayati, G. 2004. HIV and AIDS: beyond

epidemiology. [E-book] Oxford: Blackwell publishing Ltd. pp.177.

16. Escobar-Chaves, S.L.,

et.al. 2005. Impact of the media on adolescent sexual attitudes and

behaviours. Paediatrics, 116 (1), pp. 303-326.

18. GAO,

2001. Global

Health: U.S Agency for international government Fights AIDS in

Africa, but better data needed to measure impact. [Pdf]: GAO. pp.21.

19. Gilmuor, E., Karim, S. S., Fourie, J. 2000. Availability

of condoms in urban and rural areas of Kwazulu-Natal. Sexually

transmitted diseases, 27(6), pp.353-357.

20. Gray, R.et

al. 2006. Uganda’s HIV prevention success: The role of sexual

behaviour change and the national response. Commentary on Green et

al. (2006). AIDS behaviour. 10 (4):347-350.

21. Hausser,

D., 1993. The Aids problem in Burundi and its prevention among young

people. Sozial-und proventiomedizin, 36 (6), pp. 398-400

22. AVERT. HIV and AIDS in Uganda. FIND ONLINE

23. AVERT. AIDS and HIV Around the World. FIND ONLINE

24. Human Rights Watch.

2004. Access to condoms and HIV/AIDS information: A Global Health and

Human Rights Concern. [Pdf]: Human Rights Watch pp.27.

24. Ingham,

R., Aggreton, P. 2006. Promoting young people’s sexual health.

International Ltd.

25. Krahé, B., Abraham, C., Scheinberger

Olwig, R. 2005. Can safer-sex promotion leaflets change cognitive

antecedents of condom use? An experimental evaluation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 10(2), pp.203-220.

26. Laura,

G. et.al. 1999. Preventing HIV in developing countries, biomedical and behavioral approaches. New york: Kluwer

academic/Plenum publishers. pp.241.

27. Logfield,K., Glick,A., Waithaka, M.,Berman, J. 2003.

Cross-Generational

Relationships in Kenya: Couples’ Motivations, Risk Perception for

STIs/HIV and Condom Use. [Pdf] AIDSMARK. pp.18.

28. Mariangela,

F and Ina, D. 2005. Impact of interventions promoting condom use among

HIV-infected individuals. Revista de saúde pública, 39 (2).

29. Marston, C. 2004.

Gendered communication among young people in Mexico: Implications for

sexual health interventions. Social science and medicine, 59 (1),

445-456.

30. Mitchell, K., Nakamanya,S., Kamali,

A. and Whitworth, J. 2001. Community-based HIV/AIDS education in rural

Uganda: Which channel is most effective? Health education research,

16(4), pp.411-423.

31. PlusNews. Global HIV/AIDS news and analysis: RWANDA: New campaign to boost condom use. FIND ONLINE

32. Randolph, W. and

Viswanath, K. 2004. Lessons learnt from public health mass media

campaigns: Marketing health in a crowded media world. Annual review

of public health, 25, 419-437.

33. Renaud,

C., Angelina B., Mary, K. Kyle, J., Elizabeth, M. 2009. The free

condom initiative: Promoting condom availability and use in New York

City. Public health reports, 124(4), pp.481-489.

34. Shane,

K. and Vinod M. 2008. Youth Reproductive and Sexual Health. DHS Comparative Reports No. 19 .Calverton:

ICF Macro.

35. Shorter,

A. 2004. East African Societies. [E-book ] London:

Routledge Ltd.pp.149.

35. St. Lawrence JS, Scott CP. (1996). Examination of the relationship between African-American adolescents’

condom use at sexual onset and later sexual behaviour: Implications for condom

distribution programs. AIDS

Education and Prevention,

8(3), pp. 258–266.

36. UNAIDS. 2004. Making

condoms work for HIV prevention. Geneva: UNAIDS.

37. UNAIDS. 2003. Peer

education kit for uniformed services. Geneva: UNAIDS.

38. UNAIDS. 2006. Report on the global AIDS epidemic: Executive summary. pp.11.

39. UNAIDS,

2006. Report on the global Aids epidemic: Progress in Countries.

[Online]

pp.

66.

40. USAID. 2002. What

happened in Uganda? Declining HIV prevalence, behaviour change, and

the national response. Calverton: DHS.

41. USAID,

2008. Men’s condom use in higher-risk sex: Trends and determinants

in five sub-Saharan countries. Calverton: DHS.

42. Waithaka,

M.Bessinger, R.2001. Sexual behaviour and condom use in the context of

HIV prevention in Kenya. [Pdf] USAID, USA. pp. 12-19.

43. WHO. 2001. Controlling STI

and HIV in Cambodia: The success of condom promotion. Geneva: WHO.

44. WHO. 2004. Global

consultation on the health services response to the prevention and

case of HIV/AIDS among young people. Geneva: WHO

45. WHO. 2004. Protecting young

people from HIV and AIDS: The role of health services. Geneva: WHO.

46. William,

N., 1999. Power in the blood: a handbook on AIDS, politics, and

communication. Routledge, UK. pp. 150-159.

47. Wolf, C. and Bond, K. 2002. Exploring the similarity between peer educators and their contacts and AIDS-protective behaviours in reproductive health programmes from adolescents and young adults in Ghana. Aids care, 14(3), pp. 367-373.

Cite this paper

APA

Rutanga, J. P. (2013). Evidence of promoting the use of condom as a public health intervention to prevent HIV transmission in East African Community region. Open Science Repository Sociology, Online(open-access), e70081921. doi:10.7392/Sociology.70081921

MLA

Rutanga, Jean Pierre. “Evidence of Promoting the Use of Condom as a Public Health Intervention to Prevent HIV Transmission in East African Community Region.” Open Science Repository Sociology Online.open-access (2013): e70081921..

Chicago

Rutanga, Jean Pierre. “Evidence of Promoting the Use of Condom as a Public Health Intervention to Prevent HIV Transmission in East African Community Region.” Open Science Repository Sociology Online, no. open-access (April 29, 2013): e70081921. http://www.open-science-repository.com/evidence-of-promoting-the-use-of-condom-as-a-public-health-intervention-to-prevent-hiv.html.

Harvard

Rutanga, J.P., 2013. Evidence of promoting the use of condom as a public health intervention to prevent HIV transmission in East African Community region. Open Science Repository Sociology, Online(open-access), p.e70081921. Available at: http://www.open-science-repository.com/evidence-of-promoting-the-use-of-condom-as-a-public-health-intervention-to-prevent-hiv.html.

Nature

1. Rutanga, J. P. Evidence of promoting the use of condom as a public health intervention to prevent HIV transmission in East African Community region. Open Science Repository Sociology Online, e70081921 (2013).

Science

1. J. P. Rutanga, Evidence of promoting the use of condom as a public health intervention to prevent HIV transmission in East African Community region, Open Science Repository Sociology Online, e70081921 (2013).

doi

Research registered in the DOI resolution system as: 10.7392/Sociology.70081921.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.