Open Science Repository Public Administration

doi: 10.7392/openaccess.70081957

Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government

Faculty of Business and Development Studies, Gulu University, Uganda

Abstract

Understanding what explains budget performance and credibility in local government (LG) is becoming an increasingly contentious and managerial concern in recently decentralized countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. This study draws from two separate but closely related philosophical underpinning, namely the fiscal federalism theory and fiscal illusion theory, to create understandability of operational antecedents of LG budget performance in such economies. The rationale is to examine linkages between central government patronage (the perceived source of budget performance) and budget performance. The research also lends consideration to the mediating role of entity autonomy in that relationship. Results from a survey of 217 administrators and employees drawn from 18 districts in Uganda indicate that central government patronage positively influences budget performance when mediated by entity autonomy. The findings are discussed with respect to theoretical, empirical and practical implications for LG budgetary activity and performance.

Keywords: local government, budget performance, central government patronage.

Citation: Onyango-Delewa, P. (2013). Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government. Open Science Repository Public Administration, Online(open-access), e70081957. doi:10.7392/openaccess.70081957

Received: April 22, 2013

Published: May 4, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Onyango-Delewa, P. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Contact: [email protected]

Introduction

Budget performance is increasingly becoming a significant concern for local governments (LGs) as a basis of executing their resource allocation mandate and ensuring effective service delivery at the grassroot level. LGs, especially those in resource-constrained economies across Sub-Saharan Africa, are required to create and preserve capacity (Auclair, 2002, Awio & Northcott, 2001). They are also obliged to observe relevant budgetary institutions (Botner, 1985; Braun & Grote, 2000) and comply with donor aid conditionalities (Brosio, 2000; Gabor Soos, 2001) in order to attain the above constitutional objectives.

The question of budget performance in local government is operationalized from various perspectives. Its key antecedents have commonly linked it to fiscal conservatism (Hoffmann & Gibson, 2005), debt minimization (Moon & Williamson, 2010; Rondelli, 1981) and bail-out susceptibility (Ndegwa, 2002; Shah, 2003; Smoke, 2001). The antecedents draw their empirical strength from the fact that fiscal conservatism, also referred to as budget discipline, debt management, and bail-out indicators constitute the hallmark of budgetary performance in such entities (Dafflon, 2000; Degefa, 2003; Kukkiriza, 2007). Literary, the underlying fundamental question is: Why do LG annual revenue receipts and expenditures continually digress from planned structures (the budget)?

The dominant position in fiscal federalism literature; the policy and theoretical domain governing LG budgeting, often addresses it through the concepts of financial planning and donor aid (e.g. Alesina & Perotti, 1996; Fjeldstad Odd-Heldge, 2001). The conventional knowledge is that, once realism and accuracy are attained when setting budget estimates and forecasts (effective financial planning), budget performance competency is created (J’onsson, 1982; Kloot & Martin, 1999).

Another stream of literature (e.g. Lister & Betley, 1999; Obwona, Steffensen, Trollegaard, Mwanga, Luwangwa, Twodo, Ojoo & Seguya, 2000; Schacter, 2005) attributes LG budget performance in Sub-Saharan Africa to the donor aid factor.

The influence of central government patronage on LG budgeting and performance has received little attention in previous fiscal federalism research despite the foundational role played by central government on decentralization policy of the state. As Borck and Owing (2003), Litvack, Junaid and Bird (1998) and Tanzi (1995) argue, through inter-governmental transfers (grants) central government engenders wide powers to patronize local government operations. In countries like Uganda (DFID, 2006; Wasswa-Katono; World Bank, 2004), Ghana (Brosio, 2000; Larbi, 1999), and Ethopia (Eshetu Chole, 1994; Keller, 2002), for instance, conditional, unconditional and equalization grants significantly impact LG budgets. Scholars like Kyobe and Dillinger (2005) and Obwona et al. (2000) have also demonstrated that budgetary guidelines, policies and law (institutionalization) relate closely with sub-national entity budget performance. External audits and scrutiny undertaken on LG financial activities and related fiscal concerns by the central government agencies strengthen internal controls and cultivate accountability and transparency (Shleifer, 1998; Von Hagen & Eichengreen, 1996).

The three antecedents of central government patronage, namely grants, institutionalization and audit and external scrutiny, identified in empirical studies have over the years been examined to explain changes in local government budget performance, but as stand-alone constructs.

Our goal is therefore to examine the contextual central government patronage antecedents above and create understandability of how they may influence LG budget performance when acting interactively. As a point of departure, this research also examines entity autonomy as a probable mediating factor between central government patronage and budget performance.

More recent research (e.g. Moon & Williamson, 2010; Mugerwa & Juuko, 2010; Smoke, 2001; Shah, 2003) argue that keeping entity autonomy at the analysis periphery undermines efforts to localize budget performance setbacks and impair service delivery in African sub-national units.

To understand how grants, institutionalization and audit dimensions can generate performance in LG budgets, we combine two theoretical frameworks: fiscal federalism theory and fiscal illusion theory. Our core proposition is that the two frameworks jointly describe the patronage relationships that central government rests upon to create budget credibility in local government.

Theoretical review and hypothesis development

Since the advent of the new public management (NPM) philosophy (Aucoin, 1990; Brignall & Modell, 2000; Larbi, 1999; Oates, 2001), empirical research has been embroiled in figuring out the most optimal approach to efficient, effective and economic model of resource allocation. Hammond and Knott (1999) and Osborne and Gaebler (1992) observe that public choice, one of the key tenets of NPM, requires fiscal decentralization mechanisms built on market-based and competition-guided principles for effective public resource management.

Although contested in several empirical circles such as the new public service (NPS) model (Denhardt & Denhardt, 1999, 2000), the NPM formation engenders important philosophical underpinnings such as fiscal federalism theory (Cremer, Estache & Seabright, 1996; Dafflon, 2000; Fjeldstad Odd-Heldge, 2001) and fiscal illusion theory (Alesina & Perotti, 1996; Hudson & GOVNET, 2009). These significantly guide service delivery efforts in sub-national entities.

Fiscal federalism theory, fiscal illusion theory, and the link between central government patronage and the performance of the local government budget

The growth in the number of countries embracing decentralization as a form of governance has spurred increasing interest in associated topical areas of fiscal resource allocation and distribution literature (Bevir, Rhodes & Weller, 2003; Oates, 2001). Notable among them is the concept of fiscal federalism (decentralization). When the control and management of fiscal resources is assigned to sub-national entities, it is thought to generate allocation efficiency and local community sense of ownership which eventually culminates into satisfactory service delivery. In this respect, Braun and Grote (2000), Brosio (2000) and Conforti, de Muro and Salvatici (1998) report strong relationship between fiscal federalism and service delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fiscal federalism is, however, a policy decision by central government as an offshoot of the entire decentralization package (Covaleski & Dirsmith, 1986; Gershberg, 1998). What underscores its notion is the implied and underlying reality that the state has a big stake in its sustainability; what extant literature (e.g. MacReynold & Fuhrer, 2002; Wibbels, 2000) considers a manifestation of central government patronage. In politically-driven grassroot level resource allocation and agency institutions local governments of Africa, central government patronage is believed to significantly influence the affairs of the budget and how it should perform (Garson, 2007; Ribot, 2002).

The fiscal federalism theory (Botner, 1985; Feng, 2005; Islam, 2009) is characterized by the proposition that decentralizing public resource allocation empowers local authorities to act responsibly, creates ownership sense in the masses and ultimately leads to service satisfaction. As the central government is decongested, some authors (Degefa, 2003; Lister & Betley, 1999; Mugerwa et al., 2007) claim that it gives room for effective patronage in form of clear grant management and supervision, institutional monitoring, and conducting of reliable audits.

Key research (e.g. Conforti et al., 1998; Fjeldstad, 2001; Litvack et al., 1998) emphasizes the need for the decentralization framework to continually create working links between local financing and authority to service provision and LG functionality. Litvack et al., in particular, believe that such a stand would make local political leadership appreciate their decision costs, account for such costs,and live by their commitments. Several studies have also confirmed the hypothesis that grants allocated to LGs on equity basis and tailored to local operational circumstances create budget discipline, reduce entity indebtedness and curtail bail-out vulnerability. The works of Kundishora (2004), McGill (2001) and Ndegwa (2002) reveal grant allocation mechanisms for sub-national entities dictated by central government.

The approach not only demoralizes LG managerial commitment but creates laxity in conservatism efforts. This leads to misappropriations, debt, and need for supplementary budget bail-out (Oates, 1999; Shah, 2003; Tanzi, 1995).

Closely related to the issue of grants (inter-governmental transfers) is budgetary institutionalization. Like the national budget, sub-national budgets and work plans must be prepared and implemented in accordance to some guidelines, regulation and statutes (McCleary, 1991; Von Hagen & Eichengreen, 1996; Wasswa-Katono, 2007).

The fiscal federalism theory posits that institutionalization is a conducive vehicle for propelling central government patronage to impact budget performance. However, some studies (e.g. Moon & Williamson, 2010) caution against rigid institutions tendency to frustrate compliance efforts and generate negative effects to LG budgeting. Some prior research works (e.g. Rondelli, 1981; Roubini & Sachs, 1989; Schacter, 2005) advice that budget institutions must be flexible and comprehensive enough to capture other budgetary dimensions like estimation and forecasting and donor aid relations.

Based on the foregoing conceptual and theoretical logic in regard to budget performance in local government, we therefore propose the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: There is a direct and positive relationship between inter-governmental transfers (grants) and budget performance.

- Hypothesis 2: Budgetary institutionalization is positively associated with budget performance.

Many authors have also highlighted the role played by external audit and scrutiny in LG financial and the budgetary systems as a pre-requisite for attaining budget credibility (Awio & Northcott, 2001; Lister & Betley, 1999; Lynn, Heinrich & Hill, 2000). Fiscal illusion theory (Fjeldstad, 2001; Winer, 1980) proposes increased sub-national autonomy to mitigate eminent fiscal imbalances that often derail resource allocation in those units. The audits enhance entity autonomy, create a sense of resource ownership and engender budget efficiency (Winer, 1980).

Degefa (2003) and Ndegwa (2002) identify vertical fiscal imbalance (VFI), the measure of the degree of control exercised by central government over lower levels of government, as one of the most distracting phenomena to LG budget efficiency. Several other Sub-Saharan Africa-based studies (e.g. Keller, 2002; Shah, 2003; Smoke, 2001; Uganda Debt Network, 2006; World Bank, 2004) attribute VFI to inadequate LG tax administration capacity. This prompts adoption of resource centralization policies in many governments. It has also been noticed that lack of adequate autonomy undermines LG ability to generate sufficient local revenue required to match their spending needs (Conforti et al., 1998; Smoke, 2001).

Related to vertical fiscal imbalance is horizontal fiscal imbalance. A fundamental stance in this aspect is economic inequality among different sub-national (LG) entities apparently driven by weak grant allocation approaches. Brosio (2000) and Caiden (1996) suggest that allocations should be made based on realistic yardsticks such as population structure and level of economic development.

Partisan political influences should not be allowed to influence the allocation formulas. External audits and scrutiny have therefore been found necessary tool not only for strengthening internal audit functions, but also as a means of checking fiscal imbalances and augmenting LG autonomy. Literature recommends that the audits be carried out by a central government ombudsman. In Uganda, the Auditor General is the external audit authority (DFID, 2006; Obwona et al., 2001; Wasswa-Katono, 2007). Addressing fiscal imbalance practices and creating adequate resource management discretion creates budgetary performance and credibility in local governments (Kyobe & Dillinger, 2005; Mugerwa et al., 2007; Moon & Williamson, 2010). The above theoretical discourse leads to the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 3: External audit and scrutiny positively relates with budget performance.

- Hypothesis 4a: Entity autonomy will mediate the relationship between inter-government transfers (grants) and budget performance.

- Hypothesis 4b: Entity autonomy will mediate the relationship between institutionalization practices and budget performance.

- Hypothesis 4c: Entity autonomy will mediate the relationship between external audit and scrutiny practices and budget performance.

- Hypothesis 4d: Entity autonomy will mediate the relationship between central government patronage and budget performance.

Empirical study sample, measures and methods

We tested our hypotheses using data collected through a structured interview guide and a survey from district administrators and employees and central government officials in Uganda, East Africa. Uganda is considered a role model in the decentralization system of governance in Sub-Saharan Africa (DFID, 2006; Kisembo, 2006; Livingstone & Charlton, 2001).

Currently, the country runs an elaborate fiscal decentralization policy operated under 112 districts (Fountain Publishers, 2012; MoLG, 2012). Obwona et al. (2000) and Uganda Debt Network (2006) found the district as the most elaborate local government (LG) in Uganda mandated with full constitutional powers to allocate fiscal resources at the grassroot level.

Consequently, districts are obliged to produce balanced, performing and credible annual budgets (Awio & Northcott, 2001; Kukkiriza, 2007; Kundishora, 2004; World Bank, 2004).

We interviewed Resident District Commissioners (RDCs), Chief Administrative officers (CAOs) and Local Council Five (LC5) chairpersons. Commissioner for Budget and Evaluation at the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED) and Commissioner for Planning and Policy at the Ministry of Local Government (MoLG) were interviewed at the central government level.

MoLG and MoFPED are the two line ministries directly responsible for fiscal decentralization and local government budgetary activity (MoLG, 2012; MoFPED, 2012).

Questionnaires were mailed to district budget desk officials, namely chief finance officer (CFO), district planner/statistician, procurement officer and internal auditor. Other participants were staff working directly under the above officials. The officials purposively hand-picked such employees for the exercise. The survey was carried out between March 2012 and November 2012 within 18 districts located in north-western, northern, north-eastern and eastern Uganda as part of a doctoral research pilot scheme. The districts are: Yumbe, Koboko, Arua, Nebbi, Amuru, Kaabong, Kapchorwa, Manafwa, Bududa, Budaka, Butaleja, Namutumba, Kaliro, Amuria, Bukedea, Nwoya, Dokolo and Amolatar (Fountain Publishers, 2012; MoLG, 2012; MoFPED, 2012).

They constitute the category which has been in existence for between five and nine years. Prior studies (e.g. Moon & Williamson, 2010; Mugerwa et al., 2007; Wasswa-Katono, 2007) associate this group of LGs in Uganda with a substantial body of budgetary data and experience.

A total of 252 questionnaires was dispatched to prospective participants. The participants were informed that their involvement in the study is voluntary and that their responses are strictly anonymous (Miller, 1983; Oppenheim, 1992; Rubin & Babbie, 2005). Out of that lot, 224 valid questionnaires were received back providing a response rate of 89%. A number of empirical studies (e.g. Armstrong & Overton, 1977; Oppenheim, 1992) claims that high response rates, that is, 60% and above, signify minimal threat of non-response bias in behavioural and social science studies.

After eliminating a few cases due to missing data, unclear and contradictory responses, 217 questionnaires were used in the final analysis. The survey reveals that 73% of the respondents were male, 54% of them married. They were of a mean age 32.6 years (SD 8.26), and an average 5.27 years of tenure in office (SD 1.009). Most of them (82%) held qualifications higher than a bachelors degree. The demographics of the piloted LGs did not differ significantly from each other.

Measures

The survey instrument included psychometric scales designed to measure the variables budget performance, central government patronage and entity autonomy and their constructs. Each of the multi-item measures was based on a five-point Likert scale with anchors 1(strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree). Most of the constructs were measured by scales previously tested in the literature (e.g. Brosio, 2000; Livingstone & Charlton, 2001; McGill, 2001; Smoke, 2001).

Budget performance

Budget performance, the study dependent variable, was operationalized by three constructs: fiscal conservatism, deficit minimization, and bail-out susceptibility. Modified scales developed and recommended as fiscal transparency best practices by the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2000) and those used in various empirical works were employed as measures.

For instance, fiscal conservatism comprised 40 items some of which reverse-coded (Castro, 2002; Oppenheim, 1992) were measured by scales developed by Litvack and Bird (1998) and Tanzi (1995). Sample items include: “receipt and expenditure records adhere to approved budget principles; Council does not approve supplementary budgets” (α=.239). Deficit minimization was measured by 20 items based on IMF (2000) but adjusted scales. Sample item: “the LG carries out full domestic debt validation assessment”, (α=.553). The construct bail-out susceptibility was measured using a 15-item scale adopted from Gershberg (1998).The items included statements such as “bail-outs in this LG involves seeking funding from loans and guarantees from banking institutions”, (α=.569). As a whole, budget performance exhibited internal consistence reliability (α=.559).

Central government patronage

Based on extant literature, this variable was operationalized by the level of inter-governmental transfers (grants), institutionalization and audit and external scrutiny. The survey carried 33 items regarding grant activities one of which was: “grants released to this LG are always adequate for its operations”. The works of Fjeldstedt, 2001, and Livingstone & Charlton, 2001 revised scales that exhibited a consistence (α=.682). To operationalize institutionalization, we asked LG budget desk officials and employees to indicate the extent to which they consider budgetary guidelines and regulation affect budget performance. Most of the statement items were drawn from Obwona et al. (2000) and Von Hagen and Eischengreen (1996). The Cronbach alpha value for the construct was α=.691. Statements similar to those in the work of McReynold and Fuhrer (2002), Schacter (2005) and Winer (1980) were employed in assessing audit and scrutiny construct. Its reliability index value was α=.655.

Entity autonomy

To operationalize entity autonomy we asked participants to indicate its possibility of mediating between the study independent variables and budget performance. 16 statements developed in line with past research (e.g. Islam, 2009; Mugerwa et al., 2007) included items such as: “this LG is already independent and autonomous in fiscal terms”. Alpha (α=.753) was generated.

Once scaled, central government patronage, entity autonomy and budget performance constructs (Table 1) exhibited on average acceptable levels of internal reliability with coefficient alpha ranging from α=.721 to α=.843. Research works (e.g. Cortina, 1993; Field, 2005; Nunnally, 1978) recommend α=.700 as an ideal threshold. However, those pertaining to budget performance (α=.239) was below the α=.700 threshold.

We also conducted property psychometric screening for the various measures used in the study. This is relevant in order to confirm the tenability of their parametric assumptions (Hair et al., 1998; Nunnally, 1978). Key tests include normality, linearity and homoscedasticity, and multi-collinearity (Kozlowsky & Klein, 2000).

Nunnally (1978) and Swailes (2002) delineate normality assessment to two criteria: graphical and computational approaches. Normal probability, scatter boxes and histograms are key conventional graphics. Since both methods engender similar results, we opted for kurtosis and skewness statistics-based computations (Satorra & Bentler, 1988). The data exhibit normality since both skewness and kurtosis output meet the 2.5 times their respective standard errors threshold (Jaccard et al., 1990; Satorra & Bentler, 1988).

In most social sciences research, hypotheses are tested using regression analysis while correlation tests examine variable and construct associations. The two measures involve capturing only linear identities (Castro, 2002; James, Demaree & Wolf, 1993). Our residual plots exhibited a number of residuals scattered around the zero points and later showing signs of ovality. Such findings suggest a strong feature of linearity and homoscedasticity presence (Armstrong & Overton, 1977; Nunnally, 1978).

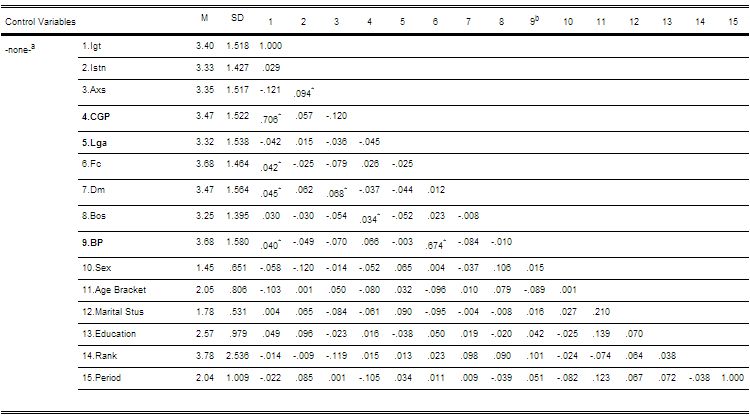

When independent variables and constructs are closely associated, they influence hypotheses results unfavorably (James et al., 1993; Hoffmann & Garvin, 1998). Multi-collinearity, the resultant phenomenon, is assumed non-existent when their: correlations (r) are less than 0.700 (Nunnally, 1978; Wanous & Reichers, 1997); Durbin-Watson regression-based statistic is below 2.000 (Belsey et al., 1980; Cortina, 1993); and their collinearity tolerance and variance inflation factors (VIFs) are less than 1.000 and 10.000 respectively (Eisenhardt, 1998; Field, 2005). Zero-order correlation (Table1) and Durbin-Watson (1.743) in the hierarchical regression analysis (Table 2) suggest that the above conditions had been met.

The tolerance scores for inter-governmental transfers, institutionalization and audit and external scrutiny were 1.016, 1.010 and 1.025, while their VIFs were 0.984, 0.990 and 0.976, respectively. In sum, the findings suggest that multi-collinearity was not a threat to the study.

Control variables

The institutional configurations of the different Uganda-based local governments (LGs) suggest a workforce that displays a wide range of demographic characteristics. Previous research (e.g. Fjeldstadt odd-Heldge, 2001; Kukkiriza, 2007; Kundishora, 2004; Obwona et al., 2000) find characteristics such as age, education or rank of significant influence on individual feelings towards the LG budgetary process and specifically budget credibility.

As part of the study, we therefore collected demographic data. Firstly, the data are necessary for guaranteeing respondents anonymity (Field, 2005; Yang, Wang & Su, 2006). Secondly, consistent with the theoretical assumptions (e.g. Aiken & West, 1991; Eisenhardt, 1989; Swailes, 2002), the demographic variables are controlled to rule out possible alternative explanations to the study hypotheses. Further, Swailes (2002) recommends that there is need to control for biographical characteristics in order to reduce the possibility of spurious relationships arising from socio-demographic differences in the predictor-outcome variables.

Each of them is treated as a dummy variable and measured accordingly (Eisenhardt, 1989; Swailes, 2002). Consequently, appropriate scales (e.g. gender: 1=male, 2=female) were adopted to measure and statistically control for them, since they had to be matched with ordinary responses of the questionnaire. Thirdly, some studies (e.g. Klein &Hall;, 1988; Shore, Cleveland & Goldberg, 2003) provide that demographic variables tend to influence individual behavioural patterns. Factors such as gender, age, educational status and position held need controlling for to minimize concerns about unobservable heterogeneity. Taking such steps is important for mitigating skewness in the study sample. This last point was addressed by having all the five control variables logarithm-transformed (Cortina, 1993; Swailes, 2002).

Analytical procedure

In most organizations, local governments not an exception, managers, administrators and employees tend to be nested in similar operational contexts. Empirical studies (e.g. Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Bagozzi & Phillips, 1982; Jaccard et al., 1990) argue that the propositions underlying independent observation of traditional ordinary least square (OLS) regression risk violation due to this operational commonality. Resultant data overlap and concealment due to the nesting phenomenon often culminates into standard error estimate biases (Carmines & McIver, 1981; Seidler, 1974; Wanous & Reichers, 1997). To avoid this pitfall, we opted for hierarchical linear modelling (HLM), specifically stepwise hierarchical regression analysis for our hypothesis testing. The HLM methodology is considered ideal for nested data given its specificity on the problem (Bryk & Raundenbush, 1992; Kenny et al., 1998; Osborne & Costello, 2005). Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and correlation and Tables 2 and 3 regression analyses.

Results

Social science research studies, in which self-report survey data are the most dominant, are often plagued with bias. This malaise is a great threat to validity (Belsley et al., 1980; James et al., 1982; Kozlowsky et al., 2000). We therefore conducted a number of tests to confirm internal and construct validity.

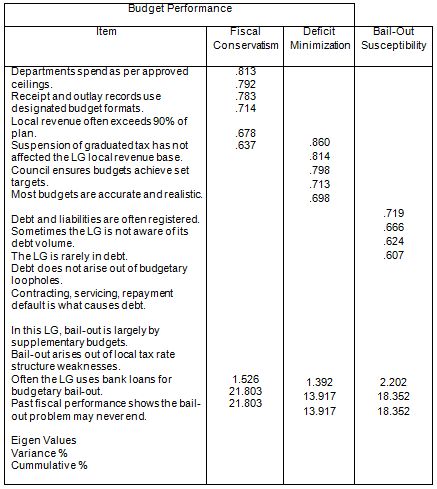

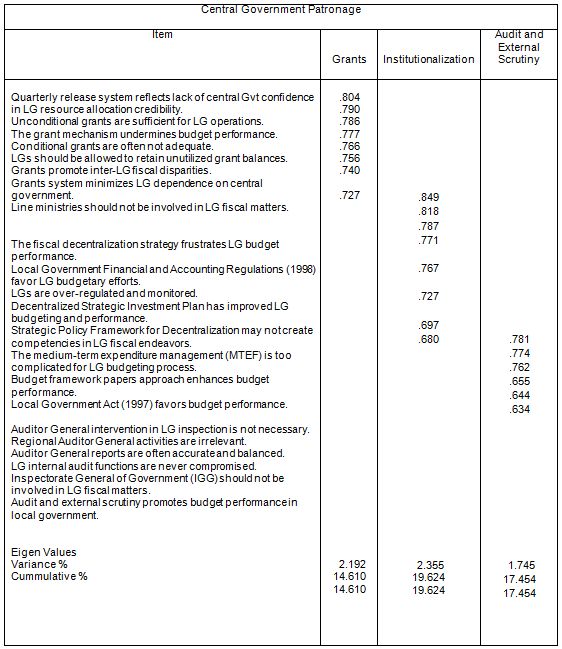

The first test was Harman’s one-factor test ideally meant to first establish the presence of any common methods variance (CMV). All variables were fed into a principle component factor analysis model with varimax rotation (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee & Podsakoff, 2003). This test yielded 22 items amongst the three constructs (grants, institutionalization, audit and external scrutiny) of the variable central government patronage (Appendix A: Table ii). All the three exhibited Eigen values greater than 1, accounting for 52% of the total variance. Budget performance, the criterion variable, yielded 15 items under its three constructs (fiscal conservatism, deficit minimization and bail-out susceptibility). Their Eigen values were also above 1 which collectively accounted for 62% of the gross variances (Appendix A: Table ii).

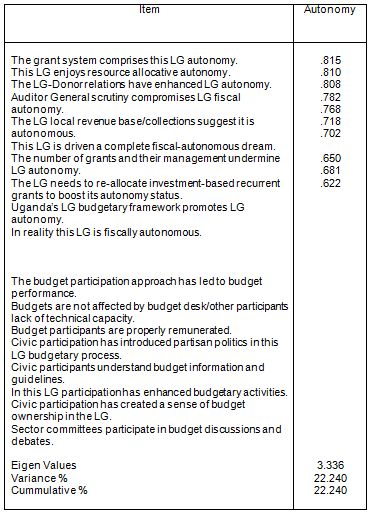

The mediating variable, entity autonomy (Appendix A: Table iii), yielded 10 items with Eigen values greater than 1 but accounting for only 22% of the total variance.

From the factor analysis results, no single factor emerged dominant. According to Podsakoff et al. (2003), such results suggest that no common methods variance problem was present.

Second, we tested the validity of budget performance, the dependent variable. Testing a criterion variable validity involves finding out, amongst other things, its dimensionality level, criterion-based validity and discriminant validity (Hair et al., 1998). Dimensionality is established through another varimax rotation-based principle components factor analysis. We obtained a three-factor solution (Appendix A: Table i) with all the items registering quite high loadings, average loading (0.730) and accounting for 54% of the total variance. Criterion-based validity was checked by examining the relationship between budget performance and other measures theoretically-related to it, namely grants, institutionalization and audit. We found significant although weak associations (r= 0.040, p < .01), (r= -0.049, p <.01) and (r= -0.070, p < .01) respectively (Table 1). The first observed correlation provides support for the proposed hypothesis (H1). The last two correlations did not secure support from the data for their respective hypotheses (H2 and H3).

The results therefore only partially supported criterion-based validity evidence for local government budget performance. Discriminant validity was assessed by examining the relationship between budget performance with theoretically-unrelated (biographical data) variables engendered from the same data source (Kenny et al., 1998; Qyen, 1990). These were control variables of gender, age, marital status, education, rank and position held. Budget performance showed positive but almost no relationship with all variables, average (r= 0.052, p < .01) (Table 1).

In sum, our results suggest that the measure budget performance has a 3-factor formation. It shows largely low correlations with theoretically related variables and almost no relationship with non-theoretically related constructs measured by the same source. Thus, we find evidence of construct validity.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and zero-order Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

Notes: a. Cells contain zero-order Pearson correlations; N=217; Igt=Inter-governmental transfers (α=.720), Istn=Institutionalization (α=.743), Axs=Audit and external scrutiny (α=.759), CGP=Central Government Patronage, Lga=Entity Autonomy (α=.738), Fc=Fiscal conservatism (α=.570), Dm=Deficit minimization (α=.641), Bos=Bail-out susceptibility (α=.597), BP=Budget Performance; Cronbach alpha (α) in parentheses; *p < .01; b. Main effect items.

Regression analysis: hypothesis testing

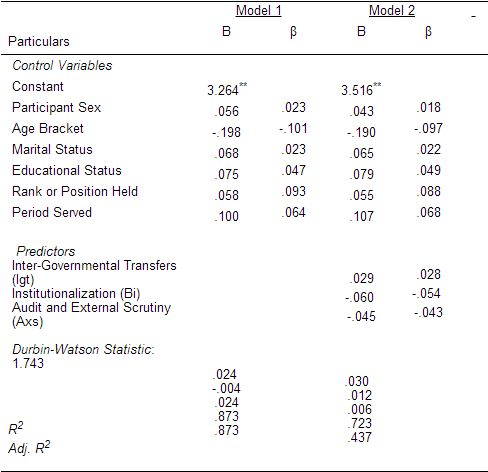

Stepwise hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted. Control variables were regressed in the first step and then followed by independent and mediating variables. The idea was to test the hypotheses and the mediation and interactive effects (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Hair et al., 1998; Jaccard et al., 1990; Baron & Kenny, 1986; MacKinnon, Fairchild & Fritz, 2007). The approach enables one to establish which predictor measures explain the most variance in the criterion factor (Jaccard et al., 1990; Kenny et al., 1998). Table 2 presents two models emanating from that regression formation within which the study hypotheses are tested.

Model 2 is the principle model and incorporates both control and main effect variables (e.g. in Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Jaccard et al., 1990). Results indicate that, when central government constructs are introduced (model 2), the gross variable accounts for only 1% (∆F= .873, p < .01) of the variance in budget performance.

Main effects

Under the variable central government patronage, we predicted as hypothesis (H1) that inter-governmental transfers will be positively related to budget performance. The results (Table 2) indicate that this proposition was supported by data (β= .028, p < .01). It had also been predicted that institutionalization, audit and external scrutiny would positively relate with budget performance as stated by hypotheses (H2) and (H3) respectively. Both hypotheses with β=.-049, p < .01, β= -.042, p < .01 scores could not secure support from the data as per the results in that table.

Table 2: Hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting budget performance (BP) from independent variable central government constructs.

Notes: **p < .01; n = 217; Regression Equation: BP = (.028*Igt - .054*Bi - .043*Axs) mediated by entity autonomy (Lga).

From the above data, a regression model based on independent variable constructs can be stated as follows: BP = (.029*Igt __ .060*Bi __ .045*Axs), where: (BP) is budget performance, (Igt) means inter-governmental transfers, (Bi) budgetary institutionalization, (Axs) is audit and external scrutiny. Entity autonomy (Lga) was posited a mediator between central government patronage and budget performance relationship.

Mediation effects (hypotheses 4a-4d)

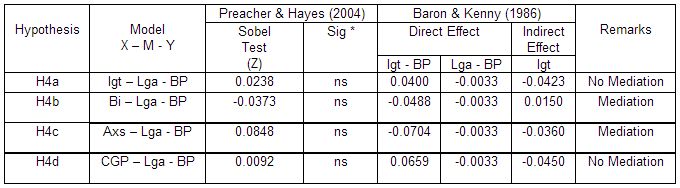

Mediation effects were tested following the generic indications by Baron and Kenny (1986). Mediation and moderation research (e.g. Preacher & Hayes, 2004; MacKinnon et al., 2007) claims that the Baron and Kenny model often leads to type 1 error. To avert this pitfall, we carried out a Sobel Test (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) as an additional assessment. Table 3 is a summary of the Sobel test and mediation effects as provided in the Baron and Kenny formation.

Baron and Kenny recommend a four-step procedure to establish whether mediation exists or not: (i) the independent variable has an effect on the dependent variable, (ii) the independent variable has an effect on the mediating variable, (iii) the mediating variable has an effect on the dependent variable, (iv) the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable becomes non-significant when the mediating variable is introduced in the regression equation. According to Preacher and Hayes (2004), mediation is considered existing when the Sobel Test’s (Z) value is (1.0) and above and significant.

Our hypothesis 4a predicts that, in the local government budgetary activities, autonomy mediates the relationship between inter-governmental transfers and budget performance. The result found for the Sobel test was (Z=0.0238, p < .01) which failed to confirm the existence of the mediation effect. We subjected this to establish the conditions necessary for mediation as proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). Firstly, there was a very weak relationship between inter-governmental transfers (Igt) and budget performance (r=.040, p < .01), and there was no effect of autonomy on budget performance (r= -.003, p < .01). Adding entity autonomy to the model lowered the importance of inter-governmental transfers (r= -.042, p < .01). Since the direct effect of (Igt) (r= .040) is greater than the indirect effect (r= -.042, p < .01), mediation effect is considered to be of little significance (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). This implies that the data do not support our proposition in (H4a).

Table 3: Regression analysis: main and mediation effects for entity autonomy on budget performance.

Notes: Igt = Inter-governmental transfers, Bi = Institutionalization, Axs = Audit and external scrutiny, Lga = Entity Autonomy, BP = Budget Performance, ns = not significant, *p < .01.

Data support (H4b) and (H4c) in which it had been predicted that entity autonomy mediates the relationships between budgetary institutionalization (Bi) and budget performance, and audit and external scrutiny (Axs) and budget performance respectively. Under (H4b), it was found Sobel test (Z= -0.0373, p < .01), while institutionalization-budget performance effect was r= -0.0488, p < .01. When autonomy is introduced in the model, the effect of institutionalization increases to r= 0.0150, p < .01, signifying a mediation effect. The Sobel test (Z= 0.0848, p < .01) and audit-budget performance effect (r= -0.0704, p < .01) were also registered. With the increase in the audit effect to r= -0.0360, p < .01, mediation is found present in conformity with hypothesis (H4c).

Our last hypothesis (H4d) could not secure expected support from the data. It was postulated that autonomy mediates the gross relationship between the variables central government patronage (CGP) and budget performance (BP). We find a Sobel test score Z= 0.0092, p < .01 and quite a low CGP-BP effect (r= 0.0659, p < .01). When the autonomy factor is brought on board, the central government patronage effect instead falls, an indication that autonomy has no mediation effect on that relationship.

Discussion

This study examines budget performance in local government in the context of central government patronage (CGP). It is based on a sample of 18 districts in Uganda. The level of district autonomy (discretion, objectivity and independence) in the fiscal resource allocation mechanism was envisioned to mediate and temper the above relationship.

In gross terms, the study independent variable, central government patronage, exhibits a strong positive association with budget performance. This finding is in line with the main stream fiscal federalism theoretical proposition (e.g. Alesina & Perotti, 1996; Auclair, 2002; Ndegwa, 2002) that sub-national budgetary efficiency resides in effective central government oversight. For this to be achieved, however, other streams of empirical thought (e.g. McGill, 2001; Obwona et al., 2000; Smoke, 2002; Tanzi, 1995) observe that it requires a backing of a strong political will coupled with civic participation.

In Uganda, for instance, the few local governments (LGs) that have managed to register high budget performance scores over the years attribute their success to disciplined budgetary behaviour and regulation commitment (DFID, 2006; Gulu District, 2009; Moon & Williamson, 2010). The challenge in attaining budgetary credibility in such institutions seems to reside in the manner individual factors underlying central government patronage, namely inter-governmental transfers (grants), institutionalization and audits, are managed.

At a micro-level consideration, it had been projected (hypotheses H1-H3) that all predictor constructs named in the foregoing section will individually positively relate with budget performance. We found that only inter-governmental transfers has a positive impact on budget performance. Institutionalization and audit and project support could not be supported by the data. The correlation analysis carried out also revealed a number of positive relationships, but these disappeared when we controlled for participant demographic characteristics during regression analyses.

In most decentralized economies of Sub-Saharan Africa, inter-governmental transfers or grants take on three forms: conditional, unconditional and equalization. This finding is compatible with government subvention literature (e.g.Von Hargen & Eichengreen, 1996; McReynold & Fuhrer, 2002; Mugerwa et al., 2007) which has demonstrated that LG budget performance improves significantly with adequate grants, remitted promptly and with less stringent application conditionalities. The grant individual nomenclature is immaterial and cannot help resource allocation efficiency in these economically poor entities, if not tailored to grassroot situations (Rondelli, 1981; Shah, 2003; Wasswa-Katono, 2007).

Empirical findings in studies such as (Jeppsson, 2001; Schacter, 2005; Smoke, 2001) also reveal that budgetary rules, guidelines and legal dispositions (collectively, institutions) have a negative effect on sub-national entity planning and budget performance.

Smoke, for instance, explicitly contends that central government authorities in decentralized systems of sub-Saharan Africa must come to terms with the practical reality that few of such institutions are fully observed. Enforcement has largely been a flop and engenders complacency to performance dysfunction. Likewise, we find institutionalization negatively correlated with budget performance. Our results and those in Jeppsson, 2001, Schacter, 2005, Smoke, 2001, however, seem to conflict with the fiscal illusion theory which defends policy budgetary guidelines (Fjeldstad, 2001; Winer, 1980). This philosophical strand assumes that resource allocation efficiency at sub-national level is a function of strong institutions (laws, regulations and guidelines) as long as they are clear and effectively enforced (Fjeldstad, 2001; Winer, 1980).

We had also hypothesized that audit and external scrutiny positively relates with budget performance. This proposition was derived from practice and empirical research (e.g. Ayee, 1994; Blondel, 2006; Degefa, 2003), which found strong performance scores in LGs whose accounting and budgetary activities are subjected to independent, objective and value-for-money audits.

Our results are astoundingly contrary in that the relationship is instead negative. The possible explanation could be that in corrupt LG systems, typical of most African LGs (Larbi, 1999; UNCDF, 2006), external audits are hardly independent and their reports tend to be compromised. This can affect the performance of the annual budgets negatively. The new public management (NPM), the principle philosophical paradigm underpinning public resource allocation and management, assumes public service delivery efficiency in environments subjected to market-like independent audits and scrutiny (Hood, 1995; Pollit, 1993; Larbi, 1999). This implies that where such independence is lacking, efficiency also lacks.

We have some noteworthy findings concerning the role entity autonomy plays as a possible mediating factor among central government patronage constructs with budget performance. Practice and empirical evidence (e.g. Islam, 2009; Gersberg, 1998; Kukkiriza, 2007; Smoke, 2001) show that local governments will operate more effectively if allowed adequate autonomy and flexibility in budgetary execution. This position is echoed in the fiscal illusion theory (Fjeldstad, 2001; Winer, 1980) which advocates for sub-national entity fiscal allocation liberalism.

Data did not support our findings for hypothesis (H4a) in which we had projected autonomy mediation in the relationship between inter-governmental transfers and budget performance. This falls short of the logic expounded by the fiscal federalism theory (Alesina & Perotti, 1996; Auclair, 2002; Ndegwa, 2002). Its theoretical thought posits that leverage in sub-national participation in grant allocation and application enhances grassroot budgetary efficiency. In practice, when local governments operate under restricted budget discretion, there is a tendency to suffer fiscal imbalances (both vertical and horizontal) and a possible loss of budget ownership confidence. Several fiscal federalism research work in Africa (e.g. Awio & Northcott, 2001; Braun & Grote, 2000; Conforti et al., 1998; Degefa, 2003; Larbi, 1999; Ndegwa, 2002) associate sub-national budget performance dysfunction to limited autonomy and participation.

We find mediation effects and data support in the relationship between budgetary institutionalization and budget performance (H4b) and audit and external scrutiny and budget performance (H4c). Studies (e.g. J’onsson, 1982; Kundishora, 2004; Kyobe & Dillinger, 2005; World Bank, 2004) report budget efficiency in LGs whose operations are autonomous in real terms to conform with budgetary guidelines, regulation, and supervision (institutionalization). Degefa (2003), McGill (2001) and Ndegwa (2002) attach budget credibility in Ethopian, Tanzanian and Kenyan-based local governments to strong institutionalization and effective audits. The secret is that autonomy and discretion in such entities is not cosmetic and playwrights of the governing politics but real and substantive (McGill, 2001; Ndegwa, 2002). In Uganda, a case in point is when LGs had limited say in the recent scrapping of the graduated poll tax (GPT) and subsequently required to abide by regulation governing its substitute revenue source (Moon & Williamson, 2010; Ministry of Local Government, 2012). GPT was an important local revenue source for LG activities and a core factor in their budget performance equation (Livingstone & Charlton, 2001; Uganda Debt Network, 2006). Our findings are therefore not only in tandem with the conventional empirical knowledge pool but also consistent with the core notion in the new public management (NPM) paradigm. NPM claims that no public entity can register operational and planning efficiency similar to those in the market place (corporate world) when it violates legislative directives and associated checks and balances (audits) (Larbi, 1999; Oates, 1999; Osborne & Gaebler, 1992).

Our last hypothesis (H4d) was that entity autonomy mediates the relationship between central government patronage and budget performance. Surprisingly, this proposition failed to secure support from the available data. We find this instance a unique case of pure mediation which according to MacKinnon et al. (2007) indicates mediation confounded by some antecedent factors. If the traditional logic in Baron and Kenny (1986) had been adopted, we would report no mediation. Degefa (2003), McGill (2001) and Ndegwa (2002) associate pure mediation disguising factors to be of social, economic and political nature. A possible explanation of LG autonomy under pure mediation is partisan political influence decried by district administrators and budget desk officials in Uganda (qualitative data).

Industrial psychology research (e.g. Slattery, Selvarajan & Anderson, 2008) claims demographic characteristics have a significant influence on mediation effects in behavioral and social science studies. In this research, we controlled for all biographical data. However, we partially associate our pure mediation findings to such factors based on evidence in those behavioral studies. In sum, the level of mediation obtained in the study suggests that, if local governments have real autonomy in financial planning and budgetary preparation and implementation, their budgets may attain expected performance standards (cf Abedian et al., 1996; Dafflon, 2000; Williamson et al., 2005).

Theoretical contributions

With this study, we make a number of contributions to public policy and budgeting theory in general and local government (LG) budgetary theory in particular. In the first instance, we extend research that has examined the influence of central government patronage on LG budget performance but has paid relatively little attention to the mediation effect of entity autonomy (e.g. Brosio, 2000; Cremer, Estache & Seabright, 1996; Livingstone & Charlton, 2001). This study contributes to this stream of research by explicating how LGs can adopt tailor-made innovations and strategies to create budget performance competencies capable of aligning them with central government expectations. The logic is that since central government policy-makers draw most of their patronage input from theoretical underpinnings (cf Larbi, 1999; Shah, 2003; Schacter, 2005; Wibbels, 2000), we provide insight and direction for LG authorities to this end.

Secondly, our research focuses on operations of specific local government units in a developing country Uganda.

This enabled us to engender novel theoretical arguments with the potential of enriching extant empirical fund for countries ambitiously embracing decentralization governance and particularly fiscal federalism.

Thirdly, paradigms and theories (e.g. NPM, fiscal illusion theory, fiscal federalism theory) that dominate the fiscal federalism debate were developed, tested and practiced in the developed western world. Configuring budgetary activities to attain required performance credibility within strict time limits by inexperienced LGs in poor countries can be a big challenge.

This is especially so if the entity has limited theoretical understanding (Lister & Betley, 1999; Shah, 2003). Accordingly, several African fiscal federalism scholars (e.g. Degefa, Gabor Soos, 2001; Kukkiriza, 2007; Kyobe & Dillinger, 2005) advocate for studies that can augment theory-practice realism in sub-national budgetary and resource allocation in our local settings. This research contributes to the theoretical fabric by generating bonds between budgetary practice and theory in resource constrained settings and, in so doing, questioning how such theories maintain their authenticity.

In a nutshell, our findings reveal the close connectivity between LG budgetary practice, theoretical underpinnings and policy. Consistent with extant literature, notably Gabor Soos, 2001, Livingston & Charlton, 2001, Wibbels, 2000 and Winer, 1980, some findings were in tandem with assumptions of key theoretical strands like revenue exaction theory, fiscal federalism theory, while others were in conflict.

As Aiken and West (1991) and Bagozzi and Phillips (1982) observe, policy is derived from theory and practice is at the core of practice. For instance, market-like value-for-money independent audits suggested in the new public management model (Aucoin, 1990; Larbi, 1999) was found negatively correlated with budget performance. The idea is that, if such audits are carried out in corrupt and autonomy-constrained LGs, they instead engender negative budget performance outcome (Auclair, 2002; Kukkiriza, 2007; Tanzi, V. 1995).

Empirical contributions

We have combined quantitative and qualitative methods to examine two important issues relating to budget performance in local government (LG): central government patronage (CGP) and the mediating role played by entity autonomy. Our results illuminate the direct effect on budget performance of the predictor CGP when acting both as an individual factor and when its constructs act interactively. This means that local governments and the central government must appreciate that the two are all pertinent ingredients to sustainable budget performance.

These pilot findings not only add to a holistic understanding of the entire central government patronage structure on local government activities but also highlights the otherwise ignored mediation role played by entity autonomy. Prior research has seldom paid attention to the LG autonomy factor. Some studies (e.g. Awio & Northcott, 2001; Brosio, 2000; Dafflon, 2000; Mugerwa et al., 2007) simply end at describing existing fiscal decentralization systems as “tilted and skewed”. The study strongly points out the crucial role autonomy can play and tries to bridge the gap in the literature that it is not only influential but is confounded by socio-political factors such as partisan politics which must be addressed. The results echo qualitative data position (opinions expressed by majority district administrators, budget desks, ministry and donor agency officials) that LG autonomy is cosmetic. Central government policy, not only in Uganda but elsewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa (Degefa, 2003; Keller, 2002; McGill, 2001; Ndegwa, 2002), tends to be autocratic when it comes to grant allocation and institutionalization to LGs. This study is of paramount importance for ambitious decentralization policies whose dream is to continuously create new LGs.

Fiscal federalism studies (e.g. Bretschneider et al., 1989; DFID, 2006; MacReynold & Fuhrer, 2002; Shah, 2003) globally caution the resultant negating effect large numbers of autonomy-deprived LGs have on resource allocation, resource basket, manpower capacity and associated service delivery standards.

Practical implications

Public sector budgeting in general and that of local government in particular is a function of a series of stakeholders. Sub-Saharan Africa fiscal federalism prior research (e.g. Bohn & Inman, 1996; Dafflon, 2000; Hoffmann & Gibson, 2005) singles out central government, development partners, local governments, civic leadership and the community as the main ones.

Results from this study impact local government (LG) policy at the central government level. Specifically, they highlight the need to balance grant management, employ realistic institutional mechanisms and conduct professional and objective audits in LGs.

International financial agencies (e.g. World Bank, International Monetary Fund), key partners in fiscal decentralization programmes in the developing world, also recommend participative budgeting and collaboration to realize LG budget efficiency (DFID, 2006; Shah, 2003; World Bank, 2004).

As partners and resource allocation agents for central government and donor agencies, LGs are expected to ensure that constitutional obligation is executed effectively. Our study explains the role LGs must play in this shared responsibility. Prior research (e.g. Islam, 2009; Treisman, 2000; Ndegwa, 2002) underscores the need for LG cooperation in the budgetary efforts to achieve budget performance. The results in this research echo the commitment and calls on LG authorities to realize the delicate mandate before them as grassroot people-representative units.

Finally, the study makes a unique practical contribution by highlighting the LG autonomy black box. Central and local government policy-makers must realize that in order to attain sustainable budgetary efficiency, LG autonomy must be accorded adequate attention. Conventional literature (e.g. Awio & Charlton, 2001; Degefa, 2003; McGill, 2001) argues that LG autonomy exists simply in name but is devoid of practical actuality. Another stream of research (e.g. Lister & Betley, 1999; McCleary, 1991; Shleifer, 1998) claims that LGs, especially those in corruption-ridden economies of Africa, abuse autonomy opportunities and thus full discretion should be restricted. The practical implication bottom line in the eyes of this study is then that of a working balance between central government and LGs on autonomy. This may take the form of monitoring and situational-based regulation (Garson, 2007; Von Hagen & Eichengreen, 1996).

Strengths, limitations and future research direction

A number of distinct empirical strengths and limitations are associated with this study. Firstly, unlike previous Sub-Saharan Africa local government research (e.g. Brosio, 2000; Kundishora, 2004; Keller, 2002), we employed independent LG administrator and employee ratings to maximize data collection opportunities.

This methodological innovation was apt for the dynamic Ugandan decentralization environment (the global LG structure proxy), in which various LGs are created ambitiously, regardless of operational experience, and thus compromising budgetary performance.

The limitations in this study were, however, quite many. For instance, we are only able to capture a snapshot of ongoing budgetary processes in local governments. It was not possible to involve all the measures that could adequately explain budget performance in these entities. Generalization based on that snapshot inquiry may therefore be of very limited application.

Second, we tried to define the study constructs as precisely as possible by drawing on the extant literature and theory. The definitions were accordingly validated by the practitioners, namely the district administrators, budget desk officials, employees involved in budgetary activities and ministry and donor officials. However, we cannot guarantee that such definitions are absolutely realistic proxies of the latent phenomena which are not fully measurable.

Third, all the scales used in the study exhibited acceptable psychometric properties, but, since self-assessment measures were employed, the threat of common methods bias (CMB) could not be ruled out completely. CMB has a tendency of sneaking in and silently inflating observed relations between variables. This threat was, however, mitigated by attempting to collect data from various sources (Podsakoff et at., 2003).

Finally, we controlled for demographic characteristics (gender, age, education etc). By so doing, we may have confounded some findings that could otherwise have arise. Additionally, the correlational evidence found does not necessarily reflect the causality proposed. It is plausible that predictors with innately stronger potential in influencing budget performance cannot be explicitly singled out.

As a point of future research direction, drawn on the basis of this doctoral pilot study, it is recommended that a bigger LG entity size be utilized to facilitate broader generalization. Full scale research envisions this reality with a view of addressing the foregoing limitations.

Conclusion

Budget performance still remains an elusive yet contentious goal in most local governments (LGs) across Sub-Saharan Africa. In Uganda, for instance, not much has changed notwithstanding its acclaimed two decade-old decentralization policy. Preliminary findings have shown that central government patronage (CGP) has an influential bearing on budget performance in these entities. This reality subsists if this factor (CGP) acts as stand-alone, but it exerts even more impactful force on budget performance when its constructs act interactively.

Most LGs lack the required autonomy and flexibility necessary to execute their resource allocation mandate effectively. The autonomy powers granted by central government are largely cosmetic but in practice confounded by factors apparently of socio-political setting. Limited autonomy tremendously undermines attainment of budget performance and confounds the individual effects that would arise from the predictor factors underlying constructs.

When central government patronage constructs, namely inter-governmental transfers, institutionalization, and audit and external scrutiny, are properly managed, it is very likely that budget performance can be realized to satisfactory levels and its eroded credibility restored. Nevertheless, the LG remains possibly the most effective institution at the grassroot level in resource allocation, if all the operational parameters can be efficiently managed.

References

1. Aiken, L.S. & West, S.G. 1991. Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA. Sage.

2. Alesina, A. & Perotti, R. 1996. Fiscal discipline and the budget process. American Economic Review. 86: 401-407.

3. Anderson, J.C. & Gerbing, D.W. 1988. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 186-192.

4. Armstrong, J.S. & Overton, T.S. 1977. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396-402.

5. Auclair, C. 2002. Federalism: Its principles, flexibility and limitations. A paper presented at 2nd International conference on decentralization, Manila, Philippines, July 25, 2002.

6. Aucoin, P. 1990. Administrative reform in public management paradigms, principles, paradoxes and pendulums (The 4 Ps). Governance. 115-137.

7. Awio, G., & Northcott, D. 2001. Decentralization and budgeting: The Uganda health sector experience. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 14: 75-88.

8. Bagozzi, R.P. & Phillips, L.W. 1982. Representing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27, 459-489.

9. Baron, R.M. & Kenny, D.A. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 51:1173-1182.

10. Belsley, D.A., Kuh, E. & Welsch, R.E. 1980. Regression Diagnostics: Identifying influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. New York. John Wiley and Sons.

11. Bohn, H. & Inman, R. 1996. Balanced budget rules and public deficits: Evidence from the US States. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy. 45: 13-76.

12. Bohrnstedt, G.W. 1983. Handbook of Research Academics. New York, Sage.

13. Borck, R. & Owings, S. 2003. The political economy of inter-governmental grants. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 33: 139-156.

14. Botner, S.B. 1985. The use of budgeting and management tools by state governments. Public Administration Review. 45: 616-620.

15. Braun, J.V. & Grote, U. 2000. Does decentralization serve the poor? IMF Conference on fiscal decentralization, 20-21, November, Washington DC.

16. Bretschneider, S.I., Gorr, W.L., Grizzle, G. & Klay, E. 1989. Political and organizational influences on the accuracy of forecasting state government revenues. International Journal of Forecasting. 5: 307-319.

17. Brignall, S. & Modell, S. 2000. An institutional perspective on performance measurement and management in the “new public sector”. Management Accounting Research. 11: 281-306.

18. Brosio, G. 2000. Decentralization in Africa. Paper presented at IMF/World Bank Fiscal Decentralization Conference, November 20-21, Washington DC.

19. Bryk, A.S. & Raundenbush, S.W. 1992. Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park. CA. Sage.

20. Buchanan, J.M. & Musgrave, R.A. 1999. Public finance and public choice: Two contrasting visions of the state. Cambridge. Mass. MIT.

21. Caiden, N. 1996. From here to there and beyond: Concepts and applications of public budgeting in developing countries. In. Caiden, N. (ed.), Public Budgeting and Financial Administration in Developing Countries. Greenwich, Conn. JAI Press. 3-17.

22. Campbell, D.T. 1955. The informant in quantitative research. American Journal of Sociology, 60, 339-342.

23. Carmines, E.G. & McIver, S.P. 1981.Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures in social measurement and current issues, eds. Bohrnsted, G.W & Borgatta, E.F., Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 65-115.

24. Castro, S.L. 2002. Data analytic methods for the analysis of multi-level questions: A comparison of inter-class correlation coefficients, Rwg(j), hierarchical linear modeling, within-and-between analysis, and random group re-sampling. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 69-93.

25. Conforti, P., de Muro, P. & Salvatici, L. 1998. An overview of decentralization in Sub-Saharan Africa. A paper prepared for the workshop on Decentralization and participation for sustainable rural economic development in Africa. Economic Development Institute. World Bank.

26. Cortina, J.M. 1993. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98-104.

27. Cremer, J., Estache, A. & Seabright, P. 1996. Decentralizing public services: What can we learn from the theory of the firm? Revue d’Economie Politique. 106: 37-60.

28. Dafflon, B. 2000. Fiscal Decentralization. Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation (SDC).

29. Degefa, D. 2003. Fiscal decentralization in Africa: A review of Ethopia’s experience. Economic Commission for Africa.

30. Denhardt, R.B. & Denhardt, J.V. 1999. Leadership for Change: Case studies in American Local Governments. Arlington, VA. Price Waterhouse Coopers Endowment for the business in government.

31. Department of International Development (DFID). (2006). Local government decision-making: Citizen participation and local accountability – Example of good and bad practice in Uganda. Building Municipality Accountability Series, International Development Department, University of Birmingham, UK, England.

32. Eisenhardt, K.M. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14, 488-511.

33. Eshatu Chole .1994. Issues of vertical imbalance in Ethopia’s emerging system of fiscal decentralization. Ethopian Journal of Economics. Vol.III. 2

34. Feng, Yi. 2005. Democracy, governance, and economic performance: Theory and evidence. Cambridge. MA. MIT Press.

35. Ferejohn, J. & Krehbiel, K. 1987. The budget process and the size of the budget. American Journal of Political Science. 31: 296-320.

36. Field, A. 2006. Discovering statistics using SPSS for windows. London. Sage.

37. Fjeldstad Odd-Heldge. 2001. Inter-governmental fiscal relations in developing countries: A review of issues. CMI Working Paper # II. Chr. Michelson Institute, Bergen, Norway.

38. Floyd, F. 1995. Improving survey questions, design and evaluation. A Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage.

39. Fountain Publishers. 2012. Uganda District Handbook-2012.

40. Gabor Soos. 2001. Dimensions of local government performance. Paper presented at the Workshop on Local autonomy and Local Democracy: Exploring the Link. Grenoble, April, 6-11.

41. Garson, D. 2007. Governance theory. Policy and Politics, 35: 1-5.

42. Gershberg, A. 1998. Decentralization, recentralization and performance accountability: Building an operationally useful framework for analysis. Development Policy Review.16: 405-431.

43. Government of Uganda.1997. Local Government Act. Printing and Publishing Corporation.

44. Gulu District Local Government.2009. Annual Budget Estimates, 2009-2010 Financial Year.

45. Guerrero & Herrbach.2009. Manager organizational commitment: A question of support or image. International Journal of Human Resource Management.20.7.1536-1553.

46. Guthrie, Flood, Liu & MacCurtain. 2009. High performance work systems in Ireland: Human resource and organizational outcomes. International Journal of Human Resource Management.20.1.112-125.

47. Hair, J.F.J., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L. & Black, W.C. 1998. Multivariate Data Analysis; 5th ed., Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Prentice Hall.

48. Hammond, T.H. & Knott, J.H. 1999. Political institutions, public management, and policy choice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 9: 33-85.

49. Hoffmann, D.A. & Garvin, M.B. 1998. Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Theoretical and methodological implications for organizational science. Journal of Management, 24, 623-641.

50. Hoffman, D.B. & Gibson, C.C. 2005. Fiscal governance and public services: Evidence from Tanzania and Zambia. University of California Press, San Diego. USA.

51. Hood, C. 1995. The new public management (NPM) in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. London School of Economics and Political Science. Accounting, Organizations and Society. 20: 93-109.

52. Hudson, A. & GOVNET. 2009. Background paper for launch of the work stream of Aid and Domestic Accountability. OECD-DAC GOVNET. Paris, OECD.

53. Hsueh-Liang, Wei-Chieh & Cheng-Yu. 2008. Employee ownership motivation and individual risk-taking behavior: A cross-level analysis of Taiwan’s privatized enterprises. International Journal of Human Resource Management.19.2311-2331.

54. Islam, S.M.A. 2009. Government expenditure and theory of efficient private and public finance. J. Bangladesh Agril.University. 7: 367-371.

55. Jaccard, J., Choi, K. W. & Turrisi, R. 1990. The detection and interpretation of interaction effects between continuous variables in multiple regression. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 467-478.

56. James, R.L., Muliak, S.A. & Brett, J.M. 1982. Causal Analysis Assumptions, Models and Data. Beverly Hills. CA. Sage.

57. J’onsson, S. 1982. Budgetary behavior in local government: A case study over three years. Accounting Organizations and Society. 7:287-304.

58. Jose, E.P. 2008. Welcome to the moderation/mediation help centre. School of Psychology, Victoria University of Wellington. Version 12.

59. Keller, E.J. 2002. Ethnic federalism, fiscal reform, development, and democracy in Ethiopia. African Journal of Political Science, 1.

60. Kenny, D.A., Kashy, D.A & Bolger, N. 1998. Data Analysis in Social Psychology in: The Handbook of Social Psychology, eds. Gilbert, D., Fiske, S. & Lindzey, J. McGraw Hill.

61. Kisembo, S.W. 2006. Hand book on decentralization in Uganda. Kampala. Fountain Publishers.

62. Kloot, L. & Martin, J., 1999. Strategic performance management: A balanced approach to performance management issues in local government. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association, Bordeaux, May 5-7

63. Kozlowski, S.W.J. & Klein, K.J. 2000. A multi-level approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual , temporal, and emergent processes, in: multi-level approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual , temporal, and emergent processes, eds. Kozlowski, S.W.J. & Klein, K.J. San Francisco, CA. Jossy-Bass, 3-90.

64. Kukkiriza, C. 2007. The process of decentralized planning and budgeting in local governments (cited in Decentralization and Transformation of Governance in Uganda). Kampala. Fountain Publishers.

65. Kumar, N., Stern, L.W. & Anderson, J.C. 1993. Conducting inter-organizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1633-1651.

66. Kundishora, P. 2004. Capacity building needs to support civic participation in sub-national budgeting in Uganda. Washington, DC. World Bank Institute.

67. Kyobe, A., & Dillinger, S. 2005. Revenue forecasting: How is it done? Results from a survey of low income countries. Working Paper 05/24. Washington, DC. Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund.

68. Larbi, G. 1999. The new public management approach and crisis states. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). UNRISD Discussion Paper # 112.

69. Lister, S. & Betley, M. 1999. Approaches to decentralization in developing countries. Sector Studies Series. Washington DC. World Bank.

70. Litvack, J., Junaid, M. & Bird, R. 1998. Rethinking decentralization in developing countries. Sector Studies Series, Washington DC. The World Bank.

71. Livingstone, I., & Charlton, R. 2001. Financing decentralized development in a low income country: Raising revenue for local governments in Uganda. Development and Change. 32: 77-100.

72. Lynn, L.E., Heinrich, C.J. & Hill, C.J. 2000. Studying government and public management: Challenges and prospects. Journal of Public Administration and Research Theory. 10: 233-262.

73. MacKinnon, D.P., Fairchild, A.J. & Fritz, M. 2007. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593-614.

74. MacReynold, M. & Fuhrer, K.2002. What to balance your budget? Constraint budgeting works. Public Management. 84: 19-21.

75. McCleary, W. 1991. The earmarking of government revenue: A review of some World Bank experiences. World Bank Research Observer. 6: 81-104.

76. McGill, R. 2001. Performance budgeting. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 14: 376-390.

77. Miller, D.C. 1983. Handbook of research design and social measurement. New York. Longman.

78. Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFPED). 2012. Local Government and Fiscal Administration.

79. Ministry of Local Government (MoLG). 2012. The consolidated local government budget desk and sector budgeting manual. Entebbe. Kampala. MoLG

80. Moon, S. & Williamson, T. 2010. Greater aid transparency: Crucial for aid effectiveness. ODI Project Briefing. 35. London. ODI.

81. Mugerwa, C., Juuko, S. & Oling, V. 2007. Interim report of the Uganda Donor Division of Labour Exercise. London. ODI.

82. Nachmias, F.C., & Nachmias, D. 1996. Research methods in the social sciences. New York. St. Martin’s Press.

83. Ndegwa, S.N. 2002. Decentralization in Africa: A stocktaking survey. Africa Region Working Paper Series, #40. World Bank.

84. Nunnally, J.C. 1978. Psychometric Theory (2nd ed.). New York. McGraw Hill.

85. Oates, W. 1999. An essay of fiscal federalism. Journal of Economic Literature. 37:1120-1149.

86. . 2001. Fiscal decentralization and economic development: Some reflections. Paper presented at the program for honoring Ronald McKinnon, June 1, 2002.

87. Obwona, M., Steffensen, J., Trollegaard, S., Mwanga, Y., Luwangwa, F., Twodo, B., Ojoo, A., & Seguya, F. 2000. Fiscal decentralization and sub-national government finance in relation to infrastructure and service provision in Uganda. National Association of Local Authorities, Denmark and Economic Policy Research Centre, Uganda.

88. Oppenheim, A.N. 1992. Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. London. Pinter Publishers.

89. Osborne, J.W. & Costello, A.B. 2005. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 10, 1-9.

90. Osborne, D. & Gaebler, T. 1992. Reinventing Government. Reading, MA. Addison, Wesley.

91. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.L. & Podsakoff, N.P.2003. Common methods biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology.85.5.879-903.

92. Qyen, E. 1990. Comparative methodology: Theory and practice in international social research. Newbury Park. New York. Sage.

93. Rondelli, D. 1981. Government decentralization in comparative theory and practice in developing countries. International Review of Administrative Services, 47, 133-145.

94. Satorra, A. & Bentler, P.M. 1988. Scaling corrections for Chi-square statistics in Covariance Structure Analysis in: Proceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section. Alexandria VA. American Statistical Association, 308-313.

95. Schacter, M. 2005. A framework for evaluating institutions of accountability in fiscal management. Public Budgeting and Finance. 229-245.

96. Schachter, H.L. 1997. Reinventing Government or Reinventing Ourselves. Albany, NY. State University of New York Press.

97. Shah, A. 2003. Fiscal decentralization in developing and transitional economies: Progress, problems and the promise. A paper presented at the Forum for Intergovernmental relations and improved service delivery in Pakistan. World Bank, 27-29 June, 2003, Bhurban, Murre.

98. Shleifer, A.1998. State v.private ownership. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 12: 133-150.

99. Slattery, J.P., Selvarajan, T.T. & Anderson, J.E.2008. The influence of new employee development practices upon role stressors and work-related attitudes of temporary employees. International Journal of Human Resource Management.19.12.2268-2293

100. Smoke, P. 2001. Fiscal decentralization in developing countries: A review of current concepts and practice. UNRISD Program on democracy, governance and human rights. Program Paper # 2.

101. Swailes, S. 2002. Organizational commitment: A critique of constructs and measures. International Journal of Management Reviews, 22, 522-552.

102. Tanzi, V. 1995. Fiscal federalism and decentralization: A review of some efficiency and macroeconomic aspects. A Paper prepared for the World Bank’s Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics, May 1-2. Washington DC. World Bank.

103. Treisman, D. 2002. Defining and measuring decentralization: A global perspective. Department of Political Science, University of California, Los Angeles, USA.

104. Tresch, R.W. 2002. Public Finance: A normative theory. New York. Academic Press.

105. Uganda Debt Network. 2006. The implication of the fiscal decentralization strategy in Bushenyi and Tororo districts: Review report. Kampala. UDN.7

106. Von Hagen, J. & Eichengreen, B. 1996. Federalism, fiscal restraints and European Economic Union. American Economic Review.86:134-138.

107. Wanous, J.P. & Reichers, A.E. 1997. How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 247-252.

108. Wasswa-Katono. 2007. Planning and budgeting for decentralization (cited in Decentralization and Transformation of Governance in Uganda). Kampala. Fountain Publishers.

109. Wibbels, E. 2000. Federalism and the politics of macroeconomic policy and performance. American Journal of Political Science. 44:687-702.

110. Winer, S. 1980. Optical fiscal illusion and the size of government. Public Choice.35.607-622.

111. World Bank. 1992. Governance and development. Washington DC. World Bank.

112. World Bank. 2004. The Republic of Uganda: Country integrated fiduciary assessment report. Country Department of Uganda, Africa Region.

Appendix A

Table i: Budget performance factor loadings.

Table ii: Central government patronage.

Table iii: Entity autonomy factor loadings.

Cite this paper

APA

Onyango-Delewa, P. (2013). Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government. Open Science Repository Public Administration, Online(open-access), e70081957. doi:10.7392/openaccess.70081957

MLA

Onyango-Delewa, Paul. “Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government.” Open Science Repository Public Administration Online.open-access (2013): e70081957.

Chicago

Onyango-Delewa, Paul. “Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government.” Open Science Repository Public Administration Online, no. open-access (May 4, 2013): e70081957. http://www.open-science-repository.com/central-government-patronage-and-budget-performance-in-local-government.html.

Harvard

Onyango-Delewa, P., 2013. Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government. Open Science Repository Public Administration, Online(open-access), p.e70081957. Available at: http://www.open-science-repository.com/central-government-patronage-and-budget-performance-in-local-government.html.

Science

1. P. Onyango-Delewa, Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government, Open Science Repository Public Administration Online, e70081957 (2013).

Nature

1. Onyango-Delewa, P. Central Government Patronage and Budget Performance in Local Government. Open Science Repository Public Administration Online, e70081957 (2013).

doi

Research registered in the DOI resolution system as: 10.7392/openaccess.70081957.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.