Open Science Repository Biology

doi: 10.7392/openaccess.45011830

Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa

Jason A. Turner [1], Caroline A. Vasicek [2], Michael J. Somers [3]

[1] Global White Lion Protection Trust, South Africa, [2] Flora Fauna Man, Ecological Services, South Africa, [3] Centre for Wildlife Management, Centre for Invasion Biology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Funding: This research has been funded by the Global White Lion Protection Trust, a non-profit conservation trust [IT 8575/02; 048-299NPO; 930019129 BPO]. Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests. Correspondence should be addressed to: [email protected].

Abstract

Background: Coat colour variation has been recorded in several mammalian taxa, including large felid species. White lions are a rare colour variant of the African lion, Panthera leo, that only occurred in the wild in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve and southern Kruger National Park, South Africa. Although white cubs were born in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve in 2006, 2009, 2011, and 2014, and in southern Kruger National Park in 2014 and 2015, no adult animals had been seen since 1994. It has been suggested that white coat colour prevents free-roaming lions from hunting successfully and therefore surviving in the wild. This hypothesis was investigated under managed free-roaming conditions in two fenced areas since no adult white lions existed in the wild at the time. Two separate groups of white lions were rewilded and their hunting success evaluated. Prey density, availability of preferred prey and habitat type were similar to that of the white lions’ natural habitat of Timbavati Private Nature Reserve. Wild tawny lions were released into the study area and their hunting success recorded. All kill data were then compared to that of wild tawny lions in other small wildlife reserves in South Africa.

Results: There was no significant difference between the mean kill rate or mean consumption rate of the two white lion groups and: (i) the tawny lion group in the same study area, (ii) wild tawny lions at the Madjuma Lion Reserve (MLR), Karongwe Game Reserve (KGR), Welgevonden Game Reserve (WGR), Makalali Game Reserve (MGR) and the Associated Private Nature Reserves (APNR) in South Africa.

Conclusions: White lions are capable of hunting self-sufficiently under managed free-roaming conditions in a small fenced area, suggesting that white coat colour does not prevent free-roaming white lions from hunting successfully in their natural habitat. We suggest therefore that the hunting behaviour of white lions be studied under fully free-roaming conditions.

Keywords: white lion, colour variant, leucism, hunting success, Greater Kruger Park.

Citation: Turner, J. A., Vasicek, C. A., & Somers, M. J. (2015). Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa. Open Science Repository Biology, Online(open-access), e45011830. doi:10.7392/openaccess.45011830

Received: May 4, 2015

Published: May 8, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Turner, J. A., Vasicek, C. A., & Somers, M. J. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Contact: [email protected]

Background

Coat colour variation, resulting from gene mutations, is present in several mammalian taxa and has been detected in mammals as far back as 14000 ybp [1, 2]. Natural intraspecific coat colour variation has been observed in a number of mammalian species including deer mice (Peromyscus spp.), black bear (Ursus americanus), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), leopard (Panthera pardus), Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) and African lion (Panthera leo) [1, 5-7]. Natural selection determines which coat colour will persist based on whether the colour is a benefit or not to the survival of that species [3, 4]. Common colour mutations in big cats are albinism (pure white), chinchilla (white with pale markings), leucism (partial albinism/cream) and melanism (black) [1].

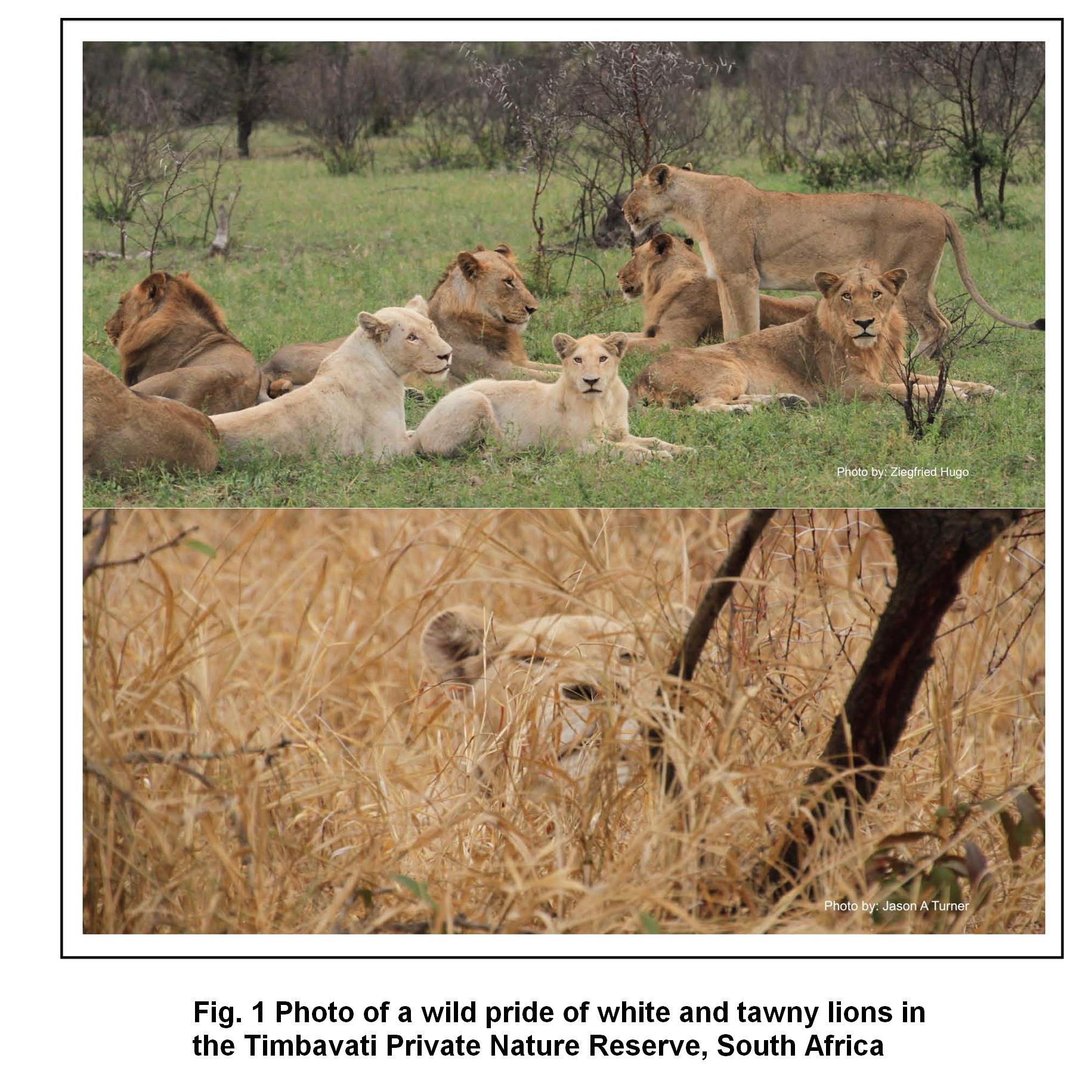

The white lion is a rare phenotype or colour variant of the African lion Panthera leo that has a white coat colour (Figure 1) with either yellow, blue or green eyes, and has only ever been recorded in the wild in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (TPNR) and southern Kruger National Park (KNP) - the Greater Timbavati Region - in South Africa [8-11].

The white coat colour is not due to albinism [10], but rather leucism resulting from a double recessive allele [12]. The presence of white lions was documented for the first time in the southern KNP in 1959 [10] and in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (TPNR) in 1975 [8]. The frequency of occurrence of white lions in their natural endemic habitat increased [10] until they were removed [11]. From the 1970s onwards, prized for their rarity, the white lions and many normal coloured (tawny) lions carrying the white lion gene were removed from the wild and put into captive breeding and trophy hunting programmes and sent to zoos and circuses around the globe [9,11]. In combination with lion culling in southern Kruger National Park [13] and trophy hunting of pride male lions in Timbavati Private Nature Reserve [14] it is our assertion that these actions removed all of the white lions and decreased the white lion gene pool, such that white lions were technically extinct from 1994 to 2006. At the time of writing (2015), a total of 17 births of white lions had been recorded over the past 8 years, in 5 different prides in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve, neighbouring Umbabat Private Nature Reserve and southern Kruger National Park, confirming that white lions are a natural occurrence and the recessive gene is still present in the wild population. However, no scientific study had been done on the white lions or their hunting behaviour, since the relevant conservation authorities perceived that white lions cannot hunt due to a lack of camouflage [9]. This perception has never been tested scientifically and is not based on any quantifiable data.

Here we investigate the hunting ability of white lions in their natural habitat using the following hypotheses and predictions:

- Hypothesis a: the hunting success of white lions in their natural habitat is similar to that of wild tawny lions, suggesting that white lions can survive in the wild.

- Hypothesis b: the hunting success of white lions in their natural habitat is lower than that of wild tawny lions, suggesting that white lions cannot survive in the wild.

For the present study, this translates into two predictions:

- Prediction a: white lions show similar hunting success to other wild lions.

- Prediction b: white lions show lower hunting success than other wild lions.

At the time of the present study there were no adult white lions in their natural distribution range. Two groups of captive born white lions were therefore rewilded by using a soft release [15] approach, and their hunting behaviour studied. Rewilding is the process by which captive bred animals are reintroduced into the wild. Due to high failure rates and high costs, rewilding is generally discouraged [16-19]. Additionally, there is a perception that certain captive felids, particularly lions, cannot survive in the wild [17]. However, the use of captive-born individuals becomes necessary where no wild representatives remain or when the surviving wild population is no longer viable [20]. Soft release is more successful than hard release [21] because it involves a period of captivity at the release site during which the animal can adjust to its surroundings [22, 23] and other possible animals or conspecifics that may be released with it [15, 24]. After the soft release of the white lion groups, their hunting behaviour was recorded and compared to that of (i) a pair of wild tawny lionesses that were observed in the same study area, and (ii) other scientifically documented wild and reintroduced lions in South Africa.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

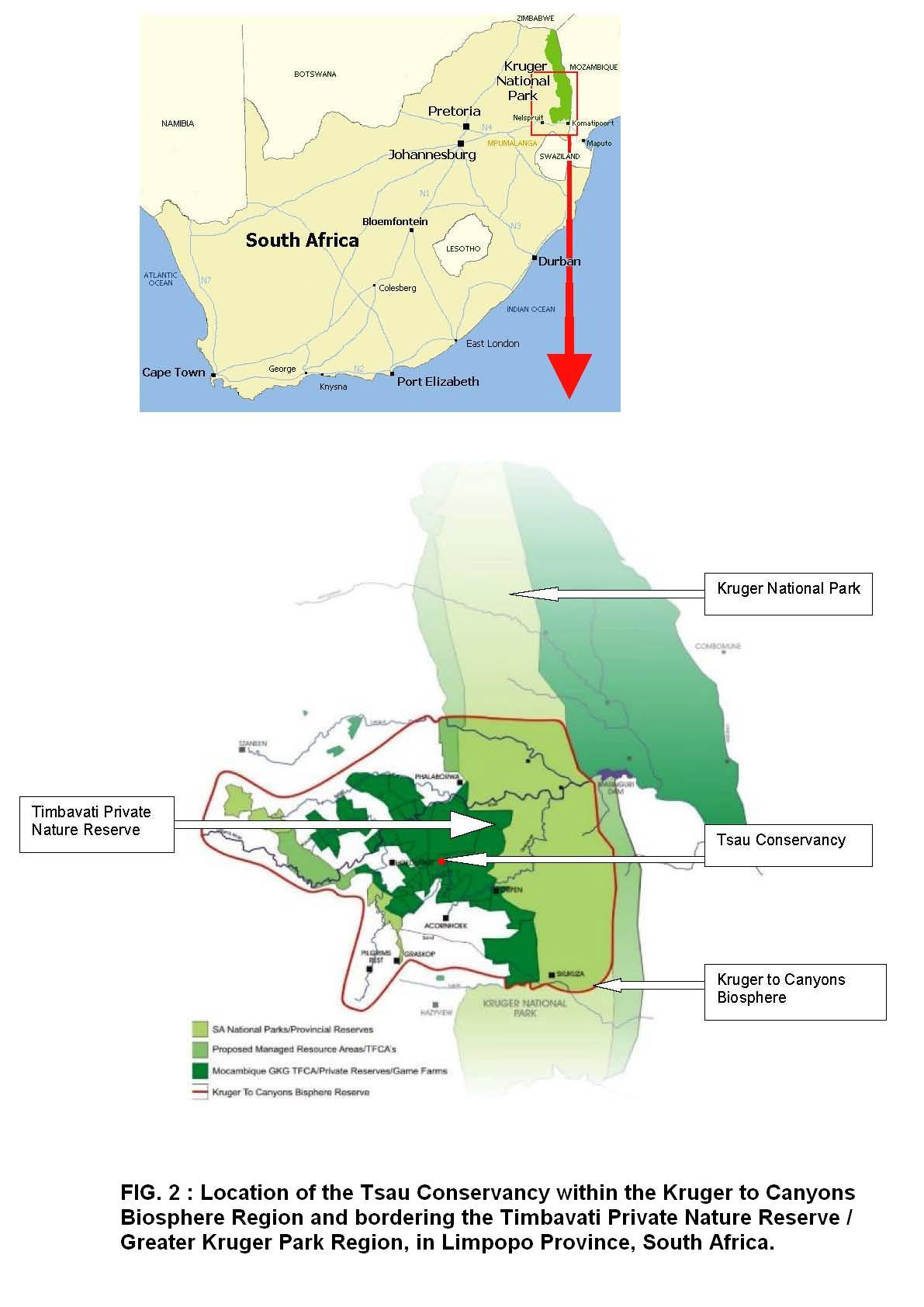

The rewilding took place in two rehabilitation areas within the Tsau Conservancy, a 2000 ha wildlife area. The size of the rehabilitation areas were 300 ha and 700 ha respectively. The Tsau Conservancy is located in the Lowveld of South Africa, bordering the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (TPNR), the natural distribution range of the white lions (Figure 2). The Tsau Conservancy consists of natural bushveld that is classified as Arid Lowveld [25]. It is an undulating landscape consisting of plains, woodlands of various densities and riverine vegetation. There are several permanent water points as well as numerous seasonal water points and streams in each of the rehabilitation areas. In accordance with the IUCN Guidelines for Reintroduction [26], the rehabilitation area was used to provide the lions with the opportunity to gain the skills needed to survive self-sufficiently. The rewilding took place under managed free-roaming conditions to enable the lions to roam freely whilst being protected from poachers, conspecifics and large dangerous prey species. The managed conditions also ensured the disease free status of both the lions and their prey.

The area is populated by indigenous flora and fauna and contains the following mammalian prey species: blue wildebeest, Connochaetes taurinus, common warthog, Phacochoerus africanus, Cape porcupine, Hystrix africaeaustralis, impala, Aepyceros melampus, steenbok, Raphicerus campestris, aardvark, Orycteropus afer, bushbuck, Tragelaphus scriptus and grey duiker, Sylvicapra grimmia. Conspecifics and large prey animals such as African buffalo, Syncerus caffer, and giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis, which are dangerous for inexperienced lions to hunt, were excluded from the rehabilitation area. Black-backed jackals, Canis mesomelas, and caracal, Caracal caracal, occur in the rehabilitation area, and both leopard, Panthera pardus, and spotted hyaena, Crocuta crocuta, have been seen, but are not considered resident in the area. Wild lions occur on neighbouring properties that border three of the four boundary fences of the rehabilitation area. The entire rehabilitation area is surrounded by an electrified (9000 V) double predator-proof fence that is 2.4 m high. The double fence minimised the risk of conflict with the lions from the three neighbouring private nature reserves and also reduced the risks of the lions escaping the area if a prey animal ran into the fence whilst being hunted by the lions.

An aerial game count was conducted prior to releasing the lions, to determine the prey density within the rehabilitation areas. Additional aerial game counts were conducted annually at the same time of year, to monitor prey population trends. The smaller rehabilitation area (300 ha) had a limited number of prey species due to its small size: blue wildebeest, warthog, impala, common duiker and steenbok. The larger rehabilitation area (700 ha) could sustain a wider variety of prey species: blue wildebeest, warthog, impala, waterbuck, bushbuck, Burchell’s zebra, Livingstone’s eland, nyala, greater kudu, common duiker, steenbok and porcupine. The prey populations were replenished on an annual basis typically in March or April to ensure the prey density was similar to that of the white lions’ natural habitat of the TPNR. The exception was in October 2006 when the blue wildebeest population in the 300 ha area was replenished. Prey density estimates for the TPNR were obtained from Turner (2005) [27]. The annual replenishment of prey is in accordance with other small reserves that have free-roaming lions, such as Madjuma Lion Reserve in the Limpopo Province of South Africa [28], which similarly replenish prey on an annual basis.

The size of the rehabilitation areas was optimal for the rewilding process and this preliminary study, but the long-term objective is to study wild white lions within the open system of the Greater Timbavati - Kruger Park Region.

Lion Particulars

Captive-born lions were utilised for the initial part of the study on white lions (August 2005 to March 2006) because there were no adult white lions in the wild at the time, and it was surmised that the white lion had become extinct in the wild in their natural endemic habitat. Moreover, it was uncertain whether the gene responsible for the white coat colour still existed in the wild. Although self-sufficient free-roaming white lions were also reported in two wildlife reserves in the Western Cape (Sanbona Wildlife Reserve) and Eastern Cape (Pumba Private Game Reserve) in South Africa, these reserves are not in the natural endemic range of the white lions and no scientific evidence was available on their hunting behaviour. The white lions used for this study comprised of two rewilded white lion groups and a wild introduced tawny lion group. Rewilding is the process by which captive bred animals are reintroduced into the wild when no wild representatives remain or when the surviving wild population is no longer viable. Using the soft release technique, the two white lion groups were released into separate (fenced) rewilding areas of natural bushveld within the greater endemic range of the white lion. The founder white lion group (White Lion Group A) consisted of a white lioness and her three white offspring (two males and one female) that were acquired from the Johannesburg Zoo when the cubs were 3 months old, to be rehabilitated and introduced to managed free-roaming conditions. The lioness had the highest genetic integrity of any white lion in existence at the time, originating from two different bloodlines, with the mother of the lioness being wild-born. Though the white lioness was hand-reared, her cubs were not. A stringent protocol with no human contact or activity on foot, and minimal human imprinting during monitoring was applied to rehabilitate the lions. A soft release approach was taken, whereby the founder group was held temporarily in a 1.5 ha acclimation boma (enclosure) before been released into the managed free-roaming conditions. This approach is in accordance with the principles outlined in the National Norms and Standards for the Sustainable Use of Large Predators in South Africa (section 9 (1) of the National Environmental Management Biodiversity Act 10 of 2004). The adult lioness was 6 years old and her three white offspring were 3 years old at the time of release into the rewilding area. The second white lion group, White Lion Group B, was studied 3 years later (June 2010 to February 2011), and consisted of the rewilded daughter of the founder lioness (6 years old), together with a captive-born adult white male (12 years old) and their three wild-born offspring (1.3 years old) which were released into the managed free-roaming conditions of a 700 ha rewilding area. The wild tawny lion group, Tsau Tawny Lion Group, was comprised of two adult lionesses (4 years old) that were released into the same 300 ha rewilding area as the founder white lion group, in August 2009, 3 years after the founder white lion group had been relocated to a new area at the Tsau Conservancy.

Monitoring

The adult lions were fitted with VHF radio tracking collars (148 to 152 MHZ), and two of the cubs were fitted with internal VHF tracking transponders (148 to 152 MHZ), prior to release. The lions were monitored daily, in the rewilding area from a closed vehicle to minimise conditioning. Radio telemetry was used to locate each of the lion groups, three times a day at sunset, midnight and sunrise. These were times that coincided with the lions’ peak activity periods. The lions were monitored for 1 to 5 hours, depending on how active the lions were during each monitoring session. Constant monitoring was deemed counter-productive to the rewilding process of the white lions, as the vehicle may have alerted potential prey and hindered the hunting success of the lions. Whenever possible, the lions were located visually during every monitoring session. The lions were approached up to a distance of 15 to 20 m, close enough to observe if a kill had taken place but distant enough not to disturb them. At each monitoring session the lions’ physical well-being was assessed and data on the date, time, location and activity of the lions were collected, as well as the species, age and sex of the prey killed and a subjective belly score [29]. If, due to distended stomachs and/or evidence of blood on the lions’ bodies, it was obvious that they had made a kill but no remains were found, then it was recorded as an unknown kill. Each of the lion groups were studied at a similar time of year, and for a similar duration to ensure that the data were as comparable as possible.

Data analysis

Data were collected for an 8 month observation period for each of the three lion groups studied. The observation period for the white lion groups was started once the white lions were hunting without human intervention. The white lion groups were considered to be self-sufficient once it was no longer necessary to supplement them with a carcass to sustain them, 2 months after release into the rewilding area. No correction factor was applied to the kill data to account for the smaller sized kills that may have been consumed entirely and therefore not recorded, since this is probably balanced out by the fact that aerial counts are biased towards larger sized animals [30]. Due to the non-invasive monitoring approach used, it can be assumed that smaller kills such as impala were missed and the number of kills recorded is therefore a minimum.

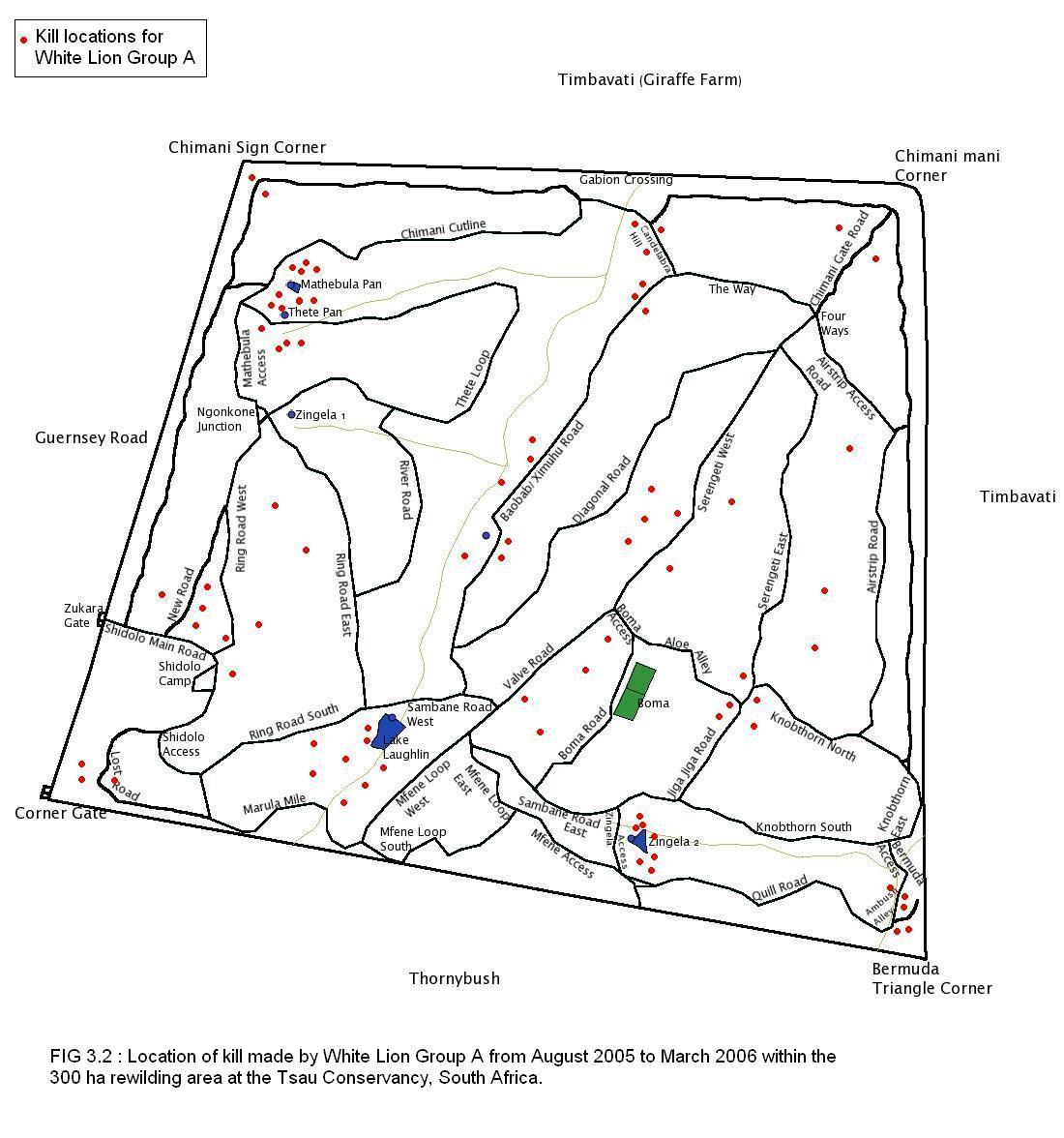

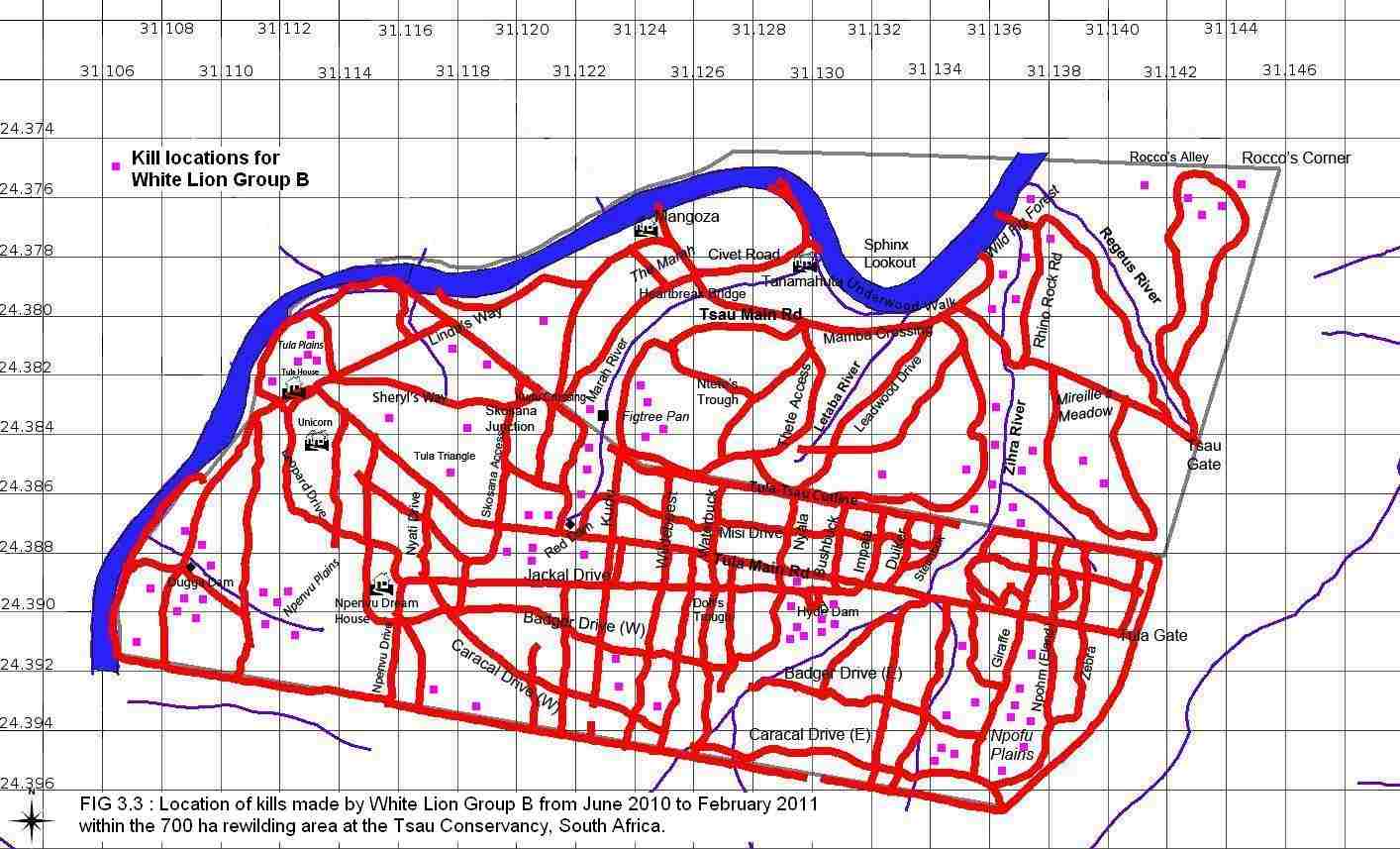

The GPS (Global Positioning System) location of kills were recorded and imported into an Arcview Global Information System package (Arcview 3.2) [31], from which a map was generated showing the kill locations within the study area and allowing a comparison between the three lion groups studied.

Although the age of prey animals was recorded in the kill data when possible, the present study only compared these data with that of the Tsau Tawny Lion Group, since the same observation technique was used and data were therefore comparable. Data were combined for White Lion Group A and B to make the data more robust. The Mann-Whitney Test was used to compare the age selection of the White Lion Groups with that of the Tsau Tawny Lion Group. There were too many unknowns to include a meaningful analysis of the sex selection by the lion groups. The live prey number of a species at any one time was calculated by deducting the recorded number of killed individuals and natural mortalities from that provided by the aerial game count.

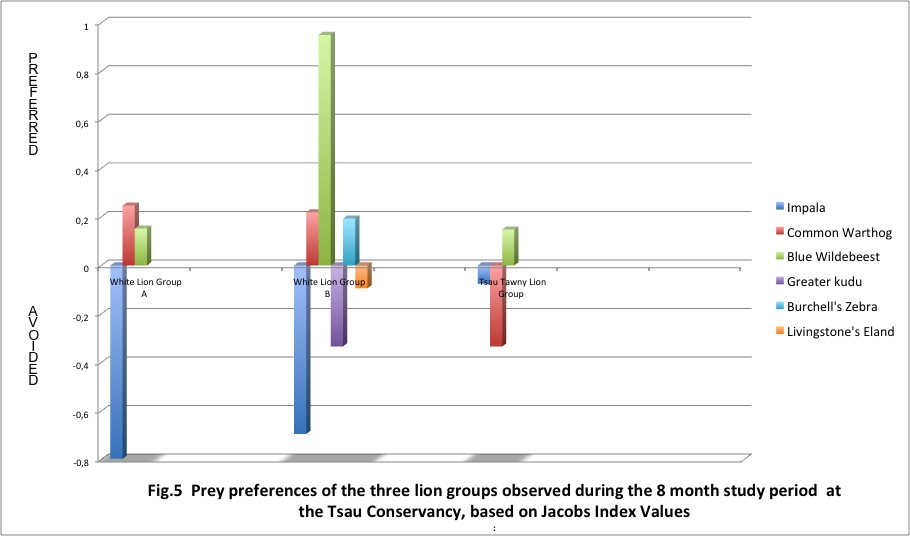

Overall dietary preferences were calculated by using the data from observed kills and applying Jacob’s Index (1974) [32], a modified version of Ivlev’s electivity index (D = r – p ÷ [r + p] – 2rp) in which r is the proportion of each type of prey killed by the founder lion pride and p is the proportion of each prey species available in the rewilding area. The standardized values for Jacob’s Index range from +1.0 to -1.0, where +1.0 indicates the maximum preference by the lions for a particular prey species (ie. a lion killing frequency greater than the relative abundance of the prey animal), whereas a Jacob’s Index of -1.0 indicates the maximum avoidance by the lion group for a particular prey species (ie. a lion killing frequency less than the relative abundance of the prey animal). The Jacob’s Index [32] was calculated for the most frequently killed prey species of the lion groups studied, for a period of 8 months of hunting self-sufficiently. However, the increase in blue wildebeest numbers (to achieve the correct prey density) 2 months after white lion group A had been hunting self-sufficiently, necessitated the calculation of the weighted mean of the Jacob’s Index of the first 2 months and the following six months. Utilising the kill data collected during the 8 month study period, the mean food consumption rate (kg/LFU /day) and kill rate (days / kill) were calculated for the two rewilded white lion groups and the Tsau Tawny Lion Group. In accordance with Van Orsdol (1982) [33] and Power (2002) [28] the food consumption rate was calculated per adult lioness or lion feeding unit (LFU), with the age and size of the lions in each pride being taken into account when determining the mean daily consumption rate. This classification assumes that adult males eat 1.5 times as much as females and are therefore 1.5 LFU, and large cubs (2–3 years) are 0.75 LFU, medium cubs (1–2 years) are 0.5 LFU, and small cubs are 0.25 LFU.

In order to determine if the kill rate and food consumption rate of the rewilded white lions was statistically different from that of wild tawny lion prides, data collected during the 8 month period were compared with data for: (i) Tsau Tawny Lion Group at the Tsau Conservancy, (ii) wild tawny lions in the neighbouring APNR [27], (iii) wild reintroduced lions in the Madjuma Lion Reserve (MLR), adjacent to Mabula Game Reserve (MGR) [28], (iv) wild reintroduced lions in the Welgevonden Private Game Reserve (WGR) [34], and (v) wild reintroduced lionesses (alone or in a pair with or without cubs) in the Karongwe Game Reserve (KGR) [35]. The MLR, WGR and KGR are all small fenced reserves that have lions, within the Limpopo Province, and the APNR is a large conservancy open to the Kruger National Park, within both the Limpopo and Mpumulanga Provinces of South Africa. The Kruskal – Wallis (KW) Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was utilised to compare the mean kill rate and mean food consumption rate of the two white lion groups with that of the corresponding rates for the wild tawny lions in the Tsau Conservancy, APNR, MLR, WGR, MGR and KGR, when available. A non-parametric statistical test was used since the distribution of the data did not conform to the assumptions of normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) [36]. Even when the data were transformed using the square root, reciprocal and log function, the data failed the normality test. The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

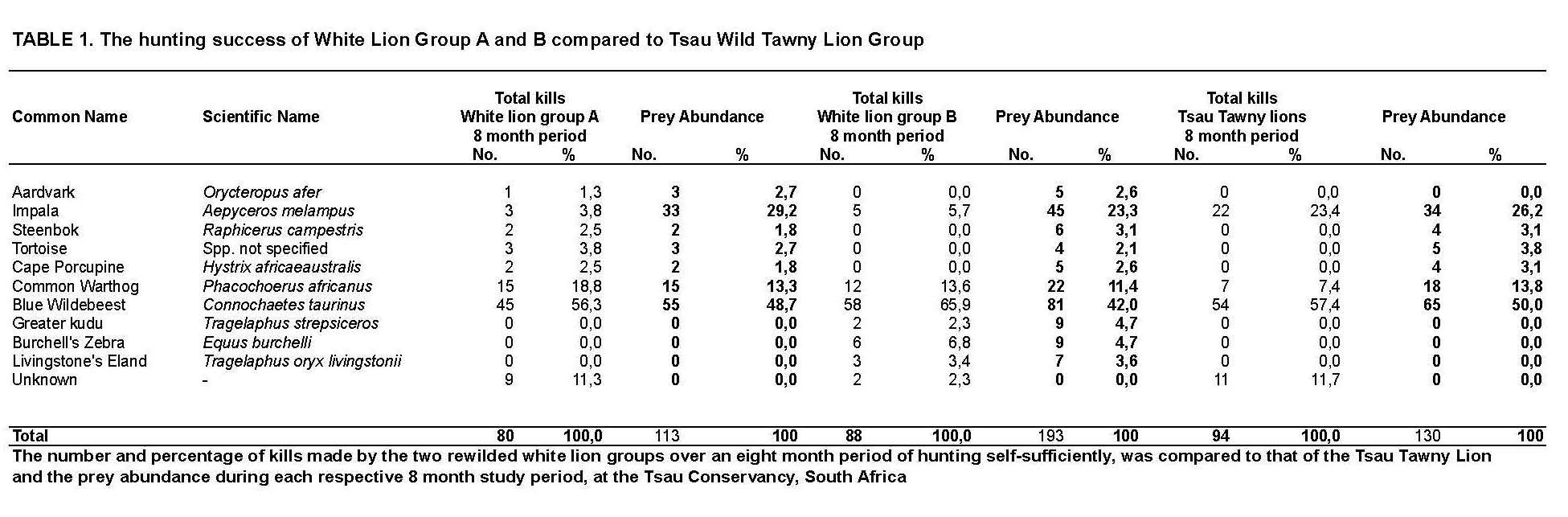

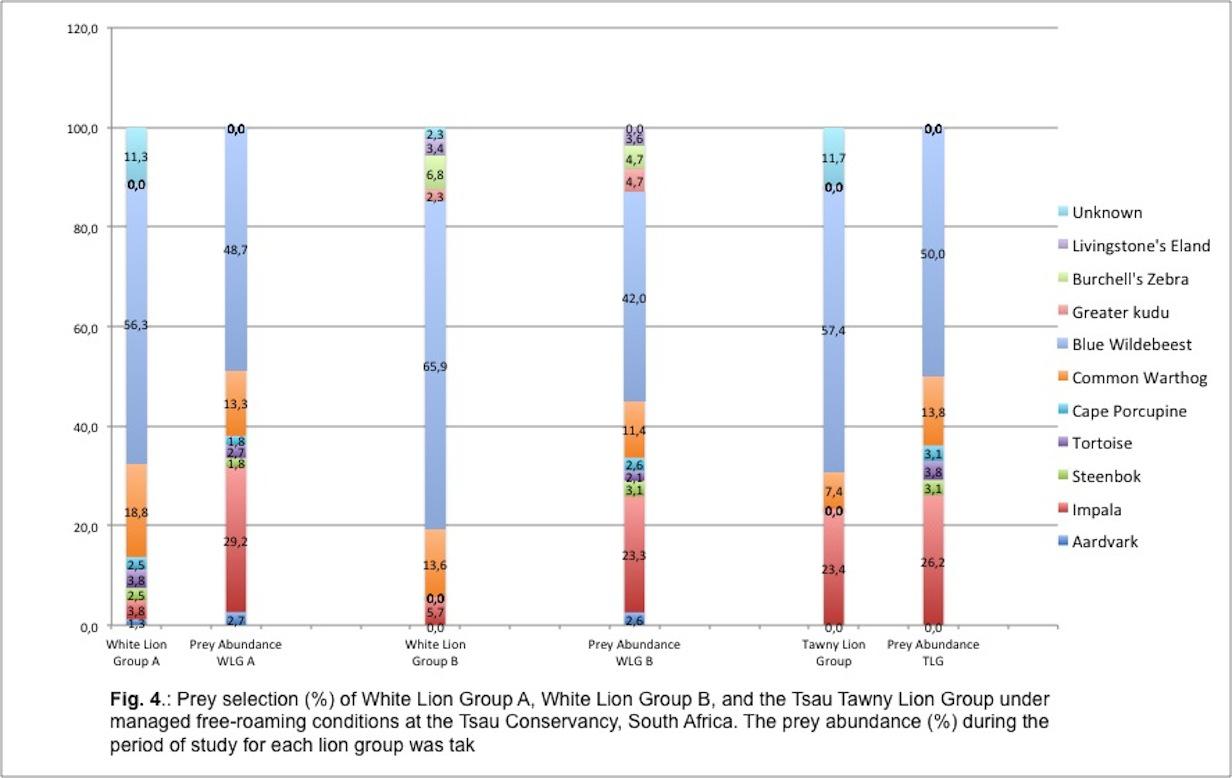

A total of 80 kills were recorded for White Lion Group A, 88 kills for White Lion Group B, and 94 kills for the Tsau Tawny Lion Group, during the 8 month period of observation on each lion group. Figures 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3 show the location of kills made by the three lion groups, indicating that the majority of kills were made close to waterpoints, drainage lines and open plains, and a relatively low number of kills were made at the boundary fence.

Table 1 and Figure 4 indicate the kill frequency by the three lion groups for the 10 prey species recorded during this study, compared to the prey abundance (%) for each lion group during the period of study.

Of the 10 prey species White Lion Group A selected seven types, White Lion Group B six types, and the Tsau Tawny Lion Group selected three types of prey. The two prey species that were killed by all three lion groups were the blue wildebeest and common warthog. The prey species selected at the highest frequency by the three lion groups was the blue wildebeest. Common warthog was the second most frequently killed prey species for the two white lion groups, and the third most frequently killed by the Tsau Tawny Lion Group. The impala was the second most frequently killed prey species by the Tsau Tawny Lion Group. By contrast, impala was the least frequently killed prey by the white lion groups. The Jacob’s Index values confirm that the white lion groups avoided hunting impala and indicate that the White Lion Group A showed a preference for warthog whilst the White Lion Group B preferred blue wildebeest. The Tsau Tawny Lion Group selected blue wildebeest and impala in accordance with their availability, but killed warthog less frequently than expected by their abundance. (Figure 5).

The White Lion Groups A and B selected 84% adults and 16% subadults, and similarly the Tsau Tawny Lion Group showed a greater selection for adults (80%) compared to subadult (20%) prey animals. There was no significant difference between the age selection of the White Lion Groups and the Tsau Tawny Lion Group (Mann-Whitney U = 10.000, df = 4, P = 0.675).

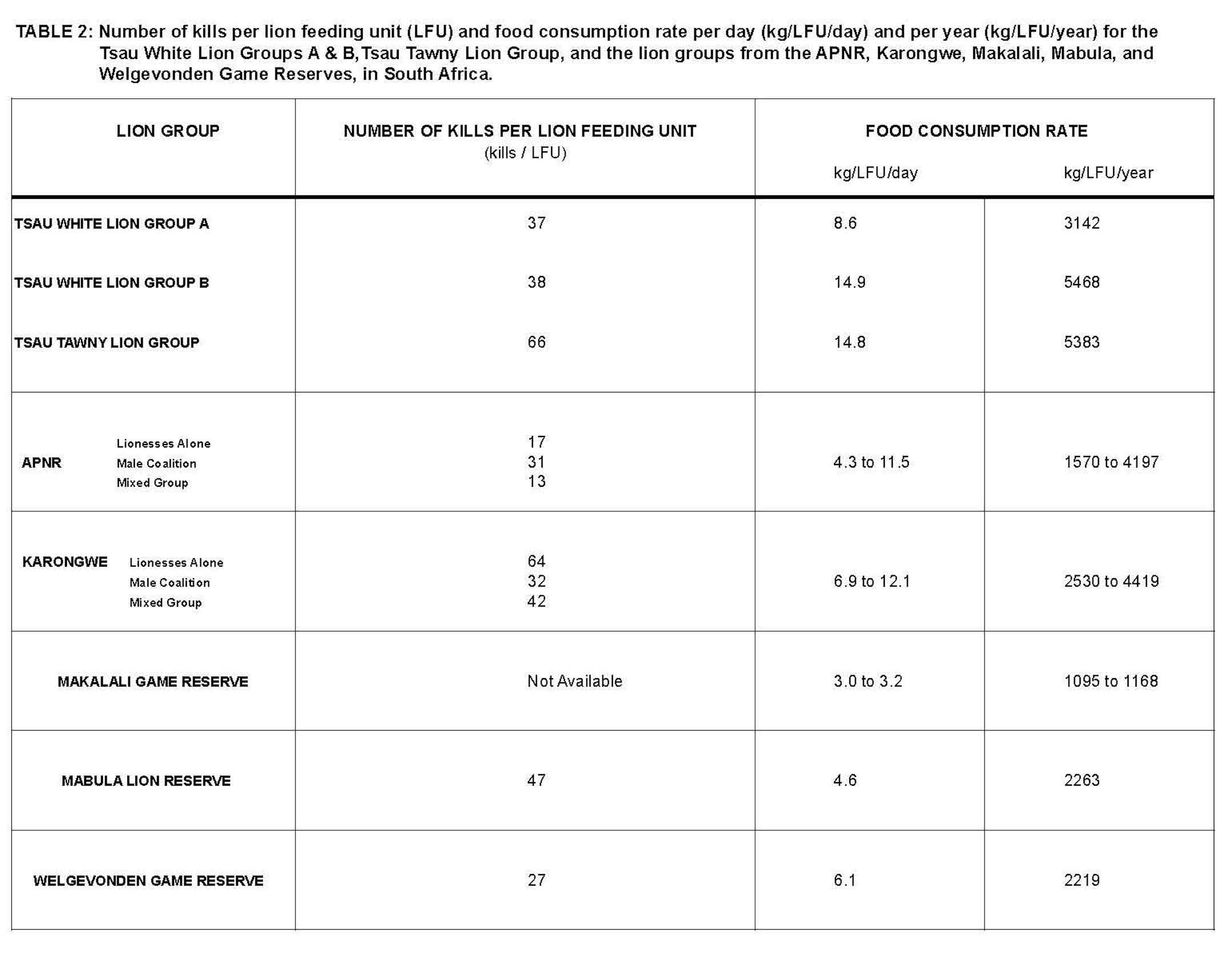

The mean kill rate for White Lion Group A (1 kill every 3.038 days) and White Lion Group B (1 kill every 2.731 days) during the 8 month period lies between that observed for the wild tawny lionesses at Karongwe and the wild tawny lions reintroduced to the Madjuma Lion Reserve (Figure 6). No significant differences (KW = 6.776, n = 9, P = 0.561) were found between the mean kill rate for the white lions and the kill rates of the wild tawny lionesses (1 kill every 2.550 days) at the Tsau Conservancy, the three wild tawny lion prides of the nearby APNR, the reintroduced wild tawny lion prides in the MLR and WGR and the reintroduced lionesses in KGR. Similarly, the mean kill rate of the two white lion groups displayed no statistical difference to that of the Tsau Tawny Lion Group (KW = 0.225, n = 9, P = 0.894).

The mean food consumption rate of the two white lion groups displayed no statistical difference to that of the Tsau Tawny Lion Group or the lion prides of the APNR, MLR, WGR, MGR and KGR (KW = 12.573, P = 0.083) (Table 2). The results of Dunn’s Multiple Comparison test [37] indicated that no significant difference exists between the food consumption rate of any of the lion groups compared.

Discussion

This study shows that if a strict rewilding protocol is followed with minimal human habituation, captive-born lions can be successfully introduced to managed free-roaming conditions. We also show that rewilded lions can be efficient hunters in the controlled conditions we provided. Despite our small sample size and the small size of the lion territories, our data indicate that the white lions studied were as efficient hunters as the normal tawny coloured lions observed in the same study area. Both historical and recent observations of wild white lions in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve (65 000 ha) support these findings [49, 50].

Prey species selection

Lions are highly adaptable in terms of their prey selection, hunting strategy, killing technique, activity pattern, and use of different habitat types. They eat any suitable food that is abundant and accessible, and their diet is more varied throughout their geographic range than that of any other large cat [38]. In the KGR lions have been recorded to select 21 different prey species [35], and in the KNP over 37 prey species [39]. The white lion group preyed on just seven prey species, but this number cannot be directly compared to that of the KGR and KNP, due to the controlled conditions of the rewilding area where the lions’ prey base was managed and the number of potential prey species purposely limited when compared to lions in fully free-roaming conditions. Additionally, the white lions’ situation was different in terms of group composition and founder members being captive-born. However, several studies have shown that generally less than five medium-sized to large ungulate species constitute 75% of the diet of lions [28, 40, 41, 42, 45].

Numerically, blue wildebeest were the white lions’ preferred prey (61% of total kills) followed by warthog (16% of total kills). This is consistent with findings for the Tawny Lion Group and the wild prides in the MLR and KGR [28, 35], but opposite to the observations in the Greater Makalali Conservancy, Limpopo Province, where the lions’ main prey was warthog, making up 30% of their diet, followed by wildebeest (18%) [42]. By contrast, warthog and wildebeest are not amongst the two most preferred lion prey in the APNR, although both warthog and wildebeest were hunted at a frequency greater than their relative abundance [27]. Two further studies also observed that lion tend to kill both wildebeest and warthog with greater frequency than their abundance [28, 40].

Although both the white lion groups and the Tsau Tawny Group showed a selection for blue wildebeest and warthog, these lion groups similarly showed no significant preference or avoidance for any of the available prey species. The latter is most probably due to the controlled (managed) circumstances of the study area. Consistent with the findings of numerous other lion studies in similar habitat types, impala were clearly not the most preferred prey of the white lion groups [27, 28, 34, 35, 39, 40]. The impala was the second most frequently killed prey species of the Tsau Tawny Lion Group probably because it was likewise the second most abundant prey species. Additionally, studies show that lionesses tend to select impala more frequently than male lions due to the evasive speed of the impala [40]. A similar reasoning is possible for the inexperienced white lion groups which were still perfecting their hunting technique and, therefore, selected easier prey. However, the more experienced and successful White Lion Group B still avoided selecting impala.

Prey age selection

The white lion groups selected larger prey as they honed their hunting technique, as did the Tsau Tawny Lion Group. This observation is also consistent with that observed for a pair of rewilded tawny lions released in the Luangwa Game Reserve in 1961 [46]. Despite being at a disadvantage in having to learn to hunt, the white lion groups preferred to hunt adult prey animals. This is consistent with the findings of other studies [27, 28, 35], though these studies point out that the methodology may have biased this finding toward large adult kills, as small kills, which are consumed rapidly, are more difficult to detect. Additionally, independent of their availability, medium to large prey species (190 to 550 kg) are preferred by lions [42]. With a mean weight of 215 kg, an adult female blue wildebeest in the KNP [45] fits into the lower limit of this range. This is consistent with our observation for White Lion Group B, for which several equally sized or larger prey species, such as greater kudu, waterbuck and eland, were available, yet this lion group selected blue wildebeest at the highest frequency. By contrast, the predilection of White Lion Group A and the Tsau Tawny Lion Group for adult blue wildebeest, as well as adults of any of the smaller prey, is better explained by the fact that the blue wildebeest was the largest and most abundant prey species available.

Hunting success

Within 2 months of being released into managed free-roaming conditions, both white lion groups attained hunting self-sufficiency, and within 3 months of being released, both groups displayed a kill rate that was consistently similar to that of lions in the APNR [27], MLR [28], WGR [34] and KGR [35]. This was the case despite the number of kills that may have been missed due to the non-invasive methodology applied in the present study, making the white lion kill rate an absolute minimum. By comparison, the five lion studies with which this study is being compared either monitored the lions continuously or used a correction factor to account for kills that may have been missed.

The mean daily food consumption rate of lions may vary considerably in both fenced ecosystems (KGR) [35], and open ecosystems (APNR) [27]. The study in KGR observed lion kill rates varying from one kill every 1.6 days to one kill every 16.4 days, depending on group composition and season [35]. As the kill rate of the white lion groups was similar to that of the Tsau Tawny Lion Group and the wild tawny prides in the aforementioned reserves, it is not surprising that the number of days between kills was also similar. The kill data show that both white lion groups hunted successfully with a kill rate and food consumption rate comparable to the Tsau Tawny Lion Group in the same study area. Although the number of kills made per LFU by the Tsau Tawny Lionesses was much higher than the White Lion Groups, the food consumption rate per LFU was comparable for White Lion Group B. Similar to the lionesses at KGR, the Tsau Tawny lionesses selected smaller prey (ie. impala) and a high percentage of juveniles, whilst the Tsau White Lion Groups selected larger prey (ie. blue wildebeest) and a greater percentage of adult prey. The lionesses therefore made smaller kills more frequently. The findings from this study indicate that the white lions survived as successfully as the tawny lions studied.

It is acknowledged that certain factors in the study area may have facilitated the white lions’ hunting conditions by comparison to the conditions during the other lion studies, but the conditions were the same for the Tsau Tawny Lion Group and the hunting success of the aforementioned was comparable with both White Lion Group A and B. Some of the factors that were different in the study area were: the prey species and numbers were controlled; no other large predators and conspecifics were resident in the study area, apart from some transient leopard or spotted hyaena; and the small size of the area may have ensured the presence of prey within a certain proximity. Despite the small size of the rewilding area, the number of fence kills was minimal, and all three lion groups studied made kills randomly across the entire study area (Figures 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3). Subsequent to the completion of this study, White Lion Group A has been released into a larger area where there are large dangerous prey including giraffe and buffalo, and the two male lions were observed killing adult buffalo. Furthermore, in 2010 the adult male lion from White Lion Group B (13 years old) was confronted by a wild tawny male lion (8 years old) that broke through the boundary fence from the neighbouring Kapama Game Reserve, and the white lion male successfully fended him off the intruder. Additionally, in 2014, one of the adult white lionesses in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve defended herself against a rival group of 4 adult lionesses, further signs suggesting that white lions are capable of surviving in the wild in their natural habitat.

There were other factors that may well have made hunting conditions more difficult for the white lion group. The small sized area may have increased the vigilance of prey, thus making stalking and successful hunting more difficult [28]. Moreover, the captive-born white lioness and her offspring (White Lion Group A) were learning to hunt and the lioness in particular had to overcome the negative factors associated with being hand- reared in captive conditions and being the only adult (capable hunter) in the founder group. Although there were two adult lions in White Lion Group B, the male lion was often separate on a territorial patrol, as is typical behaviour for pride males [13]. Additionally, the two introduced groups of white lions were all white and should therefore have been even more conspicuous than the naturally occurring white lions that were integrated in tawny prides. As approximately 30% of the white lion groups’ successful hunts took place during daylight or on moonlit nights, it further strengthens the case. However, as discussed for the lions of MLR [28], some of the daylight and moonlight success may be ascribed to the camouflage provided by the vegetation and/or the presence of the diurnal warthog. Additionally, tall grass, dense vegetation and dark moon conditions have been identified as the most important environmental factors that determined lion hunting success of medium-sized prey, such as blue wildebeest, in the KNP [39]. Because lions hunt mostly at night [13] and most lion prey see poorly at night [48], it is postulated that the white coat colouration in lions is less significant for hunting success than previously perceived. Evidence in support of this hypothesis is the self-sufficient hunting and survival of an adult white lioness in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve in the 1990’s [49]. This lioness was observed hunting and surviving alone after her tawny sister was killed by nomadic male lions, and she successfully raised three litters of cubs. This adult white lioness survived despite the extreme human intervention of snaring, lion trophy hunting, consequent pride disruption and infanticide [49]. Further evidence of the hunting ability of white lions is the occurrence of two adult white lionesses surviving and hunting on their own in the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve in 2015 [50, Patrick O’Brien personal communication]. Additionally, a pride of white lions has been surviving in the wild for more than 5 years at the Pumba Game Reserve in the Eastern Cape of South Africa [Dale Howarth personal communication].

The adaptation of the released white lions to managed free-roaming conditions and their hunting success in the rewilding area gives preliminary evidence that white lions can hunt self-sufficiently, with a kill rate and a food consumption rate that are comparable to wild tawny lions in the same environment and study area. These findings put into question the postulation that white lions cannot hunt successfully in the wild due to a lack of camouflage [8], confirming prediction a that white lions show similar hunting success to other wild lions, and therefore supporting hypothesis a that white lions can survive in the wild. Due to the absence of conclusive scientific study on white lions in their natural habitat, the findings of this study are preliminary, but suggest that further study is necessary.

Conclusions

Having determined that white lions can hunt successfully under managed free-roaming conditions, with a kill rate and a food consumption rate that is comparable to wild tawny lions, we suggest therefore that white lions are capable hunters and are able to survive in their natural habitat. Since white lions occurred in their natural habitat both historically and recent to the writing of this article (1938; 1975 to 1980; 1994; 2006 to 2015), we propose therefore that the disappearance of white lions from the natural ecosystem was not due to an inability to hunt, but instead due to other factors most likely anthropogenic related. To conclusively investigate this postulation, we recommend that the hunting behaviour and ecology of white lions be studied under fully free-roaming conditions.

Acknowledgements

All sponsors of and contributors to the Global White Lion Protection Trust are thanked for their unconditional support. T. Kukkonen and J. Gaugris are thanked for their work on this paper. Gratitude is expressed to the Global White Lion Protection Trust (GWLPT) research team for their dedicated monitoring of the lions and assistance with collection of data. M. Strauss, G. Saayman and L. Tucker are sincerely thanked for their input and support. Thank you to J. & A. Gardy for sponsoring the publication of this article.

Author's contributions

J. T. conceived of the study, coordinated the field research and drafted the manuscript. C. V. assisted with field research and data analysis and helped to draft the initial manuscript. M. J. S. advised on the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Searle, A. G.: Comparative Genetics of Coat Color in Mammals. New York: Academic Press; 1968.

2. Römpler H., Rohland N., Lalueza-Fox C., Willerslev E., Kuznetsova T., Rabede G., Bertranpeti J., Schöneberg T., Hofreiter M.: Nuclear gene indicates coat-colour polymorphism in mammoths. Science 2006, 313(5783): 62.

3. Darwin, C. R.: The Origin of Species. Vol. XI. The Harvard Classics. New York: PF Collier & Son;1909–14.

4. Hoekstra, H. E.: From Darwin to DNA: The Genetic Basis of Colour Variations. In: In the Light of Evolution: Essays from the Laboratory and Field. Edited by Losos, J.: Roberts and Company Publishers; 2010: 277-295.

5. Marshall H. D., Ritland K: Genetic diversity and differentiation of Kermode bear populations. Molecular Ecology 2002: 11(685-697).

6. Kaelin, C. B., Xu X., Hong L. Z. , David V. A., McGowan K. A. et al. Specifying and Sustaining Pigmentation Patterns in Domestic and Wild Cats. Science 2012, 337(6101):1536–1541.

7. Xu et al.: The Genetic Basis of White Tigers, Current Biology 2013, 23: 1-5 in press; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.054.

8. McBride C.: The White Lions of Timbavati. New York: Paddington Press; 1977.

9. McBride, C.: Operation White Lion. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1981.

10. Robinson R., De Vos V.: Chinchilla mutant in the lion. Genetica 1982, 60: 61-63.

11. Tucker L: Mystery of the White Lions: Children of the Sun God. White River: Npenvu Press; 2003.

12. Cruickshank K. M., Robinson T. J.: Inheritance of the white coat colour phenotype in African lions (Panthera leo). In: Proceedings of a Symposium on Lions and Leopards as Game Ranch Animals. Edited by Van Heerden J. Onderstepoort: Wildlife Group of the South African Veterinary Association; 1977.

13. Smuts G. L.: Lion. Johannesburg: MacMillan South Africa; 1982.

14. Cadman M.: First wild white lions born in Timbavati area for 12 years. In: The Sunday Independent 2006, 26: 1.

15. Van Dyk G.: Reintroduction techniques for lion (Panthera leo). In: Proceedings of a Symposium on Lions and Leopards as Game Ranch Animals. Edited by Van Heerden J. Onderstepoort: Wildlife Group of the South African Veterinary Association; 1997.

16. Miller B., Ralls K., Reading R. P., Scott J. M., Estes J.: Biological and technical considerations of carnivore translocation: a review. Animal Conservation 1999, 2: 59-68.

17. Jule K. R , Leaver L. A., Lea S. E. G.: The effects of captive experience in reintroduction survival in carnivores: a review and analysis. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141(2): 355-363.

18. Griffith B., Scott J. M., Carpenter J. W., Reed C.: Translocation as a species conservation tool: status and strategy. Science 1989, 345: 447–480.

19. Snyder N. F. R., Derrickson S. R., Beissinger S. R., Wiley J. W., Smith T. B., Toone W. D., Miller B.: Limitations of captive breeding in endangered species recovery. Conservation Biology 1996, 10: 338-348.

20. Stuart S. N.: Re-introductions: to what extent are they needed? Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 1991, 62: 27-37.

21. Stanley Price M. R.: A review of mammal re-introductions, and the role of the Re-introduction Specialist Group of IUCN/SSC. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 1991, 62: 9-25.

22. Moore D. E., Smith R.: The red wolf as a model for carnivore re-introductions. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 1990, 62: 263-278.

23. Linnell J. D. C., Aanes R., Swenson J. E., Odden J., Smith M. E.: Translocation of carnivores as a method for managing problem animals: a review. Biodiversity and Conservation 1997, 6: 1245-1257.

24. Brocke R. H., Gustafson K. A., Major A. R.: Restoration of lynx in New York: biopolitical lessons. Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 1990, 55: 590-598.

25. Mucina L., Rutherford M. C. (Ed): The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland. Strelitzia Volume 19. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2006.

26. IUCN: IUCN guidelines for reintroduction. Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Reintroduction Specialist Group; 1998.

27. Turner J,: The impact of lion predation on the large ungulates of the Associated Private Nature Reserves, South Africa. MSc thesis. University of Pretoria, Centre for Wildlife Management; 2005.

28. Power R. J.: Prey selection of lions Panthera leo in a small, enclosed reserve. Koedoe, 2002, 45: 67-75.

29. Bertram, B. C. R.: Weights and measures of lions. East African Wildlife Journal, 1975, 13: 141 – 143.

30. Hayward M. W., Kerley G. I. H.: Prey preferences of the lion (Panthera leo). Journal of Zoology 2005, 267: 309-322.

31. Hooge, P.N. 1999. Animal movement analysis Arcview Extension, USGS-BRD, Alaska Biological Science Centre, Glacier Bay Field Station, Gustavus.

32. Jacobs J.: Quantitative measurement of food selection - a modification of the forage ratio and Ivlev's electivity index. Oecologia 1974, 14:413-417.

33. Van Orsdol, K.G. 1982. Ranges and food habits of lions in Rwenzori National Park, Uganda. Symp. Zool. Soc. Lond. 49: 325–340.

34. Kilian P. J.: The ecology of reintroduced lions on the Welgevonden Private Game Reserve, Waterberg. MSc thesis. University of Pretoria, Centre for Wildlife Management; 2003.

35. Lehmann M. B., Funston P. J., Owen C. R., Slotow R.: Feeding behaviour of lions (Panthera leo) on a small reserve. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 2008, 38: 66-78.

36. Palomares F., Delibes M., Revilla E., Calzada J., Fedriani J. M.: Spatial ecology of the Iberian lynx and abundance of European Rabbit in southwestern Spain. Wildlife Monographs 2001,148, 1-36.

37. Dunn O. J.: Technometrics 1964, 5: 241 - 252

38. Frankham R: Conservation genetics. Annual Review of Genetics 1995, 29:305-327.

39. Mills M. G. L., Biggs, H. C.: Prey apportionment and related ecological relationships between large carnivores in Kruger National Park. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 1993, 65: 253 – 268.

40. Schaller, G. B.: The Serengeti Lion: A Study of Predator–Prey Relations, University of Chicago Press, Chicago; 1972.

41. Rudnai, J.: The pattern of lion predation in Nairobi Park. East African Wildlife Journal, 1974, 12: 213–225.

42. Druce D., Genis H., Greatwood S., Delsink A., Hunter L., Slotow R., Braak J., Kettles R.: Prey selection by a reintroduced lion population in the Greater Makalali Conservancy, South Africa. African Zoology 2004, 39: 273-284.

43. Hunter L. T. B.: The behavioural ecology of reintroduced lions and cheetahs in the Phinda resource reserve, Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. PhD thesis. University of Pretoria, Mammal Research Institute; 1998.

44. Bothma J. du P., Walker C. H.: Larger carnivores of the African savannas. Pretoria: J. L. van Schaik Publishers; 1999.

45. Funston P. J.: Predator-prey relationships between lions and large ungulates in the Kruger National Park. PhD thesis. University of Pretoria, Mammal Research Institute; 1999.

46. Carr N.: Return to the Wild: A story of two lions. St James’ Place: Collins Publishers; 1962.

47. Skinner J. D., Chimimba C. T.: The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cape Town: Cambrige University Press; 2005.

48. Goldsmith T. H.: What birds see. Scientific American 2006, 295: 68–75.

49. Cesare M.: Man-eaters, Mambas and Marula Madness: A Game Ranger’s Life in the Lowveld. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishing; 2011.

50. The White Lions

Cite this paper

APA

Turner, J. A., Vasicek, C. A., & Somers, M. J. (2015). Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa. Open Science Repository Biology, Online(open-access), e45011830. doi:10.7392/openaccess.45011830

MLA

Turner, Jason A., Caroline A. Vasicek, and Michael J. Somers. “Effects of a Colour Variant on Hunting Ability: The White Lion in South Africa.” Open Science Repository Biology Online.open-access (2015): e45011830. Web. 8 May 2015.

Chicago

Turner, Jason A., Caroline A. Vasicek, and Michael J. Somers. “Effects of a Colour Variant on Hunting Ability: The White Lion in South Africa.” Open Science Repository Biology Online, no. open-access (May 08, 2015): e45011830. doi:10.7392/openaccess.45011830.

Harvard

Turner, J.A., Vasicek, C.A. & Somers, M.J., 2015. Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa. Open Science Repository Biology, Online(open-access), p.e45011830. Available at: http://www.open-science-repository.com/biology-45011830.html.

Science

1. J. A. Turner, C. A. Vasicek, M. J. Somers, Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa, Open Sci. Repos. Biol. Online, e45011830 (2015).

Nature

1. Turner, J. A., Vasicek, C. A. & Somers, M. J. Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa. Open Sci. Repos. Biol. Online, e45011830 (2015).

doi

Research registered in the DOI resolution system as: 10.7392/openaccess.45011830.

Open reviews for this paper

Click below to see contributions from reviewers of this page.

Review of the research report: “Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa” Not rated yet

Review of the research report:

“Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa”

by

Graham S. Saayman, Ph.D. (Canada/South …

Review of the article "Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa" Not rated yet

In their article “Effects of a colour variant on hunting ability: the white lion in South Africa”, the Authors, Jason Turner, Caroline Vasicek, and Michael …

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.